Published June 14, 2022; updated June 24, 2022

It’s a bad time to need an abortion in the United States. For nearly 50 years, Roe v. Wade, the landmark Supreme Court decision that guaranteed a constitutional right to an abortion, prevented states from banning the practice outright. No more. The court’s June 24 ruling on a Mississippi abortion case is as abortion advocates had feared: Roe has been overturned, and states now have carte blanche to regulate or ban abortion as they please.

The near future of abortion access is certain to be bleak. Anticipating Roe’s demise, Texas, Idaho, and Oklahoma had recently enacted laws prohibiting an abortion as early as six weeks, before many women are able to get one. Now that Roe has fallen, so-called “trigger bans” have outlawed all abortions in those states and 10 others, and more bans will likely follow. Abortion will effectively become illegal in half the country, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which researches and supports abortion rights.

Practically speaking, an abortion was already difficult if not impossible to obtain in wide swaths of the U.S., even with Roe intact. Since 1973, the year Roe was decided, statehouses placed over 1,300 restrictions on the practice, compelling more and more clinics to slash their services or shut down. As of 2021, fewer than 800 abortion clinics remained nationwide – down from 2,700 in the 1980s. Several states had only one left; almost 90% of counties had none.

Without Roe, more than 36 million women in 26 states will lose access to abortion care.

Without Roe, this patchwork will be stretched even thinner. More than a quarter of U.S. abortion clinics will be forced to close, primarily those in the South and Midwest, according to a new study from UC San Francisco. Waves of people seeking abortions will spread across the country, flooding clinics in states that continue to allow the practice, including California. Many more people will resort to illegal abortions or will try to manage them on their own, without medical supervision. Others – primarily poor women of color – will carry to term pregnancies they didn’t want, which will threaten their physical health, financial stability, and personal ambitions and the well-being of their families, as research from UCSF has shown.

Behind the scenes, abortion providers and activists have been gearing up – fundraising, establishing care networks, and passing bills to protect and expand access to abortion in “haven” states. (“We’ll be a sanctuary,” Governor Gavin Newsom declared of California.) Medical academics, too, are rallying – including at UCSF, which has long been a model for abortion provision and training and one of the few institutions to study abortions and their impact on people’s lives.

Abortion experts at UCSF’s Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health are arranging to serve more patients and are pioneering new means of delivering care. They are documenting the impact of the growing number of restrictions and bans, showing who is most endangered and how the damage can be lessened. And they are working to ensure that the next generation of providers – ob-gyns, family doctors, nurses, physician assistants, and emergency room staff – learns the skills necessary to care for pregnant people, whether or not they choose an abortion.

“It’s going to be bad for a while,” says Jody Steinauer, MD ’97, PhD ’19, the Bixby Center’s director and UCSF’s Philip D. Darney Distinguished Professor. “But hopefully, the harm that’s done will make people come to their senses. I have to believe we can turn the tide.”

Jody Steinauer, director of the UCSF Bixby Center, also runs the Ryan Residency Training Program, which has helped more than 100 obstetrics and gynecology departments train over 7,000 residents in abortion care. She estimates that abortion training is now in jeopardy for 44% of U.S. ob-gyn residents.

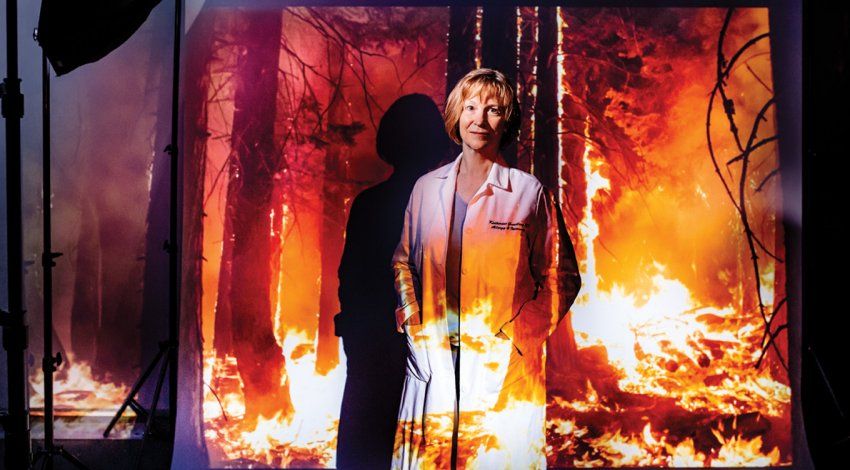

Karen Meckstroth is the director of the UCSF Center for Pregnancy Options, which cares for people having miscarriages and abortions. She is preparing for an influx of patients from states that ban abortion

Bracing for a Tsunami

The most urgent problem is logistical. Across the country, clinics in states where abortion will stay legal are scrambling to figure out how to accommodate the influx of patients that could start as early as July. “The word we keep hearing again and again is ‘tsunami,’” says Carole Joffe, PhD, a UCSF sociologist who has been collaborating with Drexel University law professor David Cohen, JD, to interview abortion providers. Many foresee the surge sweeping up even women who live in haven states, as streams of abortion seekers from the South already are. “Before Oklahoma banned almost all abortions, so many Texas women had gone into the state that Oklahoma women couldn’t get an appointment for three or four weeks out,” Joffe explains. So they tried Colorado or New Mexico instead, displacing women there. “There’s a domino effect.”

California could see especially large abortion-related migration. “We’re already getting calls from Texas and other states,” says Karen Meckstroth, MD, MPH, who runs the UCSF Center for Pregnancy Options, which cares for people having miscarriages and abortions. She has started to extend the clinic’s operating hours and to recruit providers who work in labor and delivery and high-risk pregnancy care to perform abortions. She is also partnering with other abortion clinics and non-profits – including Access Reproductive Justice, a hotline in Oakland – to help callers who can’t come to UCSF find care closer to home. “Even with financial support, there are people who can’t travel,” Meckstroth says. “They might have childcare issues, or they can’t take time off work.”

Those forced to travel may find it takes them longer to come up with funds or to make arrangements. That means providers will see more patients later in their pregnancy, raising a risk (albeit small) of complications, says UCSF’s Eleanor Drey, MD, EdM, who directs the Women’s Options Center, the abortion clinic at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. (Major complications of legal abortion occur in barely one-quarter of 1% of cases, making the procedure safer than having a wisdom tooth removed.) Although most abortions (over 90%) take place in the first trimester, Drey’s clinic regularly serves patients past that mark, including some from out of state, because they have few other places to go. “People often are quite judgmental about anyone needing a later abortion,” she says. “Even if they support abortion overall, they’re like, ‘But why did she wait so long?’”

Drey’s research shows that usually a woman seeking a later abortion doesn’t know she’s pregnant for weeks or even months; she may mistake bleeding for menstruation, for example, or think a missed period is normal. “Once she realizes she needs an abortion beyond the first trimester, suddenly everything snowballs,” Drey says. The procedure gets more medically complex, the cost goes up, and finding a provider willing or able to do it gets much, much harder. Many people who seek abortion care don’t make it to a clinic in time. And with clinics becoming fewer and farther between, abortion experts are having to think creatively about how to increase access in other ways.

One approach gaining ground is telemedicine. Early in pregnancy, an abortion can be done with a simple procedure to evacuate the uterus (what’s known as manual uterine aspiration) or with medication (typically, a two-drug combination of mifepristone and misoprostol). Until recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required patients to pick up mifepristone in person at a medical facility, purportedly as a safety precaution. “It was very paternalistic,” says Ushma Upadhyay, PhD, MPH, a reproductive health scientist at UCSF. She points out that mifepristone, which blocks a hormone that maintains a pregnancy, is safer than many drugs available in pharmacies, like Viagra. But when the COVID-19 pandemic curtailed in-person visits, the FDA lifted that requirement, paving the way for many people to get abortion care entirely online.

Since then, Upadhyay’s research team has followed more than 3,000 patients across the U.S. who used a telehealth service for a medication abortion. These virtual clinics, which proliferated during the pandemic, allow patients to consult with providers through an app or video call and then receive their abortion pills by mail. The researchers are still processing the study data, but an early analysis of 141 California participants found that medication abortion through telehealth is safe and effective; many patients, several of whom were already parents, said they appreciated being able to fit the care into their busy lives. “One woman who is a driver for Amazon just pulled over and had her video visit from her truck,” Upadhyay says. The FDA considered that study’s findings in a recent decision, announced in December 2021, to permanently allow pharmacies to dispense mifepristone by mail after the pandemic ends.

But even with the FDA’s blessing, telehealth for medication abortions won’t be allowed everywhere, as 19 states already forbid or restrict its use. Still, there may be legal strategies for navigating this new landscape. California, for instance, is considering bills that would protect its abortion providers from being held liable in civil court or from losing their medical licenses if they care for patients living in states where abortion is illegal. “There may be an opportunity for providers in California to step up and serve patients across state borders,” says Daniel Grossman, MD, who leads UCSF’s Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH, pronounced “answer”), a research group that includes Joffe and Upadhyay. He and other ANSIRH researchers are also exploring the feasibility of making abortion pills available over the counter or of prescribing them to people who aren’t pregnant but are worried about that possibility – a strategy called advance provision. “I see this as a wraparound service,” Grossman says, “where patients might be given abortion medication ahead of time and told they can always call the clinic or have a telehealth visit if they’re considering using it.”

Meanwhile, if you Google “what to do if my period is late,” you may come across an ad for a newly launched study led by Upadhyay of what she calls the late-period pill. It’s an option for people who think they might be pregnant and don’t want to be. The regimen is three doses of misoprostol alone, which is commonly used to prevent stomach ulcers and to treat miscarriages, taken up to 14 days after a missed period. “It causes the uterus to contract and empty,” Upadhyay says, and won’t harm someone who isn’t pregnant. She is recruiting early adopters in hopes that their experiences will prove the late-period pill to be one more accessible, dignified choice at a time when many people will have so few options open to them.

Daniel Grossman, the director of UCSF’s Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health research group, is exploring the feasibility of making abortion pills available over the counter or via advance provision – the strategy of prescribing the pills to people who aren’t pregnant but are worried about the possibility.

Ushma Upadhyay’s research shows that providing abortions remotely, with video or chat visits and provision of pills by mail, is safe and effective. Her findings informed the FDA’s recent decision to allow telehealth abortion care. “Health care policy should be based on evidence,” she says.

Bearing Witness

Whatever you believe about when life begins and what it means to end a pregnancy, the reality is that making abortions hard to get hurts women. Between a quarter and a third of women in the U.S. have an abortion during their lifetimes. Yet every year, thousands of women carry undesired pregnancies to term because they can’t afford an abortion or – for more than 4,000 women a year, according to a UCSF analysis – because they can’t get to a clinic that performs abortions at their gestational point. Diana Greene Foster, PhD, a UCSF demographer and member of ANSIRH, estimates that with Roe now vacated, the number of people who want an abortion but can’t obtain one could be as high as 100,000 a year.

Foster understands better than most the impact this scenario will have on women’s lives – and the lives of their children. In 2007, she embarked on a decade-long study involving more than 40 researchers and about 1,000 women – some who’d received abortions, often after barely making it to a clinic, and others who’d arrived too late. She called it the Turnaway Study “because ‘turnaways’ is what [my UCSF colleague] Dr. Drey calls women who are too far along in their pregnancies to receive an abortion at her hospital,” Foster writes in her book The Turnaway Study. It was the first study of its kind and, by scientific standards, exceptionally robust. And the results were a bombshell.

Compared with women who got an abortion, Foster’s team found, women denied one were worse off on just about every measure. Their physical health was worse. Their mental health was worse for a time. They had fewer life aspirations. They had contact with abusive partners or ex-partners for longer. They were more likely to be single parents with no family support. They were less likely to have full-time employment and be able to make ends meet. And those who were already mothers – more than half the sample pool – had a harder time providing for their other children. “It’s not pro-child to prevent people from getting abortions when they feel they need them,” Foster says. “It’s making people have kids under worse circumstances than they’d want.”

“It’s not pro-child to prevent people from getting abortions when they feel they need them. It’s making people have kids under worse circumstances than they’d want.”

Diana Greene Foster, PhD

Foster led the Turnaway Study, a groundbreaking investigation into the effects of unwanted pregnancy on women’s lives.

Of course, losing access to legal abortion care won’t stop everyone who wants an abortion from having one, and Foster is planning and fundraising for a study that will document what happens to people trying to get abortions in states that will ban them now that Roe has been toppled. “I would like to know who is affected by these laws,” she says. “Who is able to get an abortion by traveling? How much does it delay them, and at what cost, physically and financially? Who tries to have an abortion by themselves? Who is at risk of doing self-harm? If we can identify those people, we can tailor outreach to them.”

The vast majority of people who manage their own abortions will probably use medication, which is “extremely safe,” Drey says. Those who can afford it can buy pills from websites that offer them without a prescription or can go to Mexico, where misoprostol is sold over the counter. (Researchers who analyzed pills sold illegally online found that their contents were as advertised, though sometimes in weaker doses.) “It’s not going to be like before Roe,” Drey says, when medication abortion didn’t exist and at least 1,000 women a year died from botched, back-alley surgical abortions. That’s not to say there won’t be tragedies. “We know people do things that are desperate,” she says, although very rarely. “Even in California, we see patients who ask their boyfriends to hit them in the stomach,” she notes, and others who ingest toxic substances or stick instruments into their uteruses.

But the symbol of post-Roe America won’t be the coat hanger – it will be the jail cell. Even with Roe in place, feticide laws and other punitive provisions were used against women thought to have self-induced an abortion. “There already have been arrests,” Joffe says. “I foresee a lot more.” People will be investigated not only for having an abortion themselves or helping someone else have one but even for spontaneously miscarrying or suffering a stillbirth, as is sometimes the case even today. “There are people who have the tragedy of losing a pregnancy and then are accused of having caused the loss,” Joffe says.

In general, the consequences of abortion bans will fall most heavily on people who are the least advantaged. Minors and people who are poor or undocumented often won’t be able to travel, to pay for a procedure or pills (by law, federal Medicaid cannot cover abortion), or to reach providers online. Women of color will be more likely than white women to continue an unwanted pregnancy, because they are more likely to live in states where abortion rights are threatened or where access is scarce. And they will be more likely to die in childbirth. On average in the U.S., 24 women die for every 100,000 live births, far more than from legal abortions. In many states where abortion is now or will soon be banned, rates of maternal mortality are even higher, especially among Black and Indigenous women.

“It’s going to be marginalized communities that suffer the most,” says UCSF ob-gyn Biftu Mengesha, MD, MAS ’17. “For me, as a Black woman who came to this work to help elevate the quality of care for people who share my identities, … honestly, it’s terrifying.”

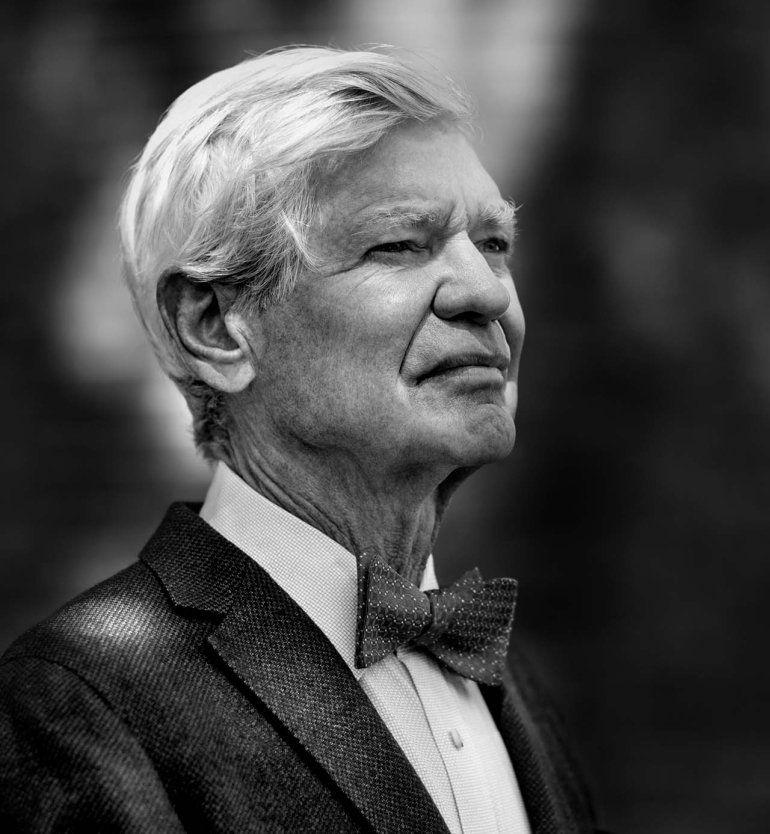

Philip Darney, a founder of the UCSF Bixby Center, also founded the UCSF Fellowship in Complex Family Planning, which trains ob-gyns to become leaders in abortion care and research and serves as a model nationwide.

Uta Landy, a senior advisor at the Bixby Center (and Darney’s wife), founded the Ryan Residency Training Program, which has helped integrate abortion training into ob-gyn residencies across the U.S., Canada, and Puerto Rico. Thanks to her and Darney’s pioneering work, support for equitable access to abortion within the medical community is stronger than ever.

Confronting the Training Crunch

The reversal of Roe won’t just upend abortion provision. It will also mean there will be fewer doctors well-trained to care for patients who are or might get pregnant. (In some states, including California, nurses and physician assistants can also provide early abortions.) Studies show that medical residents who train in abortion as part of their regular rotations are better able to counsel patients about birth control and pregnancy options and to handle complications of pregnancy loss. “The skills that we use for early abortion care are the same skills used for contraceptive services and miscarriage management,” says Lealah Pollock, MD ’11, MS ’08, who oversees abortion training in the family medicine residency at UCSF and holds the Vitamin Settlement Professorship of Community Medicine.

Today, more than 90% of ob-gyn residents in the U.S. have access to some level of abortion training. That was not always the case. In the decades after the Roe decision was issued, stigma and anti-abortion violence helped drive the practice out of many hospitals, including at teaching hospitals affiliated with medical schools; abortions increasingly became the purview of freestanding clinics, such as those run by Planned Parenthood. By the mid-1990s, few teaching hospitals performed abortions, and as a result, few medical residents pursued abortion training.

The Bixby Center’s Jody Steinauer and others at UCSF have led the charge in reversing that trend. In 1993, Steinauer took a year off from medical school to start Medical Students for Choice, a group that has advocated for the inclusion of lectures about abortion in medical school curricula and that now has over 220 chapters worldwide. Around the same time, Bixby co-founder Philip Darney, MD ’68, together with Uta Landy, PhD, a senior adviser to the Bixby Center (and Darney’s wife), launched programs that help medical schools integrate abortion training into ob-gyn residencies and establish fellowships in complex family planning – an ob-gyn subspecialty that focuses on abortion and contraception. Through these programs, one of which Steinauer now runs, more than 100 campuses in the U.S., Canada, and Puerto Rico have trained over 7,000 residents and 600 fellows. Many of them have gone on to lead abortion training and research at universities and to provide abortions across the continent, including in conservative states.

Biftu Mengesha chose to become an ob-gyn to “help elevate the quality of care for people who share my identities.” Without the protection of Roe, she fears, “it’s going to be marginalized communities that suffer the most.”

Jennifer Kerns directs a UCSF fellowship in family planning for ob-gyns. If many medical schools are forced to stop teaching abortion, she worries, “what’s going to happen to abortion training?”

“We’re everywhere,” says Sanithia Williams, MD, a former UCSF fellow who is one of only a handful of abortion providers in Alabama. She worries about what she will do if her clinic has to close. “It’s fundamental to my philosophy as a provider to be able to give people the options to make the decision that’s best for them,” she says. “If my hands are tied by the state, I don’t know how I’m going to process that.” She might fly in to help in clinics where abortion is still legal, she thinks, or look into telehealth opportunities. “I don’t think I would leave,” she adds.

But other providers are already moving out of anti-abortion states, including two former UCSF trainees who recently relocated from Texas to Montana and Colorado. “Talented, excellent doctors are going to be leaving states that need them,” says Mengesha, who directs UCSF’s complex family planning fellowship with Jennifer Kerns, MD ’04, MPH. Many states trying to ban abortion already have a shortage of physicians, she notes. With even fewer providers available, access to high-quality health care will only get worse, particularly in poor and rural areas.

Talented, excellent doctors are going to be leaving states that need them.”

Compounding the problem, states that outlaw abortion will also be less capable of training new doctors to replace the ones that flee. If medical schools in anti-abortion states are forced to stop teaching the practice, 44% of ob-gyn residents (more than 2,600 of them) won’t have access to abortion training, according to an analysis by Steinauer and others. Many trainees and future applicants will thus look for education elsewhere. UCSF has begun welcoming visiting residents from Texas, but capacity is limited. “Training someone is a big task,” Mengesha says. “There’s going to be a huge pool of people who want to get trained in abortion and not enough bandwidth to support them.”

The exodus of abortion providers from restrictive states will leave abortion there largely in the hands of primary care and emergency physicians. “It’s going to be critically important for family doctors to connect people with services,” says Christine Dehlendorf, MD, MAS ’08, the director of a UCSF fellowship for family physicians who want to specialize in abortion and contraception care. “Even if we can’t provide abortions ourselves, then we should be able to facilitate people getting the care that they need.” ER doctors will also see more abortion-related visits, either because of complications or because some people who self-manage an abortion might worry about how much bleeding is normal or whether their method has worked. “Are our emergency medicine colleagues ready to deal with this?” Steinauer asks.

But if there is a silver lining in the dark morrow of abortion care in America, it is that the systems put in place to support access to it are here to stay. “We’ve integrated abortion into mainstream medicine in a way that you can’t take away anymore,” Landy says. She and Darney, who began their careers before Roe, are optimistic that the pendulum swing of abortion rights will again be reversed. Because however contentious the political battle becomes, they point out, the medical community at large remains committed to the belief that abortion is an essential part of reproductive health.

There’s no denying that the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe endangers women’s health and livelihoods, Darney says. “But our capacity to do something about it is a lot better.”