A hard-working doctor at San Francisco General Hospital could be forgiven for overlooking a nearby watering hole known as the Homestead. With peanut shells on the floor and tastefully ironic boudoir paintings on the walls, the place could well be yet another Mission District hipster hole-in-the-wall.

But the Homestead is more than just a spot for bearded 20-somethings (and their omnipresent dogs) to unwind with their friends. In fact, the Homestead is the birthplace of UC San Francisco’s Institute for Global Orthopaedics and Traumatology (IGOT), a small, innovative program with big, worldwide intentions. Sure, IGOT has a proper home in an elegant brick building at the hospital – a UCSF partner – but its heart and soul reside in Thursday afternoon sessions at the Homestead, where a handful of professionals conceived of the program eight years ago.

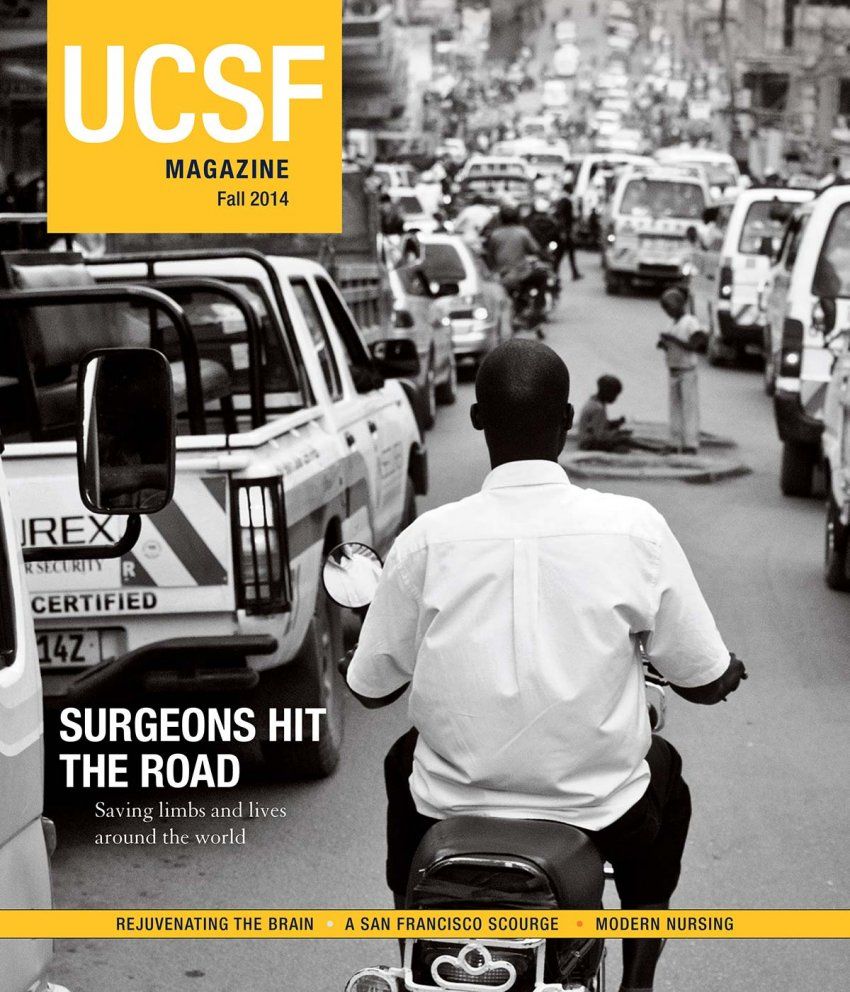

To understand the impetus behind IGOT is to confront some shocking statistics. Almost 6 million people worldwide die from traumatic injuries every year. That’s more than are killed by HIV/AIDS, malaria and TB combined. A quarter of those injuries result from traffic accidents, which far outstrip injuries from violence, war, suicide, or any other cause. By some counts, a quarter of all hospital beds in the world are occupied by victims of traffic accidents. The vast majority of those patients live in the developing world; in fact, the World Health Organization estimates that such countries lose up to 3 percent of their GDPs as a result of traffic accidents.

“The good news,” says Richard Coughlin, MD, one of IGOT’s founders, “is that we know how to fix these injuries. People in Tanzania have the same number of bones as people in San Francisco, and they fit together in the same way.” What’s different – apart from the sheer number of injuries – is the medical and cultural setting in which they are treated. Specifically, in the developing world, amputation is often the go-to solution for compound fractures and complicated soft tissue injuries.

Richard Coughlin started the program after seeing the impact of trauma in Central America and South Africa.

“Amputation is culturally, functionally, socially, and economically horrible,” explains Coughlin, a professor of orthopaedic surgery at UCSF. “It affects not only the 25-year-old who mangles his leg, but also his entire family, clan, and village, who have to take care of him.” In the developed world, amputation is relatively rare, and those who must undergo it have access to physical therapists, advanced prostheses, engineering expertise, and legal remedies that make the world still navigable.

When UCSF orthopaedic surgery resident Amanda Whitaker, MD, traveled to mountainous Nepal, she noted that “the only way for a nonambulatory child to even get to a hospital is to be carried. And what happens when he gets too big to ride on his parents’ backs?” In addition, social stigma against those with disabilities often rules out marriage for them, and people with orthopaedic traumas usually go from being breadwinners to burdens.

Devastating Effects

Coughlin first saw the devastating effects of trauma in the developing world in the 1990s, when he traveled to South Africa and Central America. “It kind of hit me,” he says. “I started thinking it would be great for residents to have this experience. I wanted it to be a true rotation, not just coming over for a quick operation, smiles all around.”

Moreover, Coughlin and his colleagues recognized that preventing amputations wasn’t about access merely to Western doctors, but also to the techniques they practiced. And so, over a series of conversations and beers at the Homestead, an idea took shape. Not only would this new program bring American medical students to the developing world, but doctors from those countries would come to the United States to learn surgical techniques that they could implement – and teach to colleagues – back home. In this way, the relatively small number of orthopods at UCSF would become force multipliers in the global fight against traumatic injuries.

Victims of traffic accidents occupy a quarter of all hospital beds in the world by some estimates. Photo: Amber Caldwell

True to Coughlin’s dream, the international component is now a full and rigorous rotation, not just an adventure in medical tourism. UCSF orthopaedic residents can travel to one of five countries – Tanzania, Ghana, Malawi, Nicaragua, or Nepal – and spend four weeks working at a local hospital. In addition to performing surgeries and training local doctors, the residents are exposed to cases and conditions that they wouldn’t normally see in the United States.

“One thing that drew me to UCSF was the opportunity for global involvement,” says Whitaker, who was IGOT’s first resident to travel to Nepal. “For me, it was an eye-opening experience. I saw young adults with untreated clubfoot that would be treated [in the U.S.] right when a child is born. By approximately six months of age, that child could be out of the cast and wearing special shoes. But in Nepal, a family might be unaware of treatment options or have no access to them. And so you see children 8, 9, 10 years old coming in with bad deformities who may have their potential limited by their condition.”

Amanda Whitaker treated children with clubfoot in Nepal as part of her residency.

While other medical schools now offer international rotations for orthopaedic residents, UCSF’s program was the first and is still the most developed. For young doctors like Whitaker, IGOT is a powerful recruiting tool, drawing top-notch talent away from other prestigious medical schools such as Stanford and Harvard.

Today, 75 percent of UCSF’s orthopaedic residents choose to participate in the international rotation.

And that participation has lasting effects. A study published in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery found that “participants were more likely than nonparticipants to believe that physicians have an obligation to the medically underserved.” When compared with their peers at other residencies, IGOT participants were not only more likely to work internationally after completing their training, but also more than twice as likely to volunteer domestically.

“There’s a lot of gratification knowing that we can attract the best young minds to a highly sought-after specialty, and then add the values of humanity and social awareness,” says Coughlin. “Our residents want to make a difference, not just make money.”

Summit Successes

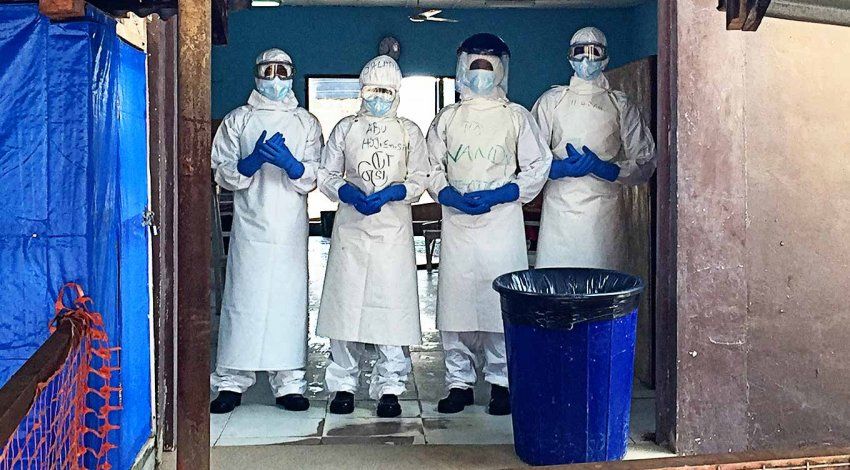

But at the end of the day, some of IGOT’s most important students aren’t UCSF residents at all. Instead, they’re the local orthopaedic surgeons in such far-flung locations as Mthatha, South Africa, and Kabul, Afghanistan. Each year since 2009, IGOT has hosted an international summit, during which more than 60 doctors from dozens of developing countries descend on UCSF for hands-on training.

“Even with all hands on deck, it’s barely controlled chaos,” says Amber Caldwell, the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery’s director of outreach development. All 12 orthopaedic surgeons participate, as well as additional surgeons from general, plastic, podiatric, and vascular surgery. Most of the “students” pay their own way, and though they’re often making their first trip to the United States, sightseeing takes a back seat to learning. “They’re in the lab from 7:00 until 7:00,” says Caldwell. “We pack as much information as possible into those three days, so there’s not much downtime.”

In particular, UCSF surgeons teach a plastic surgery technique known as a rotational flap that helps save limbs. “The real problem,” according to Coughlin, “isn’t fixing fractures. These guys are very good bone doctors. But the soft-tissue part is something they don’t have as much experience with.” With a compound fracture, “it’s the soft tissue around the injury that ultimately dictates functional outcome.” In the developing world, doctors often move straight to amputation rather than risk infection in the traumatized tissue.

Instead, using cadavers and simulation labs, the UCSF surgeons teach their foreign counterparts how to take muscle from a nearby, unaffected part of the body and redirect it where new tissue is needed. This “flap” generally remains attached to its initial location, so it comes with its own viable blood supply. If that’s not possible, a distant piece of tissue can be transferred and revascularized. These techniques are low-tech, low-risk, and relatively easily taught. Furthermore, the solution for a failed flap is amputation, no worse than what a patient would have faced in the absence of the flap procedure.

There is clear evidence that IGOT’s training has been successful. And beyond hundreds of amputations, inestimable pain, suffering, and economic woe have been prevented.

Show on the Road

After the success of the first few training summits in San Francisco, Coughlin realized that “we needed to take this show on the road.” Some of the Tanzanian doctors said that they’d like to see the course taught not just in San Francisco, but also back home. “And they’re right,” says Coughlin. “That’s where it needs to happen. If we can make them the center of excellence for East Africa, we can explode the capacity.” Last year, Coughlin and his colleagues brought their course to Dar es Salaam, where American and African surgeons worked together, teaching surgical techniques to 123 doctors from all across East Africa.

More than 60 doctors from developing countries attend the IGOT training at UCSF each year. Photo: Amber Caldwell

One of the doctors helping to spread the knowledge is Edmund Eliezer, MD, an orthopaedic surgeon at the Muhimbili Orthopaedic Institute in Tanzania. “Our country is full of motorcycles,” he says, “often ridden very fast by riders with no experience. And so injuries are very severe.” Prior to attending IGOT training in San Francisco, Eliezer performed many more amputations than he wanted to. “With all of that exposed bone, we saw too much uncontrolled infection. But with flap surgery, we cover the bone, we prevent the infection, and we save the limb. Improved outcomes have been dramatic.”

Saam Morshed trained surgeons from across East Africa during the course in Tanzania.

Saam Morshed, MD ’01, MPH, PhD, an assistant professor of orthopaedic surgery, traveled to Tanzania with IGOT and was struck both by the patients he encountered and by the skill with which Eliezer and his colleagues treated them. “I saw a 22-year-old kid who’d had a motorcycle accident resulting in a broken femur on one side and a hip fracture plus dislocation on the other,” Morshed recalls. The patient had been sitting in traction since the accident, with one leg five centimeters shorter than the other.

Eliezer very much wanted to learn how to fix this type of posterior wall acetabular fracture. “I was happy to teach him,” says Morshed, who is also a resident alumnus of UCSF. “But I usually deal with this [kind of] injury six hours after the accident, not six weeks.” Nonetheless, the two scrubbed in together and successfully reduced the hip and repaired the posterior wall. A year later, not only had the patient recovered from that injury, but Eliezer was performing similar surgery regularly.

“Now he’s doing more of those than I am,” says Morshed. “Probably more than anybody in North America. I have no doubt that Edmund will be one of the leading pelvic and acetabular surgeons in Africa. He’s going to train and empower generations of doctors to treat people they used to think couldn’t be treated.”

Back at the Homestead

One recent afternoon, Coughlin popped open a Diet Coke and slouched down in his chair at IGOT’s offices in San Francisco. Thursday evenings are usually devoted to “research” at the Homestead, but this day’s surgeries were running long and Coughlin wouldn’t make it there. (Fortunately, the crowd at the Homestead soldiered on without him; owner Raub Shapiro donates a portion of happy hour sales and backroom party rentals to IGOT.)

The homestead, the gathering spot where it all began, donates to the IGOT program. Photo: Eight Hour Day

After taking a call from the OR, Coughlin mused about what his program had accomplished. “To me, this is the pureness of being an orthopod, unburdened by paperwork and policies, just being able to alleviate suffering with my hands. Global road trauma is an atrocity every bit as bad as what we’re seeing in Syria and other war zones. But what we’re doing isn’t the Mother Teresa concept of simply handing out aid. We are global academic partners.”

Morshed, for his part, explains that he just got back from a stay in Dar es Salaam. There, he says, at the intersection in front of his hotel, a dozen men with missing limbs would hang out, begging for money to support their families. “They’re the ones who might have been successfully treated with appropriate cleaning and skeletal stabilization,” he reflects.

While it may be too late to help these particular men, doctors across Africa – and in the rest of the developing world – are rapidly mastering limb-saving techniques, thanks to Coughlin, Morshed, and other UCSF surgeons. “Ultimately, what we want to do is to make ourselves completely obsolete,” says Morshed. “That would be success.”