This is a story of another time, of a plausible future 30 years from now, give or take, in which the human experience of life and health (and perhaps even of who we are) will unfold unlike anything known before. The citizens of this future will learn early in life – through some combination of next-next-next-generation genetic testing and intelligence gleaned from their smart accessories – whether they are heading toward disease: depression, dementia, diabetes, what have you. More importantly, they will be offered an exit strategy.

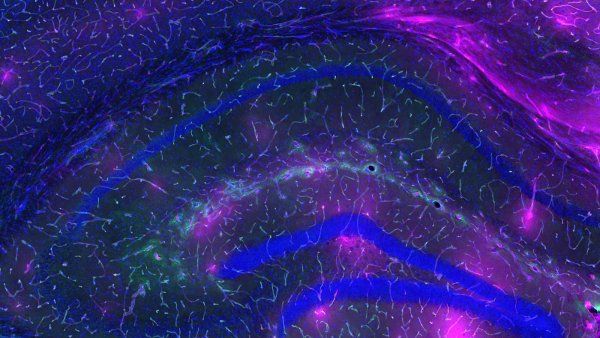

Some future citizens will take a familiar route: medications, behavioral therapies, or lifestyle modifications. But for others, the path to well-being will require novel interventions. For example, those genetically predisposed to certain disorders might opt to get any risky DNA snipped out of their genes or rewritten. Those with neurological diagnoses, meanwhile, might be prescribed a brain implant – a clingwrap-like electrical film laid on the brain’s surface, perhaps, or a network of thinner-than-hair wires snaked within its anatomy, to keep its neural circuits firing properly.

One might think, assuming these procedures have been shown to work safely and well, that future societies will have everything to gain and little to lose. Who wouldn’t divert the course of their own health, or their children’s, to avoid suffering down the road? And yet our neurons and our DNA are more than the origins of illness. They are also the substrates of our being: our identity, our humanity, arguably consciousness itself. Once we begin to manipulate these elements for medical purposes, do we not risk altering who we are?

If a gene therapy or brain implant erased, say, a person’s propensity for depression, would it also erase possibly related facets of their personality, such as introversion, pensiveness, or melancholia? Would they recognize strange thoughts or behaviors as side effects or mistake these changes for a “new normal”? And if they chose not to have these treatments, or couldn’t afford them, would they be passed over for jobs, for health insurance, for social acceptance? Who would they be? Would they still be themself?

The Bionic Human

Since before the first Homo sapiens walked the Earth 200,000 years ago, we humans have been shaped by our own inventions. Fire control, stone tools, eyeglasses, the cotton gin, electricity, antibiotics, the atom bomb, the heart transplant, in vitro fertilization, the internet – for better or for worse, technology has long fashioned us as individuals, as societies, and as a species. Still, there is something exceptional about the prospect of gaining mastery over our brains and genes.

These devices are part of an evolution of thinking about the bionic human.”

First, consider brain implants. In the past couple of decades, surgeons have installed them in hundreds of thousands of patients with epilepsy, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and movement disorders, including Parkinson’s. The implants relieve symptoms like seizures or tremors by sending electrical pulses to culpable brain areas – a technique known as deep brain stimulation. Many experts believe its use will only expand as implants get smaller and more sophisticated and as implantation surgeries become less invasive. “I wouldn’t be surprised if, in 20 or 30 years, such devices will be as ubiquitous as cardiac pacemakers,” says Edward Chang, MD ’04, a professor of neurological surgery and the William K. Bowes Jr. Bio-medical Investigator at UC San Francisco. He and some of his colleagues have even begun to refer to implants in the brain as “brain pacemakers.”

Unlike heart pacemakers and other synthetic body parts, however, brain implants could challenge the typical ways we think about human augmentation. “There’s no question these devices are part of an evolution of thinking about the bionic human – how we can modulate and tinker with ourselves to replace or restore functions,” says Chang, who, together with UCSF colleagues, is now testing several applications for the technology, including whether it can help treat mental-health problems and restore movement and speech to patients with paralysis. “But now we’re talking about directly interfacing with the brain, which is much more salient than something like a hip replacement or an artificial kidney, because it has to do with the mind.”

Edward Chang

professor of neurological surgery and member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences

Gene therapies, too, carry a special philosophical weight, bearing upon not the human mind but our genome – the complete set of DNA whose molecular code, and how it’s expressed, give rise to a singular life. These therapies insert or modify DNA in human cells to overcome genetic disease or turn cells into living drugs. Since 2003, regulatory agencies in China, Europe, and the U.S. have approved fewer than a dozen gene-therapy products, including those for certain cancers and disorders of the blood, eye, and neuromuscular system. But the technology holds promise for countless cures.

“Within 30 years, it will probably be possible to make essentially any kind of change to any kind of genome,” says Jennifer Doudna, PhD, a professor of chemistry and of biochemistry and molecular biology at UC Berkeley. She became world renowned in 2012 for her work on a genome-editing tool called CRISPR-Cas9 and now co-directs the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI), a partnership between UCSF and UC Berkeley that explores potential uses of genome-editing and its societal implications. “You could imagine that, in the future, we’re not subject to the DNA we inherit from our parents,”she says, “but we can actually change our genes in a targeted way.”

Such on-demand editing could be done, as it is today, in diseased tissues like retinas, nerves, or, one day, even brains. But it could also apply, controversially, to reproductive cells and embryos. This latter approach, called germline engineering, would enable genetic changes, therapeutic or otherwise, to be passed on to future generations. “Does that mean directing our own genetic destiny?” Doudna asks. “I say it does.”

Does that mean directing our own genetic destiny? I say it does.”

Given the enormity of this power, many experts, including Doudna in 2015, have called for a moratorium on germline engineering in humans. The latest outcry came this past fall, after a scientist in China claimed to have created twin girls from embryos edited to prevent HIV infection. Although the IGI takes an official stance against the current use of the practice, Doudna thinks it can’t – and perhaps shouldn’t – be stopped indefinitely. Families of children with heritable diseases awaiting cures have changed her mind, she says. “So many parents have emailed me saying, ‘Please help.’ I feel a responsibility to at least explore what it would it take for the science and ethics to be at a place where this kind of editing is safe and responsible.”

The further we explore gene therapies and brain implants, however, the more we will confront the question of what it means, as Doudna puts it, “to control the very essence of who we are.”

Beyond Therapy

Ethicists ask whether these technologies could turn someone into a different person. The concern is not unfounded. Scores of studies show it’s possible to genetically engineer mice to dial up or down just about any behavioral or cognitive trait: aggression, compulsion, sociability, learning, memory, etcetera. Likewise, certain changes to the human brain – traumatic injury or neurodegeneration, for instance – can induce dramatic changes in character, such as emergent criminality or creativity. Even antidepressants go “beyond treating illness to changing personality,” making the shy bold or the solemn cheerful, as psychiatrist Peter Kramer observed in his 1993 bestseller Listening to Prozac.

Jennifer Doudna

professor of chemistry and of biochemistry and molecular biology at UC Berkeley

It’s unlikely that today’s gene therapies would have serious psychological or metaphysical side effects. They typically act on only one gene out of a possible 20,000 in a fraction of a patient’s cells, such as retinal cells or immune cells. But genome editing might one day treat or prevent disorders that involve up to hundreds of genes, including obesity, heart disease, and psychiatric illness.

If and when we use this technology to control such complex health conditions, Doudna speculates, we may inadvertently influence complex personal traits. Genes, after all, don’t work alone but in networks; they often serve multiple functions, which scientists are still uncovering. “In the future, if people are able to edit their children’s genomes,” she asks “to what extent does that alter the nature of the child?”

As for brain implants, ethicists debate the extent of their psychic risks. A minority of patients who have received such implants have said they identify with their device (“It became me”) or feel controlled by it (“You just wonder how much is you anymore”). Do these impressions reflect a distorted sense of self? The answer is murky, says neuroethicist Winston Chiong, MD ’06, PhD, an associate professor of neurology who studies the ethical and policy implications of brain diseases and therapies. “Sometimes these quotes are questionably interpreted,” he explains. In a recent paper, for example, Australian ethicist Frederic Gilbert, PhD, points to a case in which a patient receiving deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease reportedly told her interviewers, “I feel like an electric doll”; some ethicists misquoted the comment as “I am an electric doll.” “While the latter quote may involve a psychotic (delusional) episode,” Gilbert writes, “the former could simply represent a playful and moody remark.”

In other rare instances, patients with implants have become hypersexual, impulsive, or depressed. However, the cause may not necessarily be their device, says Simon Outram, PhD, a research specialist in UCSF’s Program in Bioethics. As part of a two-year study being run in partnership with Baylor College of Medicine and the University of Florida, Outram is helping conduct patient interviews and surveys to examine how brain implants impact autonomy, personal identity, and risk-taking. “It’s very difficult to separate the progress of the illness from the effects of the treatment itself,” he says.

The fear that a brain implant may threaten one’s personhood “maybe isn’t bearing out as we collect more data,” Chiong says. Nevertheless, he adds, “it’s an issue we should keep checking in about,” particularly as researchers pursue technology able to treat mood disorders and other psychiatric conditions.

Meanwhile, implants are getting smarter, with artificial intelligence playing an ever-greater role, Chiong notes. “We’re talking about devices being developed now that can monitor someone’s brain function and make adjustments on the fly,” he says. Such AI-controlled implants may present ethical quandaries that previous interventions, such as pharmaceutical drugs, do not.

Winston Chiong

neuroethicist and member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences

Chiong offers an example: “We’re all familiar with alterations in our brain function from things that we ingest, whether it’s a pill or a cup of coffee,” he explains. “We might feel a little strange or act a certain way, but then we might think, ‘Well, I wouldn’t have acted that way normally – maybe it’s the medication or the caffeine.’” People may lack this intuition if an intelligent machine controls the dosage, he says. “Oftentimes, a patient may not even be aware of what the device is doing and when it’s active.” Such scenarios, Chiong says, raise questions about human agency and who – or what – is responsible if things go awry.

Ultimately, the rise of gene therapies and brain implants suggests the possibility of recasting parts of ourselves we once accepted as elemental or fixed. Given this new biological liberation, Chiong says, “we’ll face a choice we didn’t face before: Do we want to remain the way we are, or do we want to change?”

Great Power, Great Responsibility

The answer will impact not only the human self but also our societies. The genomic tweaks and neural tunings we choose to value, for instance, could shift social norms, ethicists say. Most Americans today would feel remiss if they did not correct poor vision, straighten their teeth, or vaccinate their kids. Will tomorrow’s citizens feel obligated to get cognition-boosting implants and edit their children’s genes to protect against asthma, cancer, or learning deficits?

Illustration: Mike McQuade

We might very well enjoy such gains. But the more we strive toward ideals of health or ability, ethicists warn, the less we may tolerate people who don’t meet them, whether by circumstance or choice. Some people with diagnoses of disability or disease, including dwarfism, deafness, autism, and even hemophilia, consider their conditions part of their identities and aren’t interested in cures, points out Jodi Halpern, MD, PhD, a professor of bioethics and of medical humanities in the UC Berkeley-UCSF Joint Medical Program. “We don’t want to be Luddites about humans changing what’s possible for themselves,” she says, “but we do want to appreciate the threats to human dignity and human diversity that can come from too much perfectionism.”

The specter of eugenics looms, as does the danger of exacerbating disparities in health and wealth. “All of these technologies are landing right now in a society with horrible problems of increasing income inequality,” says Barbara Koenig, PhD ’88, the founding director of the UCSF Program in Bioethics. “Who’s going to be able to enhance their children? It’s going to be the people who already are sending their children to private school and paying thousands of dollars for SAT tutors.” Similarly, if a future therapy lowers one’s risk of diabetes or susceptibility to smog, “who gets access to that?” asks Sara Ackerman, PhD, MPH, a medical anthropologist in Koenig’s program. “It may be the people who already live in neighborhoods with healthy food and clean air.”

Barbara Koenig

founding director of the UCSF Program in Bioethics

Of course, those are big ifs. Gene therapies and brain implants are still new frontiers; we can’t know for sure where they will lead. But ethicists and researchers alike agree: We don’t want to wait until the implications are upon us before we start grappling with them. As Doudna says, “We should be encouraging an open discussion: What are the pros and cons? What types of applications would be considered responsible? How do we regulate them? How do we pay for them? Who decides who gets to use them and when?”

Increasingly, social scientists like those in UCSF’s Program in Bioethics work alongside clinical investigators to help begin addressing such concerns – a practice Koenig refers to as embedded ethics. She and collaborators are also exploring ways to encourage and make use of public discourse. “There’s no road map for thinking about how you ethically translate these very foundational discoveries into the clinic,” she says. “You’re building the road map as you’re going.”

The question, then, is not whether we should go down the road toward genetic and neural self-augmentation. We already are. Rather, the decision we now face is how far we want to go and how we’ll get there.

This story is our story – of the future that awaits us and generations to come. It’s up to us to learn what we can about these emerging technologies – how they work, what they may be able to do, and the visions researchers have for them. We must consider their profound potential for good and ponder their possible dangers. We must think long and hard about the human qualities we value and what we would change if we could. And we must ask ourselves: Who do we want to be?

UCSF Magazine

Dive into the future of health in this special issue of UCSF Magazine.