In early April 2020, a few weeks after San Francisco officials issued their first stay-at-home order of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cliff Morrison, MSM, MSN, showed up for work at one of the behavioral health facilities he administers. He had barely begun his day when he suddenly spiked a temperature of 101°F. He started packing his things to go home but quickly felt so exhausted he had to lie down in his office. His primary care doctor at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital (ZSFG) diagnosed him with COVID-19 that same afternoon.

When it came to pandemics, Morrison thought he’d seen the worst already. In the early 1980s, as a psychiatric nurse at ZSFG, he was on the wards as the first patients fell ill and died of what came to be known as HIV/AIDS. So much fear and uncertainty accompanied the disease that doctors treated AIDS patients largely in isolation, which upset Morrison. In 1983, he helped ZSFG open the first dedicated inpatient AIDS unit in the country, and it went on to become a global model for compassionate treatment of patients hospitalized with AIDS.

After his COVID-19 diagnosis, Morrison, who is 70, isolated at home with his two cats. He expected to return to work after two or three weeks. But a month later, he still had severe headaches, digestive troubles, extreme fatigue, and memory lapses. “Everybody kept saying to me, ‘This is a 14- to 19-day deal,’” Morrison remembers. “I was starting to wonder if I had lost my mind.”

That’s when Morrison’s doctor told him about a study that UC San Francisco researchers had launched at ZSFG to look into the long-term effects of COVID infection. Morrison, who knew many of the research staff from his days as an HIV nurse, called and signed himself up immediately. He wanted to contribute to science, certainly – but he also wanted answers about what exactly was happening to him. “It was extremely reassuring and made me feel so much better, that at least someone was interested in what was going on,” he says.

Though it wasn’t widely known at the time, Morrison wasn’t the only person still struggling with COVID long after most experts expected them to get better. Consensus had it that mild to moderate infections cleared the body within a few weeks, so many clinicians and scientists were skeptical of claims like Morrison’s of ongoing symptoms. Some people spoke publicly about their problems only to find themselves dismissed as having anxiety, or maybe lockdown-induced hysteria. It wasn’t until December 2020 that federal health officials declared “long COVID” real and worthy of being taken seriously.

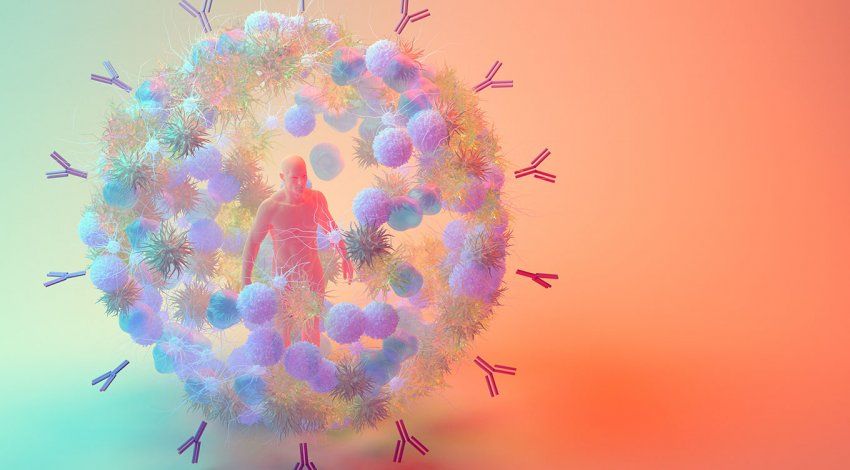

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), anywhere from 10% to 30% of people infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, experience persistent and potentially incapacitating complications that last far longer than their original illness. With nearly 50 million known COVID cases in the U.S. alone, that may already amount to as many as 14 million people experiencing long-term effects. And the ranks of those with long COVID are still growing, particularly among the unvaccinated, who are thought to be at higher risk for developing long-term symptoms. The result may be its own public health crisis – compounding the original one – with at least some patients unable to live normally for weeks or months after their original illness.

But in the early weeks of the U.S. outbreak of COVID-19, long COVID was practically unheard of. The researchers who started the UCSF study, which they named Long-term Impact of Infection with Novel Coronavirus (LIINC), did so without entirely knowing what they were even looking for. While most of the medical community was still focused – as it should have been – on preventing and treating the most severe cases of COVID-19, “we were really the only group that was focused on what happens after the acute phase,” says Michael Peluso, MD, one of the study’s leaders. For many patients with lingering COVID symptoms, LIINC was also the first place they found validation that they weren’t imagining things.

Morrison was one of the earliest of the more than 400 participants to enroll in LIINC, which includes a diverse assortment of patients. Some of them survived knock-down, drag-out cases of COVID, while many barely noticed that they were ill in the first place. LIINC gave UCSF researchers a uniquely broad and early window into how people in different circumstances experienced infection and recovery. And the data from those patients will help illuminate how SARS-CoV-2 infiltrates the heart, lungs, brain, and other critical organs – and hopefully start to explain how it continues to wreak havoc on the body months after the original infection is gone.

About a month before Morrison first came down with COVID-19, Peluso was seeing patients at ZSFG’s infectious disease clinic. At the time, he was a research fellow working with people with HIV. For months, Peluso had been aware of the looming threat that COVID-19 represented, but it didn’t truly hit him until March 5, when he heard that San Francisco authorities had detected community spread of the disease. Peluso called his mentor, Steven Deeks, MD ’90, who had just flown back to San Francisco after the second leg of a business trip had been abruptly canceled. “Something is happening, and I want to be ready to work on this from a scientific perspective,” Peluso remembers telling him.

Since 2017, Peluso and Deeks had been working together on the SCOPE study, a long-term research project that aims to reveal how HIV infection persists and affects the body despite treatment. Deeks – a professor of medicine at UCSF and a member of ZSFG’s Division of HIV, Infectious Diseases, and Global Medicine – had co-founded the SCOPE study back in 2000. For more than 20 years, the SCOPE team has regularly collected blood and tissue samples from a cadre of volunteers with and without HIV. This ongoing relationship with participants and an ever-growing library of their biological specimens have helped researchers worldwide investigate how to thwart the virus.

Michael Peluso, MD, is one of the leaders of UCSF’s LIINC study. Photo: Monika Deswal

Peluso and Deeks knew they couldn’t do much to stem the tide of acutely ill COVID patients who were about to flood intensive care units at hospitals all over San Francisco. Their expertise was not in Hot Zone-style virus hunting or emergency respiratory medicine, but in deep, careful investigations that unfold over the course of decades. So Peluso wondered if they could take the same systems they’d developed to follow patients with HIV over many years and use them to trace how the immune system responds in the months following a SARS-CoV-2 infection. “I thought it was brilliant,” Deeks recalls of the idea. “It was the obvious thing to do.”

Peluso spent the next two weeks, as the city locked down around him, scraping together a research proposal from his living room. He sought help over Zoom from colleagues, including UCSF epidemiologists Dan Kelly, MD, MPH, and Jeffrey Martin, MD, MPH. Peluso didn’t know yet that he was designing one of the first research studies to address long COVID. He only knew he wanted to study the body’s long-term response to the virus by measuring antibodies and other signs of immune activity. He decided to collect blood and saliva from recovering COVID patients beginning 28 days after their acute illness ended – the soonest, according to UCSF guidelines at the time, that he was allowed to see them in the research clinic. Some of the samples would be tested for levels of COVID-specific antibodies, and the rest would be stockpiled in the hope that they could eventually help answer questions researchers hadn’t yet thought of.

On April 21, less than seven weeks after conceiving the study, Peluso enrolled the first participant. Over the next six weeks, the team recruited 70 recovering COVID patients who represented the ethnic diversity of the Bay Area and ranged in age from 18 to 85. Unlike many studies at the time, which focused on patients who had been hospitalized with COVID, LIINC primarily recruited recovering patients who never fell critically ill. That would make it more likely that any lasting symptoms they reported were caused by the novel coronavirus rather than by the many physical, mental, and emotional stresses that follow treatment in an ICU.

Before the scientists could dig into the data, though, they had to scramble to find somewhere to store the hundreds of vials of biological material they were suddenly collecting. Though he normally focuses on curing HIV, Timothy Henrich, MD, offered to turn his research facilities into an ad-hoc sample processing lab. Henrich had to buy several new freezers to hold the samples that were quickly accumulating from LIINC participants. “I had staff members there for hours every day just processing and storing cells and plasma and serum and saliva,” Henrich recalls.

Even though the LIINC team hadn’t ironed out all of its research questions yet, banking these specimens beginning in April created a kind of scientific time capsule. As new questions emerged, they figured, having samples on hand from the weeks immediately following participants’ acute COVID infection would prepare them to launch investigations at the drop of a hat. That’s what had happened with SCOPE, as doctors treating patients with HIV encountered new symptoms and tested new treatment strategies. “Over 20 years, we’ve had maybe 10 new areas of investigation pop up, and SCOPE has changed on a dime to help answer those questions,” Deeks says.

Still, putting so many eggs into the post-COVID basket was a bit of a gamble, admits Peluso. What if COVID had been like the common cold or flu after all, and any symptoms of a mild case invariably dissipated within a few weeks? That was the going wisdom at the time, which was why Peluso planned to focus on how the body built immunity after kicking a COVID infection. “We were expecting that people would feel totally fine, and we would just be measuring how their antibodies changed over time,” he explains. But as his patients would soon help him discover, recovering from COVID wasn’t going to be as straightforward as had been assumed.

María Milián, a 69-year-old retired cancer researcher, fell ill in late June 2020, after her brother visited from Arizona. Milián has multiple sclerosis (MS), a degenerative neurological disorder, but she could tell that this was different from anything she’d experienced with that disease. For three weeks she felt deathly tired, she hurt all over, she barely ate, and she couldn’t smell or taste anything. Her vision blurred, and her arms and legs were tingly; she saw flashing lights and numbers behind her eyelids when she tried to sleep.

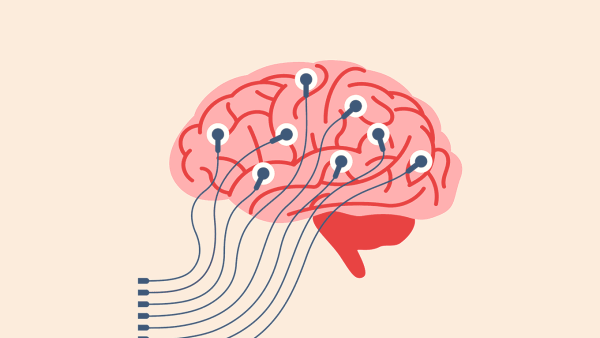

Milián was still having trouble concentrating and remembering things a couple of months after her positive COVID test. She enrolled in LIINC, but she wondered if scientists there would simply chalk up her brain fog to MS. Instead, she says, Peluso and the rest of the team listened with interest and told her they wanted to track whether her neurological symptoms got better or worse over time. “They took seriously that I had this brain thing that I didn’t understand,” she says.

And there were reports of other conditions from other patients: sleep problems, dizziness, anxiety, and depression. Some had shortness of breath and chest pain that stuck around for weeks – months, even – after the active viral infection was gone. Peluso and Deeks realized they could use the seat-of-the-pants nature of their study to good advantage if they started polling LIINC participants about symptoms the investigation hadn’t originally accounted for. It was much like how SCOPE had shifted over the years to adapt to new information, but instead of happening over decades, LIINC was changing from week to week. “We had nightly meetings between our epidemiology team, our clinical research team, and an army of volunteer medical students,” says Peluso. These meetings often lasted four or five hours; Peluso sometimes took part in them from his exercise bike.

When brain fog emerged as one of the most common and frightening symptoms, the team turned to neurologist Joanna Hellmuth, MD, MHS. She’d spent years at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center studying how HIV could compromise cognition in a strikingly similar way. In November 2020, Hellmuth, who is also an assistant professor at the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences, started recruiting LIINC patients struggling with brain fog into a specialized neurological substudy. She asked participants to help her understand their fogginess: Was it confusion? Attention problems? Memory lapses? Then she administered cognitive and other neurological tests to quantify the problems and try to ferret out their cause. Hellmuth also started running experiments on samples of blood and cerebrospinal fluid she collected from her set of volunteers. That allowed her to hunt for patterns in who experienced brain fog, when it happened, and for how long.

As the pandemic has continued, LIINC has spun off similar substudies in cardiology, pulmonology, hepatology, and even sleep medicine. That all of these specialties can draw from the same centralized group of post-COVID patients has allowed investigators to ramp up new studies relatively quickly. “If we didn’t have that infrastructure, everyone would be working in their silos,” trying to recruit volunteers from scratch, says Mandana Khalili, MD, MAS ’05, a UCSF professor of medicine and chief of clinical hepatology at ZSFG who is studying COVID’s effects on patients with liver disease. “But leveraging that existing infrastructure is leading to what we call a team science effect.”

Overall, Peluso and others have found, most long COVID patients are gradually improving. While roughly half of previously infected LIINC participants still have some symptoms after four to eight months, those symptoms have been debilitating for fewer than 5%. For Milián, recovery has been bumpy and nonlinear, but she’s getting there. Her fatigue and brain fog reared back up after she was vaccinated in February 2021, but these days she has enough energy and focus to attend virtual yoga classes and work in her garden again.

Morrison doesn’t feel fully recovered yet, but he does think he’s learning to cope better with his ups and downs. Meanwhile, the data collected through LIINC and its substudies are turning up clues that could prove valuable for helping long COVID patients like him. The team has realized, for example, that whether someone suffers aftereffects from an acute COVID infection doesn’t necessarily depend on how severe the original illness was. While some people are slow to bounce back after their initial, excruciating illness – but eventually do – others are largely asymptomatic during the acute phase but have new and puzzling problems pop up some time after that.

The LIINC team has found some indications that people with long COVID have higher inflammation levels than people who were back to normal four months after their infection. That could mean that some of the more protracted symptoms are related to an aggressive immune response. The virus can damage bodily tissues while it’s active, which could certainly cause health problems down the line – another potential culprit. Even once SARS-CoV-2 stops replicating, scientists have found, viral proteins continue to litter the body like shrapnel in a wound. Social and economic factors also seem to tip the scales, with early evidence indicating that people from underserved communities may be more likely to experience long-term problems. But as far as explaining what causes long COVID or how to treat it, says Peluso, “none of these are a slam dunk.”

The search for answers will soon get a boost from the NIH’s Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) initiative. The four-year effort will enlist researchers at more than 30 institutions to amass data from tens of thousands of long COVID patients across the country. “The diversity of symptoms and presentations leads us to believe that long COVID is not just one condition,” said retiring NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, in September, when he announced $470 million in funding to assemble the research consortium. “The only way, therefore, that we’re going to sort this out is with very large studies that collect lots and lots of data about symptoms, physical findings, and laboratory measures.”

If that sounds familiar, it’s because Peluso and the rest of the LIINC team have been doing just that ever since March 2020. That’s one reason RECOVER leaders sought their help in developing research protocols that will be applied across the country. It makes Peluso optimistic that he and other physicians will soon have better answers for long COVID patients and more ways to help them. The sudden scientific interest in viruses due to the pandemic could also shed light on other illnesses possibly triggered by viral infections, such as myalgic encephalomyelitis (formerly called chronic fatigue syndrome).

Peluso, now an assistant adjunct professor of medicine at UCSF, still spends at least a few minutes chatting with study participants every time they visit. “You get to know people really well, and you’re invested in their well-being,” he says. For Milián, who didn’t know anyone else struggling with long COVID while she was under lockdown, that has been one of the biggest benefits of participating in the study. “What helped was that there was actual contact – seeing people and talking about what was ailing me,” she says. She could ask whether other patients had experienced a particularly confusing symptom and hear that Peluso and his colleagues were already trying to get to the bottom of it.

“And then that kind of reassured me that I’ll get better,” Milián says. “It’ll be okay.”