On the morning of November 8, 2018 – as the skies above Paradise, Calif., sickened from a faint blue to ashy brown to blood red; as flames thundered and cracked through forest and town, incinerating homes and melting cars; and as thousands of terrified residents packed onto narrow, gridlocked roads – Amber Denna dashed into Paradise Drug, where she was a longtime employee. She snatched the pharmacy’s computer server and threw it, along with a few personal possessions, into the back seat of her car.

On the phone with a colleague in nearby Chico, Calif., Denna had realized that the thousands of records stored on that server would be a lifeline for any nursing home patients, retirees, and families who’d manage to escape the devastation of the Camp Fire. Within just a few hours, most of the town’s 26,000 inhabitants would lose everything. But those who survived would still need their medicine.

Owned and operated by Janet Balbutin, PharmD ’68, Paradise Drug had been a hub of sorts for the community, as well as the first point of contact that many of its residents had with the medical system. With the data rescued from the fire, Balbutin ended up dispensing hundreds of free or deferred-payment medicines to those dispossessed residents. “Even now, we just stand back and say, ‘What happened?’” says Balbutin. “To wipe out a town in three hours at the most.... We lost a lot of patients in the fire.”

The Camp Fire was hardly the first, or even the worst, climate crisis-related disaster to upend human lives. The European heat wave of 2003, the first weather disaster to be widely linked to climate change, killed between 35,000 and 70,000 people, overwhelming hospitals and morgues. In 2012, unusually warm waters off the coast of Florida caused an algal bloom that resulted in $540 million in hospital admissions and emergency department visits. And when Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in 2017, it killed 3,000 people and wiped out countless Puerto Ricans’ access to food, social services, and health care; in addition, it destroyed the supply chain for 44% of U.S. IV bags, creating months-long shortages at hospitals across the country and beyond.

There are only four scenarios that could actually kill hundreds of millions of people. Nuclear war, meteorites, and pandemics are all merely feasible. But climate change is already underway.”

Sir Richard Feachem

“The climate crisis creates so many more human health impacts than we typically think of,” says Wendy Max, PhD, a health economist in the UC San Francisco School of Nursing. In a recent study, Max and her co-authors looked at 10 climate change-fueled disasters in 2012 in regions across the U.S., including hurricanes, fires, disease and allergen outbreaks, heat waves, and spikes in ozone pollution. Far from a comprehensive list, these 10 events alone led to 917 deaths, 20,568 hospitalizations, 17,857 emergency department visits, and $10 billion in health-related costs. Such events kill, they pack ERs, and they leave lingering legacies of toxic pollution, pulmonary complications, and post-traumatic stress – but they are just a glimpse of what’s to come unless the world makes an extraordinary course correction. “There’s a profound human cost here and now,” Max says. “Hopefully, seeing that helps elevate our understanding of the urgency.”

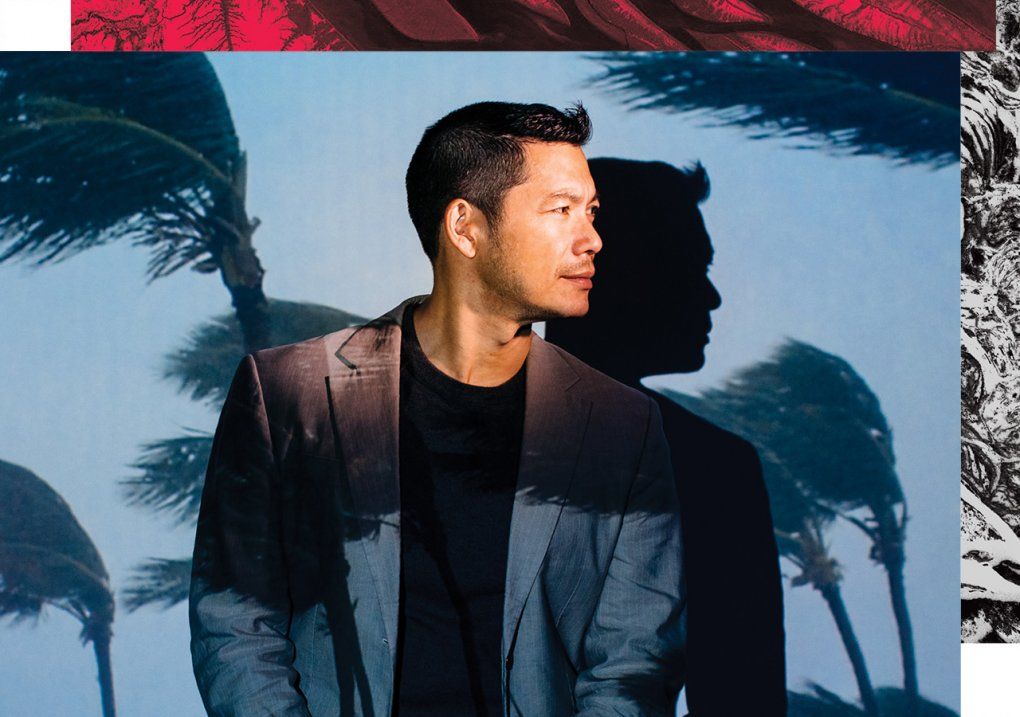

If anyone feels that urgency, it’s Katherine Gundling, MD. A year ago, Gundling sat in her allergy-immunology clinic at UCSF’s Parnassus campus, a stethoscope cupped to the ribs of a patient. The young woman’s severe asthma had long been well controlled, but now her breathing was labored, with coarse wheezing audible all around her chest. Outside, smoke from the 2018 Camp Fire was choking San Francisco, and it had affected this woman so profoundly that Gundling’s only recourse was to prescribe a powerful new medication. After years of seeing her patients suffer from ever-longer allergy seasons and “the increased nastiness of the pollens,” this was the last straw. She was ready to get to the root of the problems she was seeing, and within a few months, Gundling had retired from her practice in order to focus on the relationship between climate change and human health. “I realized that I could not leave this planet without doing everything I could to affect what’s happening,” she says.

Trying to help a patient severely affected by smoke-filled air drove physician Katherine Gundling (left) to pursue a new career in climate medicine. “There’s a profound human cost here and now,” says health economist Wendy Max (right), who studies the impact of climate-change-fueled disasters.

She dove in headfirst, learning about advocacy and joining the board of an international environmental group. She began reaching out to colleagues at UCSF and elsewhere – building a list of clinicians, health scientists, and corporate and nonprofit allies who shared her sense of urgency. Most notably, she connected with a group of UCSF students passionate about medicine and climate. “Students from all four schools were saying, ‘Hey, why isn’t everybody up in arms about this?’” Gundling says. Soon, she found herself mentoring them on career paths that could combine the health sciences with climate action, even accompanying several of them to Washington, DC, to educate legislators on the climate-health connection.

Inspired by these students, Gundling envisions a new medical career path, including a dedicated climate-medicine fellowship designed to equip health professionals with the expertise to prepare for and address climate-related medical disorders. “In 2050, the public health challenges will be much greater than today,” she says. “Our current medical training is not set up for this at all. We will require many more and larger facilities to treat acute and chronic climate-related illnesses. Students in the health professions will need to go out to these facilities, where senior physicians must provide proper training. Who will do this?” she says. “To complicate matters,” Gundling continues, “severe weather events will vary widely by location. For example, doctors in flood-prone Houston will need training related to mold, infectious diseases, and water contamination, while those in Northern California must respond to wildfire-related illnesses. Our need for public health specialists will also be much greater. And along with this is coordination with governmental services such as 911 during acute events. Could specially trained nurses or doctors handle these calls instead of police, who have minimal training?”

Infectious disease specialist Peter Chin-Hong says that his students will encounter diseases never before seen in California.

While these are daunting questions, the idea of incorporating climate change into medical education is already gaining momentum at UCSF and beyond. The changing climate will have profound implications for how tomorrow’s physicians must think about certain diagnoses. Infectious disease specialist Peter Chin-Hong, MD, notes that the students he is teaching today will surely encounter diseases that have never before been seen in California. “They need to know that with changes in climate, diseases have no borders anymore,” he says. “When somebody presents with something that looks like dengue, for example, the physician will need to be suspicious of that and be able to send the right tests, even though it’s not in the textbooks.”

“Things are changing so fast,” he continues. “We’re not trying to teach the whole encyclopedia like we used to, but a way of thinking and a habit of mind. We need to give students the tools they need to solve the future problems we don’t even know about yet.”

UCSF’s Sheri Weiser, MD, MPH, and Arianne Teherani, PhD, have shown how. Together, Weiser, an epidemiologist and practicing internist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, and Teherani, a professor of medicine and education, developed a climate-health curriculum for learners across all of the health sciences. In addition, they’ve trained faculty members at all six University of California health campuses. Aside from an elective on climate change and health that’s available to first-year medical students, their approach does not add stand-alone climate-science lessons. Instead, they train professors to integrate relevant knowledge and case studies into existing material. Professors of anesthesia, radiology, and pharmacy, for example, are encouraged to note that anesthetic gases, imaging technologies, and pharmaceuticals all have a significant carbon footprint. In psychiatry, students learn how most psychiatric drugs interfere with the body’s ability to regulate temperature, creating life-or-death stakes for depressed or mentally ill patients during heat waves. Training in infectious diseases already covers the pathogens found in contaminated water and transmitted by insects; highlighting the health implications of increased flooding and expanded mosquito habitats is a simple, and essential, connection.

Epidemiologist Sheri Weiser is training professors across the University of California health campuses to integrate climate health into existing coursework.

The approach is effective, and it has put UCSF’s climate change education efforts ahead of those of most other medical and health professions schools, but Weiser and Teherani are eager to expand the program, both within and outside of UCSF. “Literally the biggest threat to human health ever seen is in front of us right now,” says Weiser. “So why is this not front and center of everything? Why is it not being talked about all the time?”

Colin Baylen, a second-year medical student who co-founded the UCSF student group Human Health + Climate Change, puts it this way: “When I think about what my career might look like in 2050, I see climate change impacting any specialty I consider.”

Even the best-case climate scenarios for the decades ahead look pretty bleak. “There are only four scenarios that could actually kill hundreds of millions of people,” says Sir Richard Feachem, DSc(Med), PhD, director of UCSF’s Global Health Group. “Nuclear war, meteorites, and pandemics are all merely feasible. But climate change is already underway.”

Between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year worldwide from malnutrition, vector-borne diseases, diarrhea, and heat stress. By 2050 in the U.S., annual cases of West Nile virus – just one of the many infectious diseases that are projected to explode – will more than double. At least one projection estimates that by 2050, more than 3,400 additional Americans may die each year from heat stress. And the most vulnerable among us will suffer the most: poor people, the young, the old, pregnant women, and people with depression or mental illness.

Perhaps even more consequentially, climate change will displace hundreds of millions of people by 2100 – particularly near the equator, along coastlines, and in regions struck by drought. Extreme heat, food and water insecurity, rising sea levels, and natural disasters will uproot millions, isolating entire communities from the health systems they depend on and placing new burdens on health resources wherever those climate refugees end up. And this will happen not just in far-off places like India, Africa, and the Middle East; climate pressure in Central America is already adding fuel to the U.S. border crisis, and the World Bank projects that climate change will turn 1.7 million residents of Mexico and Central America into climate migrants by 2050.

On top of all this, the impacts of climate change on mental health are incalculable. Every hurricane, firestorm, flood, and deadly heat wave triggers waves of trauma and PTSD. Lost ways of life – whether in eroding seaside communities, on slowly dying farms, or in scorched mountain towns – exact an existential grief known as solastalgia. And acute and long-term changes connected to climate have been shown to elevate both interpersonal and intergroup violence, while undermining social identity and cohesion.

Ironically, the vastness of the problem is also connected to society’s failure to adequately respond to it. “Climate distress often immobilizes us,” says Elissa Epel, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and an expert on chronic stress and stress resilience. “We look like we don’t care, but it’s because we can’t cope. The scope of our world’s endangerment is so enormous that it makes us feel helpless. We become passive and collusive with what’s happening.”

The solution, Epel says, is to build personal and group resilience as a bulwark against the psychological toll of the climate crisis: “Part of dealing with climate distress is really letting ourselves have some space, support, and guidance” for processing our emotional reactions. “We’ve been looking at climate science to deal with climate change, but now, it’s not about science. It’s about human behavior and getting over our barriers.”

Listen : A conversation with psychiatry professors Elissa Epel and Dan Siegel on climate stress, “from delusion to resilience”

Epel says that in the past, the way she has dealt with her own climate distress was “cheerleading others and saying, ‘Let’s see what’s happening with the environmental activists, the climate scientists. What are they going to do?’” But now, she says, “I feel desperation about doing all I can in my own personal ecosystem.” With that in mind, she recently agreed to co-lead, with Andreea Seritan, MD, a new UCSF task force on climate change and mental health, a group that’s focused on research, training, and partnering on broader climate efforts at UCSF. Getting personally engaged in solutions is helping her live with her own climate anxiety. She hopes the task force will become a model for the world because “we have so much power as a university and as a health system.”

Graduate student Naomi Beyeler authored a “call to action” for climate-change engagement that more than 100 of the world’s most respected health organizations endorsed.

One important player flexing that power at UCSF has been Naomi Beyeler, MPH, who is both the staff lead for the Global Health Group’s climate change and health initiative and a PhD student focused on researching the impacts of climate change on health care delivery in low-resource settings. In 2018, Beyeler organized a global forum that drew nearly 300 government and global health leaders to UCSF. The event culminated with a “call to action” endorsed by more than 100 of world’s most respected health organizations. Beyeler was the key author of that rallying cry, which frames two ways that the health sector must engage with the issue:

She calls one approach “health action for climate,” noting that the health sector – which accounts for a stunning 10% of the U.S. carbon footprint and 5% globally – can play a significant role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions by greening its own practices (see sidebar). On the flip side, Beyeler says, there is “climate action for health.” Essentially, this means that health scientists and caregivers should embrace the role of climate messengers because “every policy in the climate space is going to affect health.” She notes that “some of those pathways are going to benefit health more than other alternatives, so the health sector has a real stake in being engaged in climate policy.”

For example, shutting down dirty power plants, investing in local food systems, and creating green urban spaces all cut carbon emissions while also making communities – particularly underserved ones – healthier. “When we as a society finally choose to intervene, we can not only prevent many of the worst scenarios from happening,” says Katherine Gundling, “but we can also address health disparities in the process.”

“I’m an optimist because there are so many things we can do,” she says. “The question is, are we going to define the future, or are we going to react to it?”

Health professionals could play an outsized role in defining that future because, according to Gallup, people trust them more than those in any other professions. “When physicians and nurses get out there and talk about something, people sit up and say, ‘Let me pay attention. These are people I respect and believe,’” says Wendy Max, the health economist. Leveraging that trust to illuminate the health impacts of climate change elevates science above politics. And, of course, it shifts the stakes from abstract, seemingly distant ideas like sea level rise to deeply personal, universal concerns for our own well-being and that of our kids.

In September, Karly Hampshire, Nuzhat Islam, and Sarah Schear made exactly that argument to some of the most powerful people in Congress. On the same day that 7 million people across the globe were striking for climate action, these three UCSF medical students joined more than a dozen physicians to lobby California Senators Kamala Harris and Dianne Feinstein; Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, from California’s 12th district; and Representative Barbara Lee, from California’s 13th district, on climate issues. “We encouraged them to link climate change to human health whenever possible, allowing people to internalize climate change and make them realize that it is not about someone else, somewhere else,” says Hampshire. “It’s their kid’s asthma, their best friend’s fire-related PTSD, their dad’s heat stroke.”

UCSF medical students are confronting the climate crisis.

Like most of the people in this story, Hampshire has vivid recollections of the day in 2018 when Paradise burned and of the weeks that followed. Soupy, noxious air choked the city. Everywhere, faces were hidden behind N95 masks or tightly wrapped scarves. “It was such an eerie time, as if out of a sci-fi movie,” she says. “I remember thinking: Is this what the world is going to look like all the time? Is this the type of place I’m going to raise my children?”

For many in the Bay Area and beyond, the hazy, toxic glow of the Camp Fire-polluted skies seemed to illuminate the truth most of us have known but, as Epel puts it, are too “frozen” to grapple with: The climate is changing, here and now, and San Francisco is no less vulnerable than Miami, Damascus, or Manila.

That knowledge can feel bleak, but it comes with one tremendous upside: It can catalyze action. “We know what’s ahead of us,” says Gundling. “But we also know we can bend the curve. Some people may see addressing climate change as a moral imperative. But as health care professionals, it’s much more tangible than that. The moral imperative to engage with the climate crisis grows out of the consequences we see for our patients.”

UCSF Magazine

Dive into the future of health in this special issue of UCSF Magazine.