Facts, Fear, Hype: How Hormone Therapy for Menopause Got So Complicated

Few treatments have inspired as much hope — or alarm. Learn about the evolving conversation around hormone therapy.

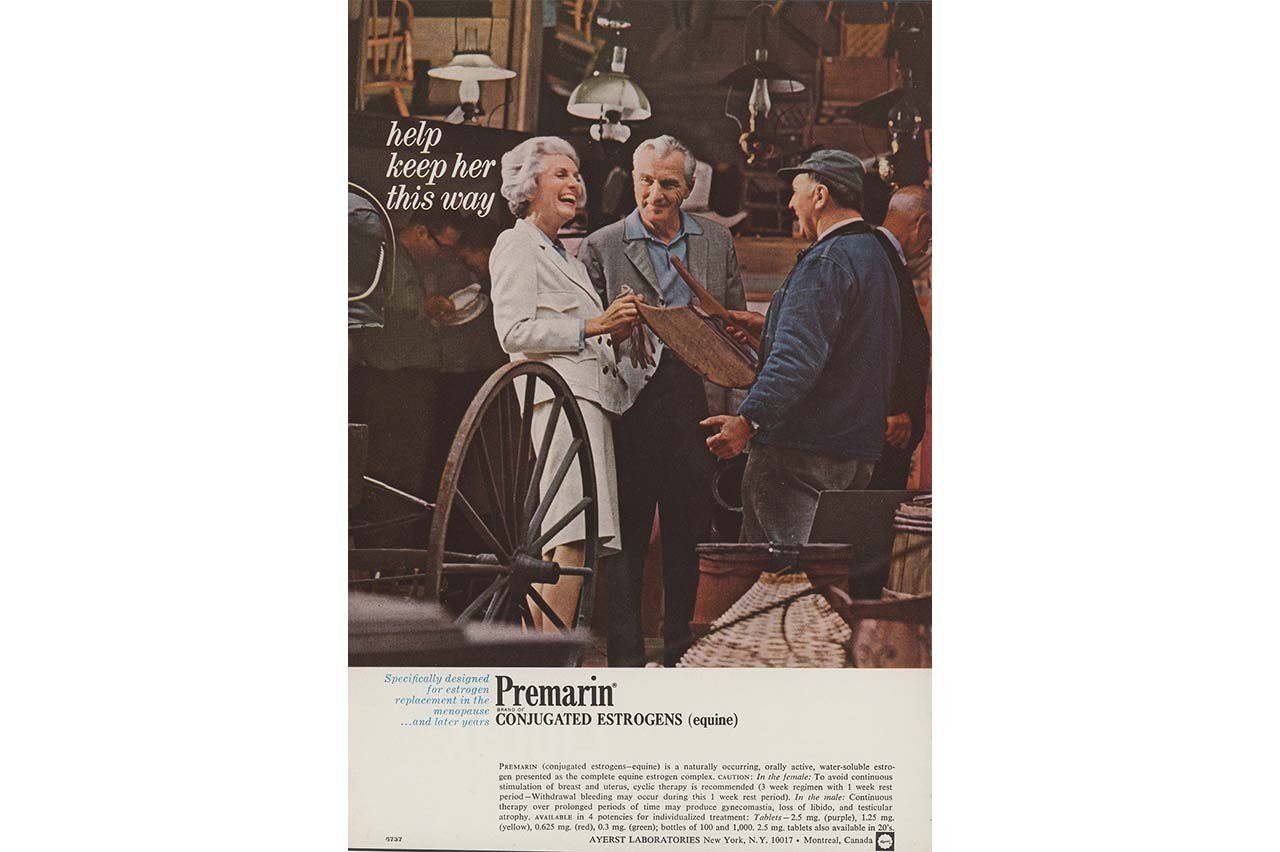

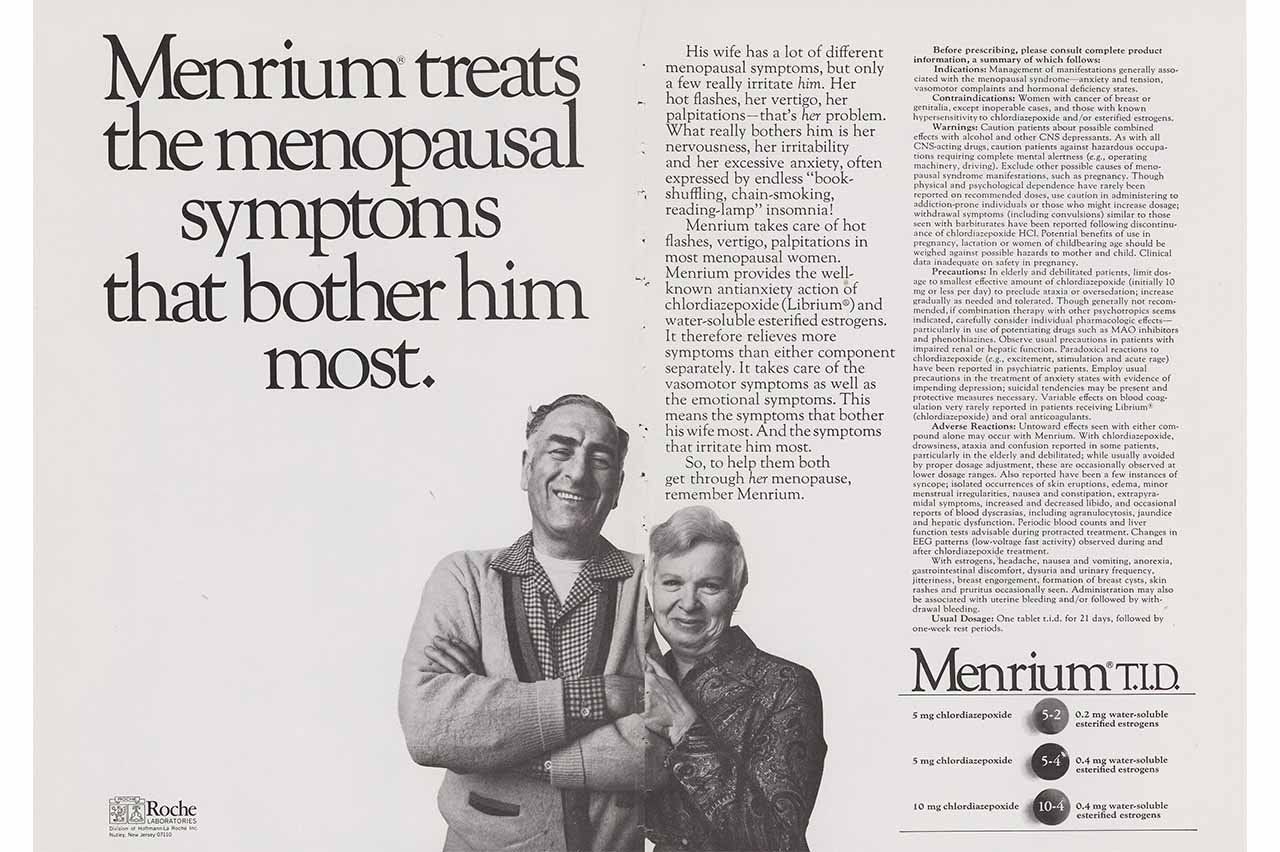

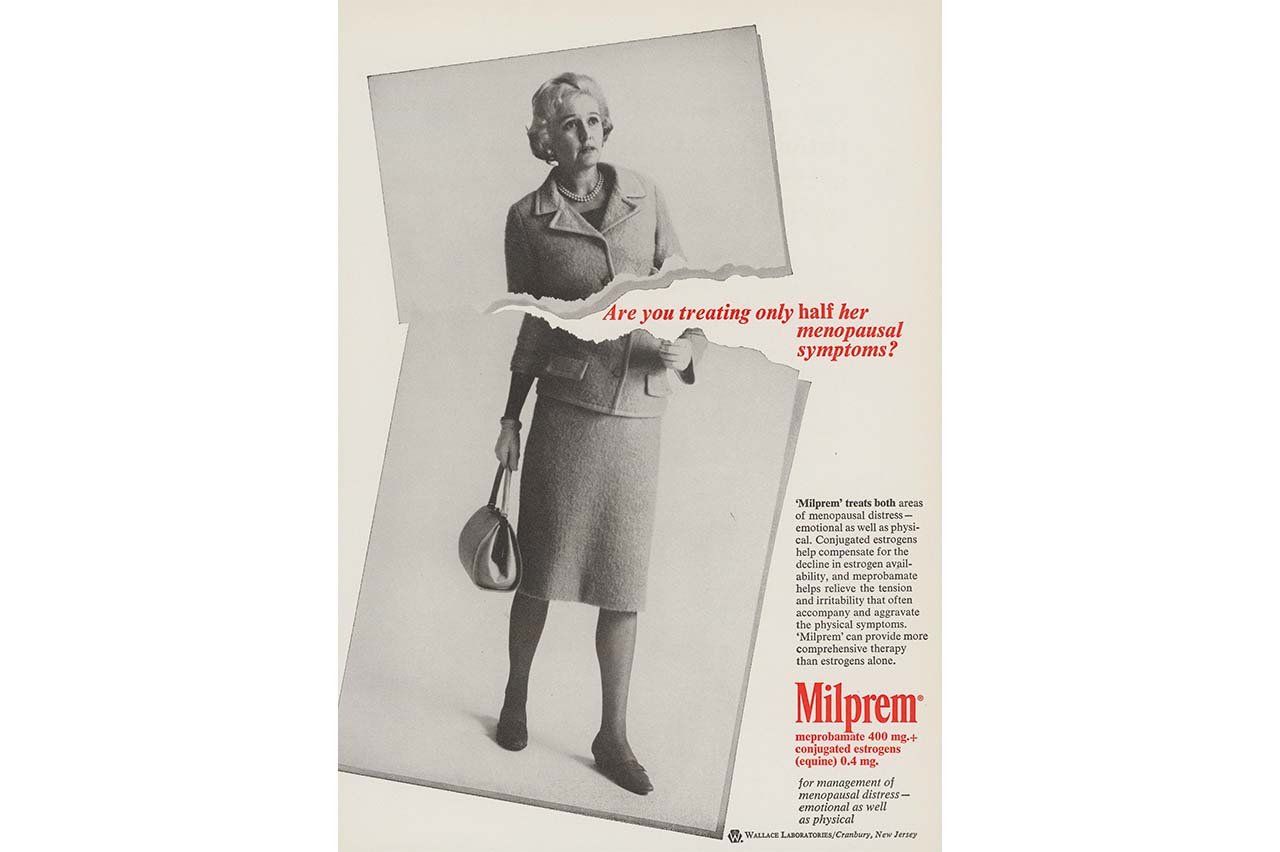

The marketing for hormone therapy has come a long way. In the 1960s, ads for Premarin — pills containing equine estrogens derived from the urine of pregnant horses — were actually targeted to men, drumming up demand by suggesting that menopause made their wives less pleasant and pretty: “Help keep her this way.”

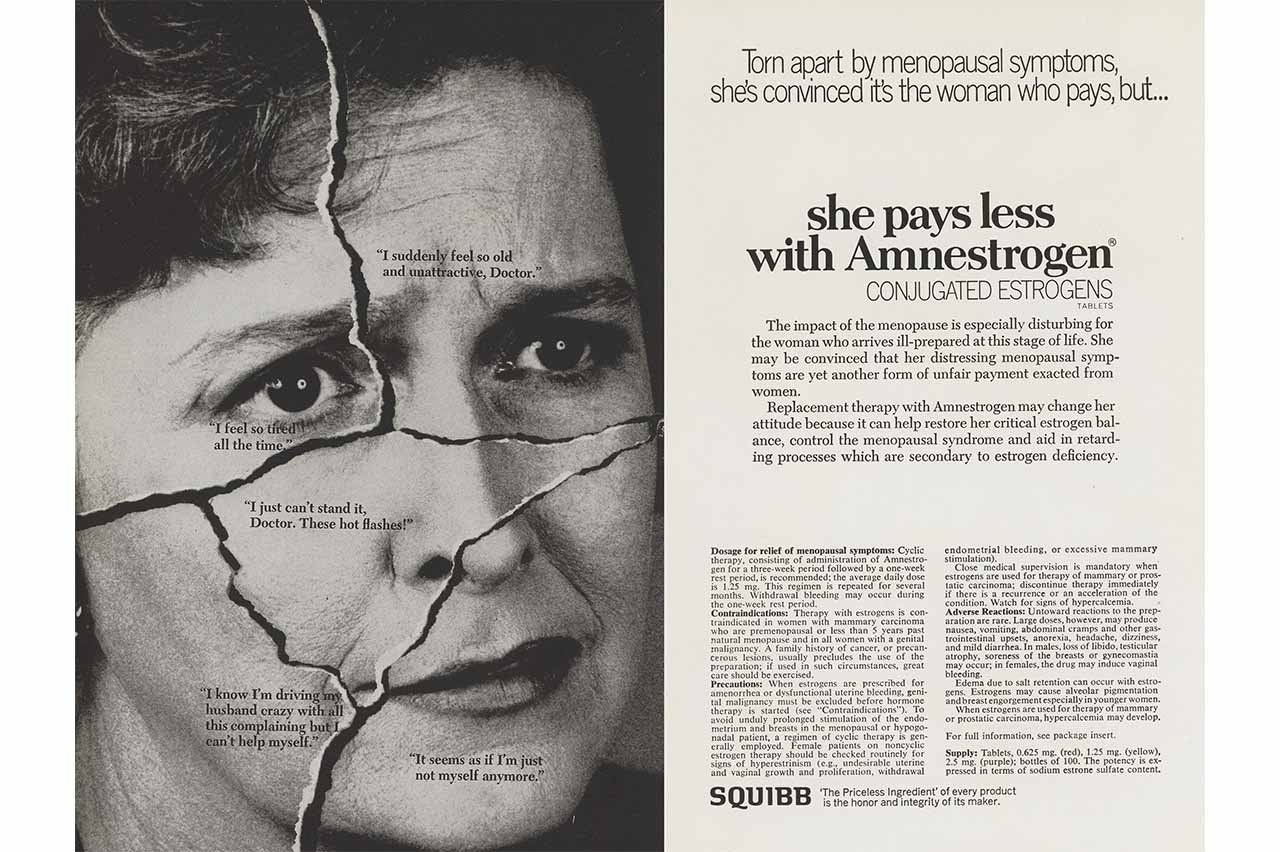

Today, most women make their own medical decisions. Recent ads, many of them produced by pharmacies and a growing crop of online health providers, focus on overcoming symptoms, which can range from night sweats to vaginal dryness. “Sweaty? Tired? Moody? Over it.” “Menopause is hot. Nothing is sexier than being in control.” The ads are meeting an audience of middle-aged women hungry for advice about whether hormone therapy might fix what ails them.

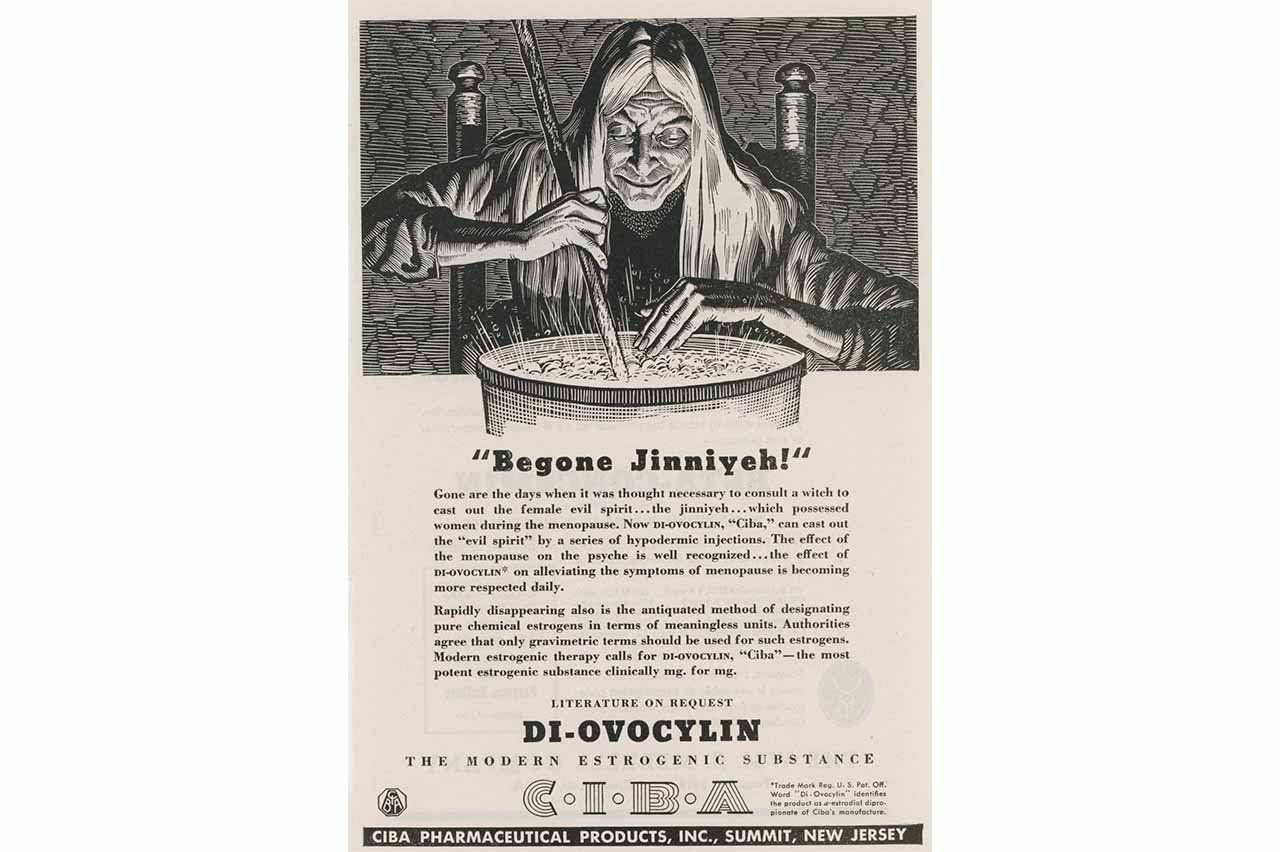

Hormone Therapy Ads, 1938-1971

Hormone therapy ad, 1967-1969. Source: University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries, Health Advertisements Database from Ebling Sources (HADES)

Hormone therapy ad, 1967-1969. Source: University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries, Health Advertisements Database from Ebling Sources (HADES)

Hormone therapy ad, 1938-1943. Source: University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries, Health Advertisements Database from Ebling Sources (HADES)

Hormone therapy ad, 1970-1971. Source: University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries, Health Advertisements Database from Ebling Sources (HADES)

Hormone therapy ad, 1964-1966. Source: University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries, Health Advertisements Database from Ebling Sources (HADES)

For many years, messages about the merits and risks of hormone therapies have puzzled patients. In the 1990s, Premarin was among the most prescribed medications in the U.S. Hormone therapy was hailed for its proven ability to prevent bone loss and its debated potential to lower the risk of heart disease and to preserve memory. The narrative shifted suddenly in 2002, when the Women’s Health Initiative, a clinical trial monitoring the long-term effects of hormone therapy, found that older women taking Premarin had twice the risk of dementia compared to those taking a placebo. The researchers also identified an increased risk of endometrial and breast cancer, blood clots, and stroke in women taking Premarin.

Many women came to fear hormone therapy. And a lot of physicians refused to prescribe it, even for patients with overwhelming symptoms. Unfortunately, these women often didn’t have great alternatives. For example, some antidepressants can reduce hot flashes and night sweats, but they’re not the gold standard for symptom relief.

professor of medicine

“Women with severe hot flashes — what’s most likely to relieve them?” asks Alison Huang, MD ’02, a UCSF primary care doctor and professor of medicine whose research focuses on conditions related to menopause and aging. “Hormone therapy. That’s it.”

Over the last two decades, some researchers have argued that the extreme caution resulting from the Women’s Health Initiative was an overreaction. The average participant was 63 at the start of the study, a decade past the average age of menopause; advocates for hormone therapy believe it carries fewer risks if started when women are in their 40s or 50s. And further study suggests that modern hormone therapy protocols, which use transdermal estradiol instead of Premarin, are safe for most women under 60. In November, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) decided to remove the black box warning on most forms of menopausal hormone therapy.

Now, Huang worries that the consensus on hormone therapy might be shifting again — essentially from “bad” to “good” — when the reality varies from one patient to the next. And for some, particularly women with estrogen-sensitive cancers or a history of stroke, systemic hormone therapy is almost never recommended. The risks seem to outweigh any possible benefits.

Progress toward better alternative treatments for menopause symptoms has been slow, but some new options are emerging. In October, the FDA approved Lynkuet, a medication for hot flashes and night sweats that works on receptors in the brain related to temperature and sleep.

“There is an urgent need for more research on the health of older women,” says Huang, who is the director of the UCSF Women’s Health Clinical Research Center. “Estrogen intersects with virtually every body system or process in some way. But that doesn’t mean giving estrogen will improve all the health outcomes we care about.

“Hormone therapy is not a panacea. It has benefits and downsides. At the end of the day, it’s just a medication like any other.”