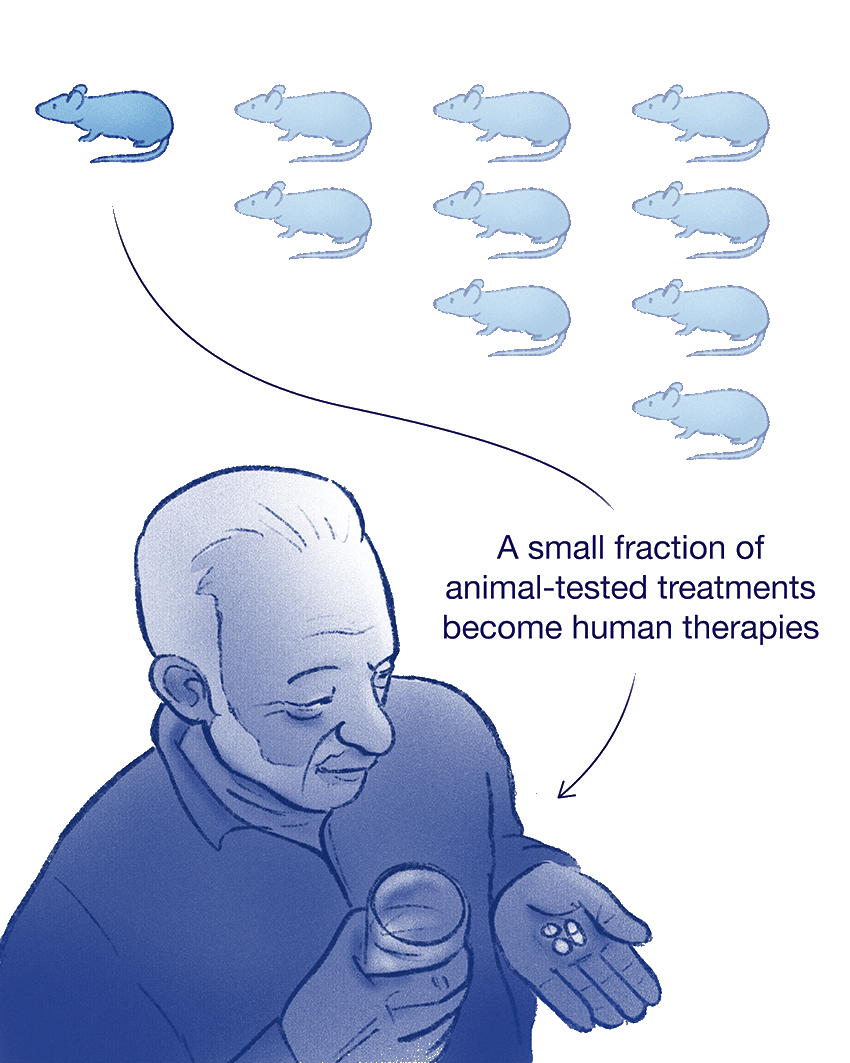

Before anyone pops a pill, researchers first have to show that the new medication is safe and effective — which requires testing, often starting in mice. But mouse models are just that — models — because nonhuman animals’ physiology isn’t an exact match for our own. It’s a monumental problem. Nine out of every 10 treatments that look promising in mice fail once they reach human clinical trials, driving the staggering cost of developing a new drug to an average of over a billion dollars.

There’s got to be a better way. Zev Gartner, PhD, is among the engineers at UC San Francisco trying to develop one.

professor of pharmaceutical chemistry

“We need improved models,” says Gartner, a professor of pharmaceutical chemistry. “Microphysiological systems are an attempt to address that by making a mini model of a human organ.”

These small-scale models mimic the function of human tissues or organs. The best-known example is “organs on a chip.” They look like computer chips — flat, rectangular wafers of silicon — but they contain cells derived from humans and are designed to simulate what whole organs do. For years, Gartner has been working on blueprints to build new and improved systems in his lab.

“It’s not a human organ,” Gartner says. “But it’s meant to do a much better job of replicating human physiology, ideally, by using the right cells and bringing some of the biophysical cues and tissue-to-tissue interactions together into a single device. We’re trying to generate an organ on a chip where the organ is the chip.”

“Organs on a chip” has emerged as shorthand for a suite of biomedical technologies that allow scientists to experiment on living human cells in new ways. They draw from advances in two fields. The physical hardware, the chip, comes from the semiconductor industry, which enables the fabrication of pliable strips of plastic and other materials with microscopic, hairline channels, integrated sensors, and data processing.

The second part — the biological circuitry, if you will — takes a page from stem-cell research, allowing scientists to precisely place or “print” cells onto the chips. Researchers use induced pluripotent stem cells, which renew themselves and can be turned into virtually any cell type. In a lung on a chip, for instance, scientists sandwich cells found in human lungs between two artificial chambers designed to mimic air flow and blood flow.

But these simplified models sometimes lose the plot: the cells don’t always behave correctly when they’re grown on plastic or silicone. One team researching tiny spheres of human breast tissue found that cancer drugs did one thing to cells grown flat on plastic dishes, then showed wildly different results when the exact same cells were grown with more complex, three-dimensional scaffolding that more closely simulates conditions in the body. Gartner and many others believe that the shortcomings of the simplified lab-grown models might be related to the chip itself.

“The goal is not to make a blood vessel supported on plastic,” Gartner says. “It’s to have different tissues in intimate contact in the same way that they are in the body.”

Why We Need Alternatives to Animal Models

Animal Models Often Fail

Animal physiology isn’t an exact match for our own. Nine out of every 10 treatments that look promising in studies of mice fail once they reach human clinical trials.

Organs on a Chip

To improve drug development, researchers are turning to organ-on-a-chip systems that recreate key aspects of human physiology using human stem cells.

Organoids

Engineers like Zev Gartner, PhD, are also building organoids — clusters of human cells — that could help them conduct research in ways that better predict how treatments will work in people.

Big picture, organs present some fundamental engineering challenges for anyone attempting to recreate them outside the body. Take the intestine, for example: a long, twisting tube lined with specialized epithelial cells that not only absorb nutrients but get stretched and convulsed with wave-like muscle contractions. The intestine also connects to other organ systems through nerves and capillaries flowing with blood.

The closer Gartner and his team get to mimicking these biophysical cues — the stress, pressure, and strain of intestinal function, along with the geometry and flexibility of real human tissue — the closer they might get to a drug testing strategy that predicts results in people far better than animal models.

Gartner recently devised a technique for constructing so-called intestinal organoids — free-standing clumps of cells about the width of a couple sheets of paper. He’s enabling the cells to form into tissues structured more or less as they are in the human body. To achieve this, his team adds another dimension: time.

“We would like to harness the ability of human stem cells and their progeny to self-organize effectively — to basically reboot human development in a dish,” says Gartner. “It’s an intact piece of human tissue that you can then use for studies.”

Moving Toward More Efficient Testing and Tailored Treatments

His research sits on the cutting edge of a much broader trend. With the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act of 1993, the NIH — the single largest supporter of biomedical research in the U.S. — expanded funding for developing new ways to reduce or replace animal studies. In 2024, the agency launched a new initiative to search for alternatives to traditional animal models. And in July 2025, the NIH announced that it would no longer fund new grants based solely on animal models.

Instead, the agency’s review process now prioritizes “human-based technologies,” including mathematical models, artificial intelligence, and microphysiological systems designed to mimic specific organs. The move follows the 2023 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Modernization Act 2.0, which also prioritizes nonanimal methods in research.

“They’re not saying ‘No more animal experiments,’” says Christopher Hernandez, PhD, a mechanical engineer who is the director of UCSF Health Innovations Via Engineering (HIVE). “But if you can prove efficacy with an organ on a chip or a computer simulation convincingly, the FDA will allow you to move forward with a new treatment.”

professor of orthopaedic surgery and director of UCSF Health Innovations Via Engineering (HIVE)

In the near term, Hernandez does not expect these federal initiatives to do away with animal models entirely. Rather, the idea is to expand scientists’ use of other models, then validate the results with animals as needed. This approach might ultimately reduce animal testing, improve efficiency in drug development, and lead to substantial savings in some cases. For example, Moderna, a biotech company best known for its vaccines, reported that using liver-on-a-chip technology instead of animal models enabled its scientists to screen dozens of potential drug formulations in 18 months for about $325,000 — work that might otherwise have taken five years and more than $5 million.

“You could maybe test a hundred things in your chip, and once you find something good, you try it in the animal,” Hernandez says. “It’s better for screening, and it’s potentially going to give us better cures faster.”

In 2023, Hernandez was tapped to lead HIVE, a home for UCSF engineers working to advance a variety of biomedical technologies. Gartner is among these faculty members, who hail from many schools and disciplines, including neurosurgery, dentistry, chemistry, and pharmacy. But they all use an engineering approach to understanding basic human biology and how diseases develop, with the goal of accelerating progress for a wide range of health problems. HIVE’s engineers use human cells in the lab to study infectious diseases like tuberculosis, chronic conditions like diabetes, and developmental processes like skin or tumor formation.

In his own lab, Hernandez, who is a professor of orthopaedic surgery, still pursues his longstanding interest: the properties of bones, the living, load-bearing, skeletal scaffolding that’s (usually!) inside the human body. His lab was the first to study how microbial communities in the gut influence bone mass and quality. Now, he’s working on dental biomaterials able to continuously release microbes that improve health.

One of his collaborators, Edward Hsiao, MD, PhD, specializes in the study of hormones and how they affect bone health. He’s focused on developing bone-on-a-chip systems. Bones don’t just provide structure; they also help regulate hormones, mineral levels, and energy metabolism. This makes a rare disease called heterotopic ossification — when bone tissue forms in muscle and other soft tissues where it’s not normally supposed to be — particularly difficult to study. Hsiao hopes to better understand how inflammation and other factors influence bone formation, with the goal of stopping or even reversing heterotopic ossification.

professor of medicine

To that end, Hsiao’s team is working on a human-cell-based device that models how bone interacts with immune cells and incorporates mechanical loading — physical stress on the bones.

“The skeletons of mice are very different from the skeletons of humans, even though they share many of the same cell types and gene pathways,” says Hsiao, who is UCSF’s Robert L. Kroc Professor of Rheumatic and Connective Tissue Diseases. “Being able to model human beings using human cells is really desirable.”

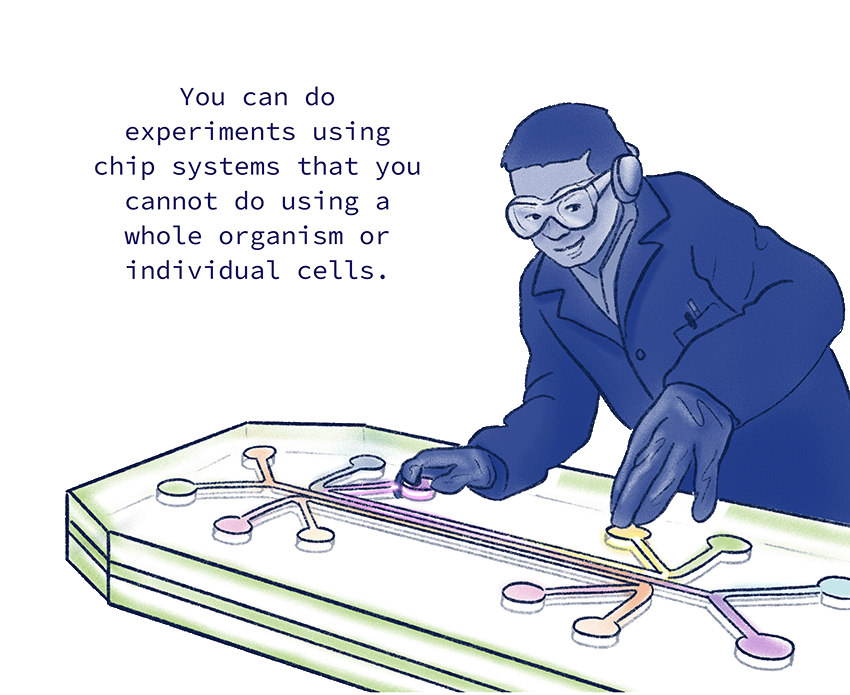

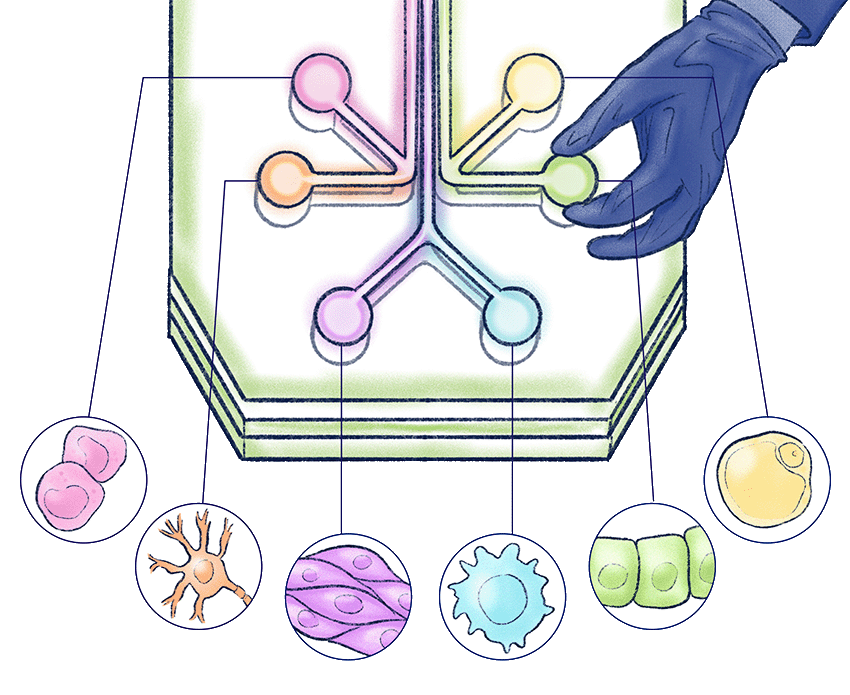

The simplified system basically allows Hsiao to operate like a sound engineer at a control board. The device has several chambers. One holds bone-forming stem cells. Another contains macrophages, immune cells that are critical for both triggering and resolving inflammation. The third is full of fat cells, also known as adipocytes.

“I can ask, ‘What happens if all of the media from the inflammatory chip goes into the bone stem cell chip?’” Hsiao says. Or he can tweak the knobs another way. “I could swap the two chips around and ask, ‘Okay, so then what is it about the adipocytes that’s actually affecting the immune cells?’ You can do experiments using chip systems that you cannot do using a whole organism or individual cells.”

Faster, More Flexible Experiments

Edward Hsiao, MD, PhD, is developing a bone-on-a-chip system that lets him operate like a sound engineer at a control board, precisely controlling how different kinds of human cells interact in one device.

“If he figures out how the cells are signaling each other, we can also find the best knob to turn with a pharmaceutical.” — Chris Hernandez, PhD, mechanical engineer and director of UCSF Health Innovations Via Engineering

The bone-on-a-chip model does not encompass everything we know about how human bones work in actual human bodies. But it has already allowed Hsiao’s team to tease out the specific effects of the macrophages in bone disorders and other diseases, like diabetes.

“If he figures out how the cells are signaling each other in a disease state,” Hernandez says, “we can also find the best knob to turn with a pharmaceutical.”

Going forward, Hsiao imagines that these systems could be personalized — say, allowing scientists to use a specific patient’s cells, then test a range of drugs to determine the most safe and effective treatment for that individual. Such highly tailored therapies offer obvious advantages over the status quo, especially for rare diseases involving multiple genetic drivers. Traditionally, a patient might have to try each potential treatment their physician suggests, one after another, to find out what works best for them.

“The new models provide an opportunity to really try to narrow things down, to identify what cocktail or single drug might be helpful,” Hsiao says. “It’s like a virtual clinical trial where you can test ideas with the patient’s own cells.”

Getting Closer to an Era of Made‑to‑Order Organs

One morning in early September of 2025, Gartner pulls up a series of images from his lab’s latest experiments. One image shows a magnified cross-section of the human intestine. The epithelium, the tightly packed cells that line the intestine, appears in yellow; the smooth muscles, the walls of organs, are in green.

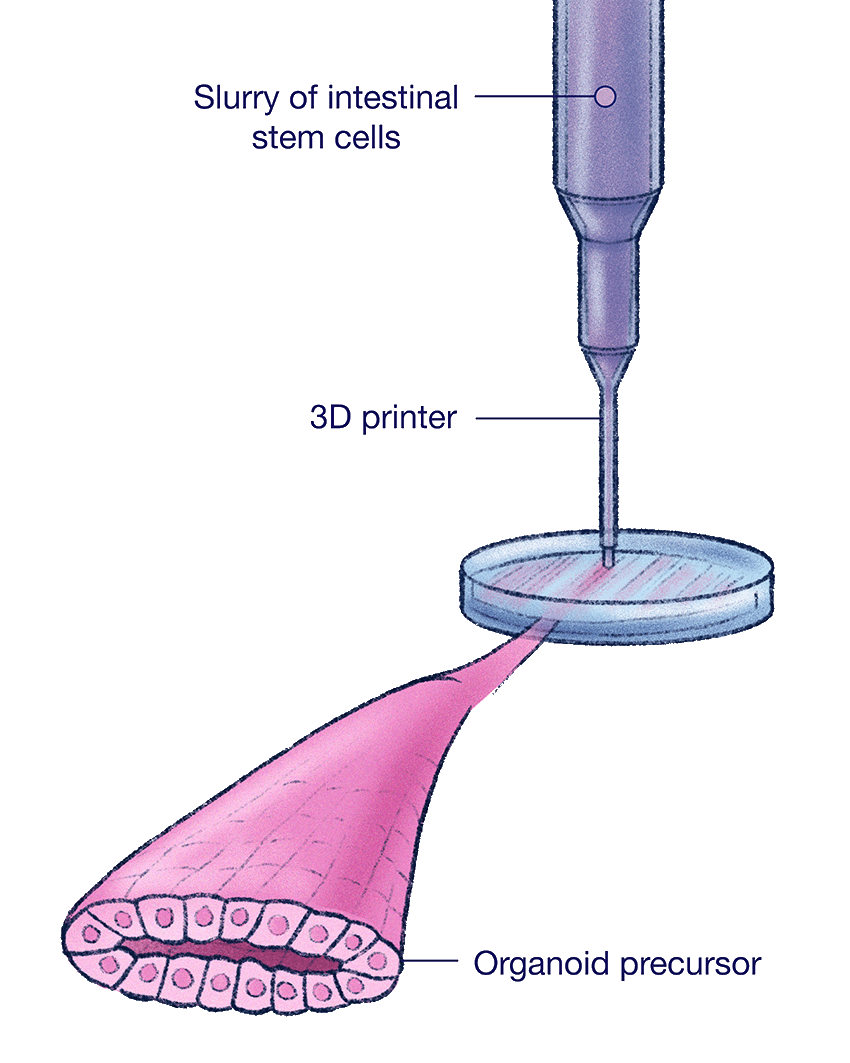

To create a human intestinal organoid, his team loads a liquid slurry of intestinal stem cells into a nozzle, then uses a fancy 3D printer to squirt them out like toothpaste. It doesn’t form a perfect tube. But it does define the cells into a rough outline — a tubular architecture resembling the digestive system. Then the researchers wait.

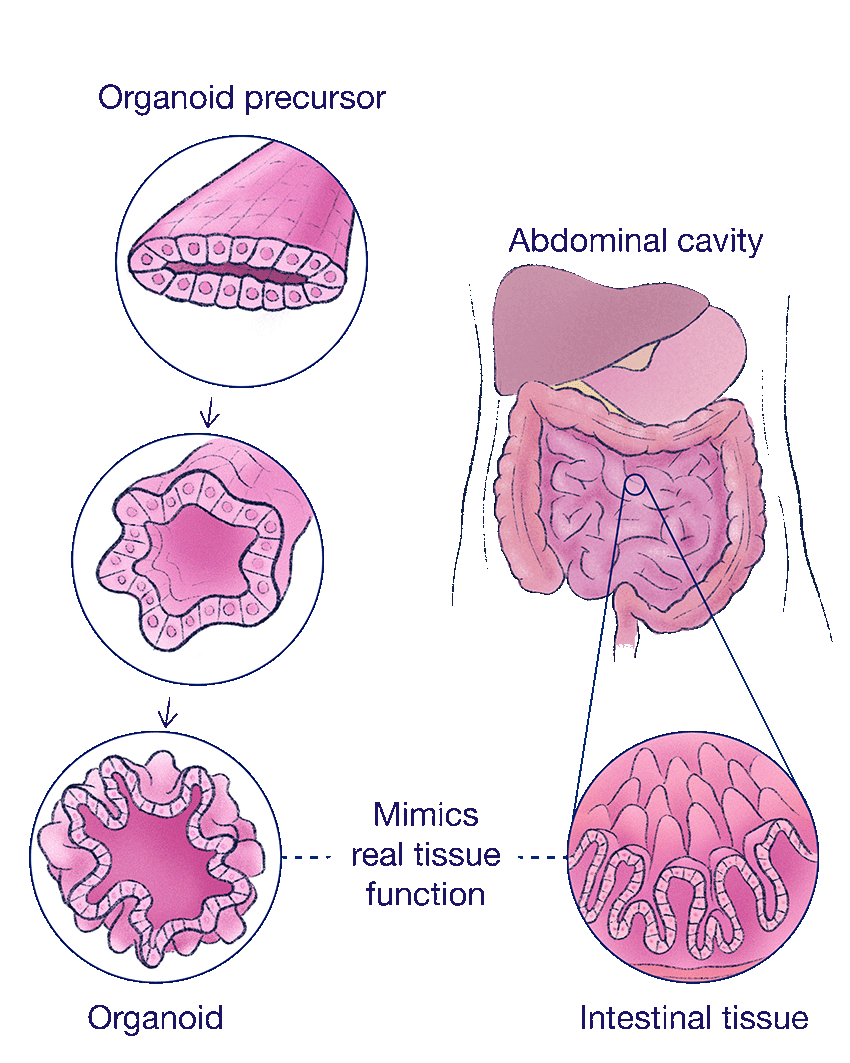

After a few days, the tissues meld into a more or less continuous segment. Eventually, little folds, lined with the yellow epithelial cells, start to wrinkle into shape.

“It’s not indistinguishable,” Gartner says, zooming out. “But it looks pretty similar, right?”

Side-by-side, the model resembles a human intestine. But what excites him most is the twitch.

“We think that’s the onset of smooth muscle contraction — the earliest event in the emergence of peristalsis,” Gartner says. It’s the involuntary movement in the intestine that moves food through the digestive system. His team has been trying to add another layer: the infrastructure that sits underneath the epithelium and takes in nutrients. It holds the tissue together and regulates the immune system, too.

“That’s sort of like the plumbing of the city,” he says. “If San Francisco is just a bunch of skyscrapers that ended at the walls of the buildings, nothing would work, right? You need electricity, clean water, transportation, sewer, and communication systems.

“And in tissues, it’s the same. Like, if you really want an organ to come to life, you better add the stroma, the tissue that sits underneath the epithelium,” he says. “That’s where we want to go with this.”

Where This Technology Is Headed

3D Printing Cellular Architecture

To create a human intestinal organoid, Gartner's team loads a slurry of intestinal stem cells into a nozzle, then uses a fancy 3D printer to squirt them out like toothpaste.

Mirroring the Function of Human Cells

Researchers are making progress toward replicating the structure and function of real organs. Over time, the organoids begin to mimic real intestinal tissue, developing folds lined with nutrient-absorbing epithelial cells.

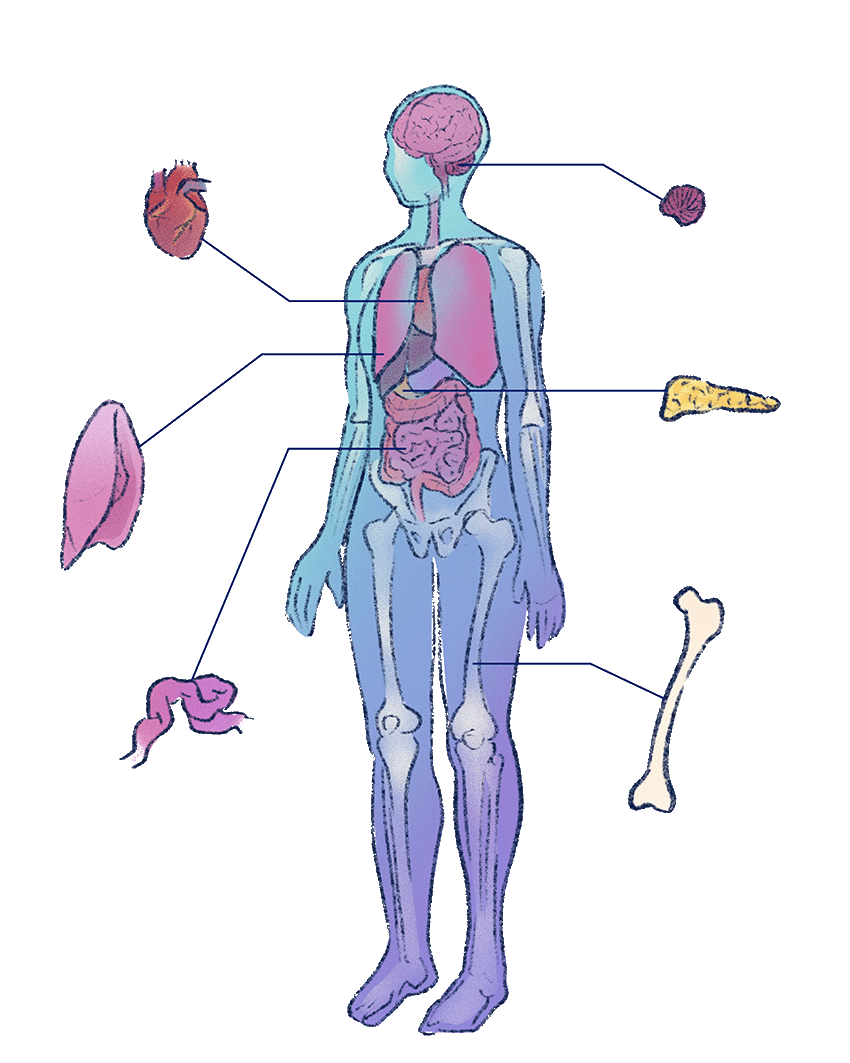

Future of Healing?

This kind of research could lead to a future with more effective and ethical alternatives to animal testing — and maybe new ways to repair or replace damaged organs.

Gartner knows it sounds like science fiction now, but he hopes his research might lead to a real-world future where microphysiological systems do more than create an effective, ethical alternative to animal testing. As scientists make more realistic, self-supporting human tissue, the technology could lead to a practical way to regenerate and repair tissues inside a patient’s body. Maybe one day it could even replace damaged organs.

That sounds far off, but Gartner and others are taking steps in this direction. He’s part of a team that recently received a $5.7 million NIH grant to improve oral tissue grafts, which currently fail about a quarter of the time. Gartner is working to adapt his experimental tissues, which include blood vessel networks, into living dental grafts — ones that closely resemble the patient’s own tissues and that restore essential functions of the mouth, like speaking and eating.

“We’re opening up new dimensions of this larger goal of building human physiology in a dish,” Gartner says. “It’s no longer just a tissue that’s useful for testing drugs or discovering new disease targets. It’s moving toward something that you can start to put into people.”