Jonas wears the close-shaved natural hairstyle that’s on-trend for many Black men. He’s been styling his hair this way for years, but during the pandemic he noticed, a few days after each shave, some spots on his scalp that hurt or even bled a little. When the pain and bleeding started to spread, he searched for Black dermatologists and found Jenna Lester, MD. “I wanted someone that had familiarity with my skin,” he says.

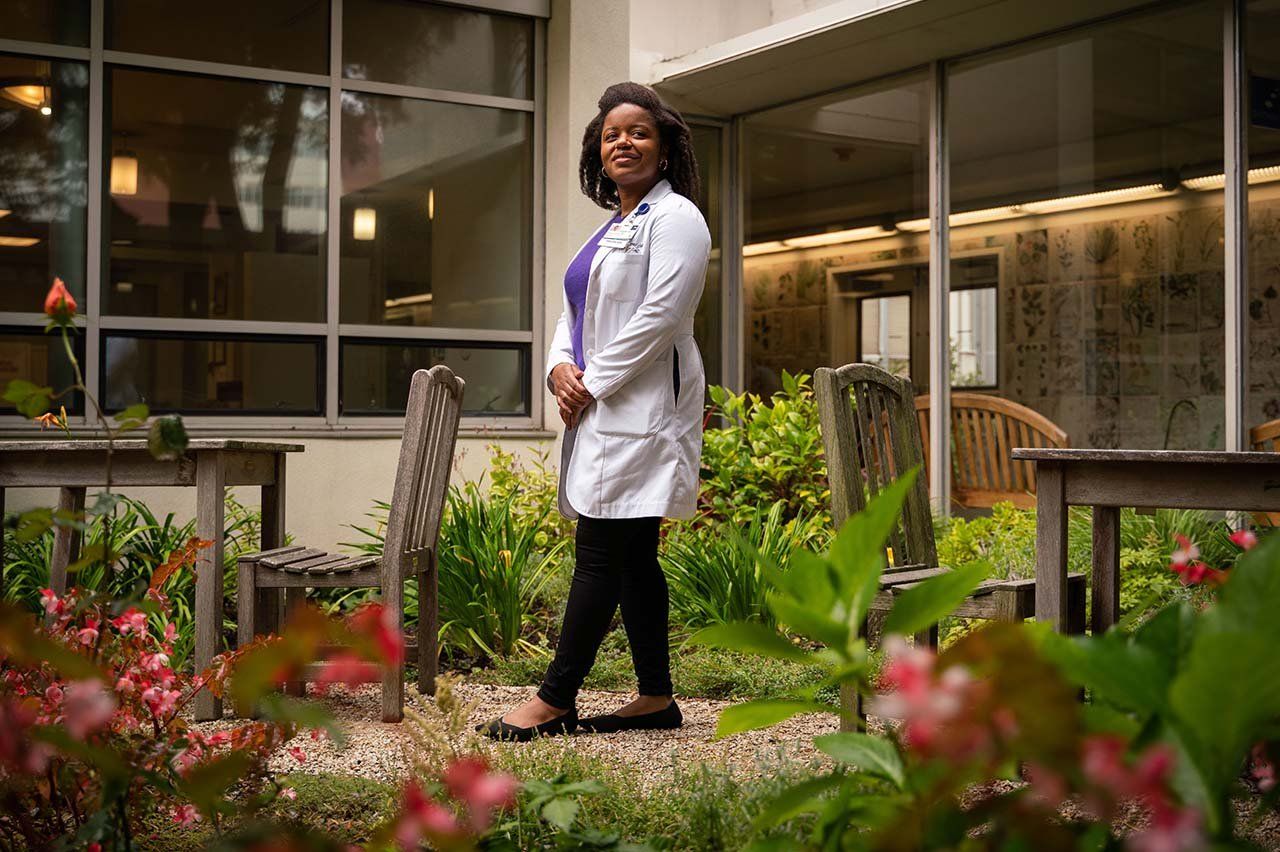

Lester directs the Skin of Color Program at UC San Francisco, which includes a training clinic that specializes in treating dark skin. There are just a handful of such clinics across the country, and Lester’s is the only one in Northern California.

Sporting pink glasses, black Nikes, and a white lab coat, Lester greets Jonas with the warmth of an old friend. She listens to his concerns and then asks a series of detailed questions: What kind of razor do you use? Any creams or lotions? How about aftershave? When you shower, what kind of soap do you use? Do you have a rash anywhere else? What have you tried to resolve this?

Soon enough, she determines the cause of his ailment: Pseudofolliculitis barbae. Also known as ingrown hairs or razor bumps, the condition is especially prevalent in Black people. “We have curly hair,” Lester explains to Jonas, “and so our hair can lose its way as it’s about to erupt out of the skin,” leading to inflammation. She swabs his scalp for a lab test and recommends a treatment plan that includes washing his head and then applying benzoyl peroxide, an antiseptic. If that doesn’t help, she tells him, he might have to consider giving himself a less close shave in the future.

People of color often seek out specialists like Lester because they’ve been misdiagnosed in the past or suspect their doctors are missing something. They’re right to be skeptical. In a survey of U.S. dermatologists, nearly half said their training left them feeling unqualified to diagnose disease in Black or brown skin.

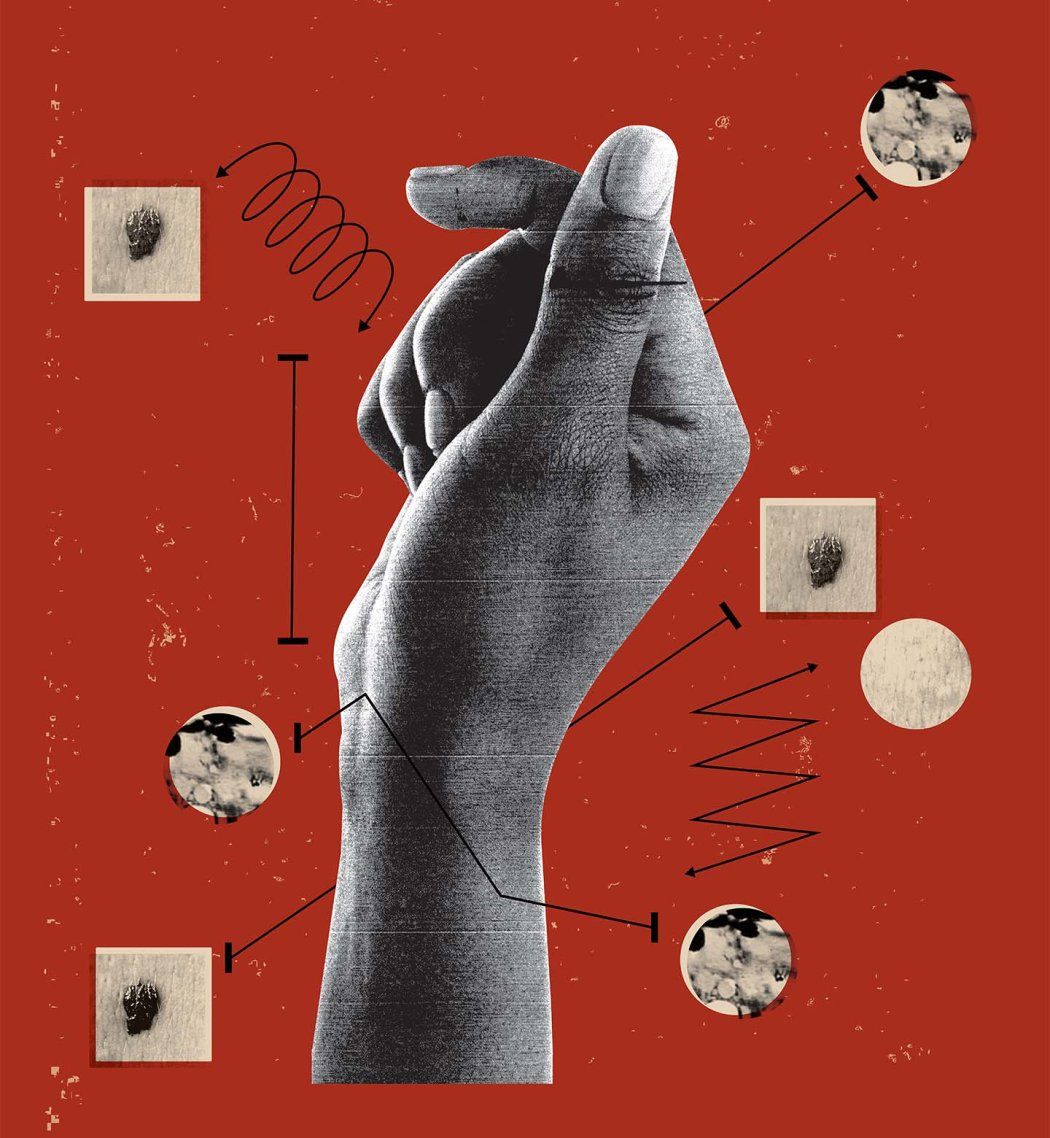

Some skin conditions show up on different parts of the body or look different on light and dark skin. White people, for instance, tend to develop melanoma on their chest, face, or back. For Black people, melanoma often first appears on their palms or the soles of their feet or as a dark stripe down a fingernail. Other examples include psoriasis, dermatitis, and COVID-19 rashes, which look pink or red on light skin but can be purple or brownish on dark skin.

COVID rashes look purple or brownish on dark skin and pink or red on light skin. Photos: Science Source; Dr P. Marazzi/Science Source

Melanoma often appears on the chest, face, or back of people with light skin and on the feet, hands, or fingernails of people with dark skin. Photos: National Cancer Institute/Science Source; © VisualDx/Charles E. Crutchfield III MD

Lester recalls an incident during her training when a Black patient sat in the emergency room for hours because no one knew what to make of the person’s peeling, blistering skin. The ultimate diagnosis was toxic epidermal necrolysis, a life-threatening disorder that can result from a drug reaction. On white skin, one of its hallmarks is redness, but the coloration can be more subtle on darker skin. “You have to train your eye to see things in all skin tones,” she says.

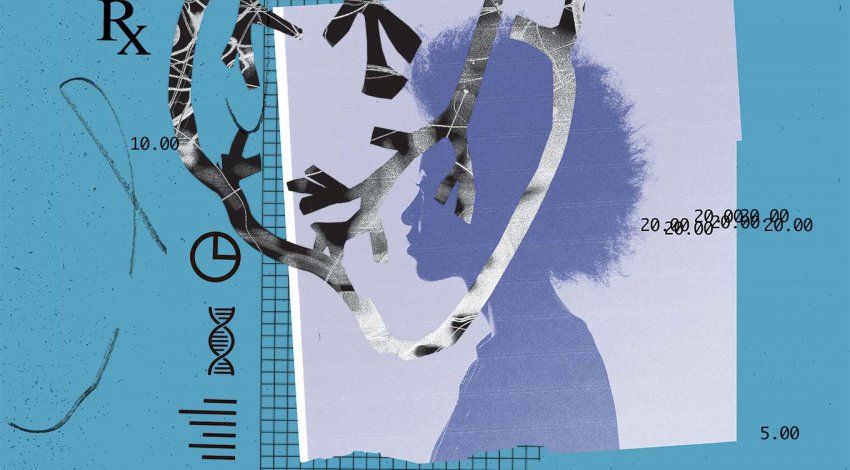

Unfortunately, most medical students and dermatology residents rarely see examples of dark-skinned people in their curricula. When Canadian researchers analyzed more than 4,000 pictures in mainstream medical textbooks, they found that 74.5% of the images showed light skin, 21% showed medium skin, and just 4.5% showed dark skin. Lester recently reviewed 130 images of COVID rashes published in academic journals and found they too were overwhelmingly of light skin, even though the coronavirus has disproportionately sickened people of color.

But, as Lester noted in a widely viewed TED talk and in a paper in the British Journal of Dermatology, one of the only contexts in which dark-skinned people appear regularly is in chapters on sexually transmitted infections. “What does this do to impressionable learners?” Lester asks in her 2021 TED talk on the subject. “Does it make them think that someone with dark skin is more likely to have a sexually transmitted infection?”

Inadequate training also intersects with myths about Black people that pervade American popular culture. For instance, the saying “Black don’t crack” is a nod to the observation that Black people often look much younger than white people the same age. Some think that’s because Black skin is thicker or oilier than white skin. But that’s not the case, Lester says. The likely reason, she explains, is the fact that Black people have more melanin, the substance that gives skin its color, and it acts as a natural sunscreen and prevents some skin damage.

Other myths aren’t so benign – like the misconception that dark-skinned people don’t get skin cancer. Black and Latinx people are less likely than white people to get melanoma (and other skin cancers). But they’re much more likely to die from it. One reason is delayed treatment, Lester says. Studies show that patients of color receive fewer referrals to specialists and endure longer waits for follow-up visits than their white counterparts. While some providers may discriminate outright, others don’t recognize early signs of cancer on dark skin or don’t think to look for it or to warn their patients about risk factors. “It’s dangerous when our lay thoughts encroach on our clinical decisions,” Lester says.

She sees it as part of her mission to educate her dermatology colleagues, the vast majority of whom are white, about how to spot conditions on dark skin and how to ask questions to make culturally aware diagnoses. Black people make up 14% of the U.S. population but only 3% of dermatologists, and similar gaps exist for Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous groups. At a recent conference, Lester told the story of a Black patient whose previous dermatologist had recommended daily hair washing to help with scalp irritation and dandruff. That may be sound advice for some people, but, Lester jokingly informed her audience, it’s the “fastest way to lose credibility with a Black woman.” She explained that frequent hair-washing can dry out the hair and lead to damage or breakage in Black patients.

And many Black women suffer from alopecia, or hair loss, which can result from techniques used to achieve hairstyles that reinforce Eurocentric standards of beauty. So Lester also encouraged her colleagues at the conference to ask their senators to support the CROWN Act, which bars discrimination against people with braids, Afros, and other natural hair styles. “I’m not sure they were expecting that,” Lester says. “But I’m here to make a difference.”

As a doctor, Lester is following a path set by her mother, a geriatrician, and her grandmother, one of New York’s first Black nurse practitioners. Initially, she thought primary care would give her the best opportunity to combat the inequities in medicine that have led to poorer outcomes for Black patients. “I am a person who is tired of oppressive systems,” she says. But she decided to pursue dermatology after an internship with veterans showed her that access to high-quality skin care was sorely needed. “Jenna is an idealist,” says Nina Botto, MD, a fellow UCSF dermatologist. “She wants the world to be right and people to have the care that they need and deserve – and not just the people that are in the textbooks.”

Lester is proud to follow in the footsteps of pioneering Black dermatologists such as Susan Taylor, MD, at the University of Pennsylvania. Taylor opened the nation’s first skin of color clinic in New York in 1998 and created the Skin of Color Society to promote dermatology research and education focused on patients with dark skin. “There’s an accomplished group of Black dermatologists who paved the way for me to do the work I’m doing now,” Lester says.

Now she herself is a mentor to a new generation of dermatology residents, who rotate in her clinic once a week. Besides teaching them practical skills for treating dark skin, Lester hopes to impart the knowledge and cultural sensitivity they’ll need to care effectively for their patients of color – which includes understanding the importance of advocating for patients and making them feel valued and respected. “When patients have been excluded from a health care environment for so long,” she says, “showing them that they are welcome and their concerns will be addressed is critical.”