Rapidly Responding to Long COVID

Since the early months of the pandemic, physicians throughout UCSF have pitched in to help support hundreds of long COVID patients.

Coordinated Care

UCSF’s OPTIMAL clinic is a one-stop outpatient center for patients recovering from COVID. After pulmonologists assess their patients’ needs in the clinic, they can immediately refer them to colleagues in physical therapy, psychiatry, integrative medicine, and other specialties. By streamlining this process, clinic founder Lekshmi Santhosh, MD, MAEd, hoped to take some of the burden off post-COVID patients and their families to coordinate their own care. That’s especially important for survivors who have already been through the wringer in the ICU.

Santhosh treated some of these same patients when they were intubated and unresponsive. “Seeing those folks in clinic afterward is so powerful that often both of us are crying,” she says. “There were many times [in the ICU] when we thought they would not survive.”

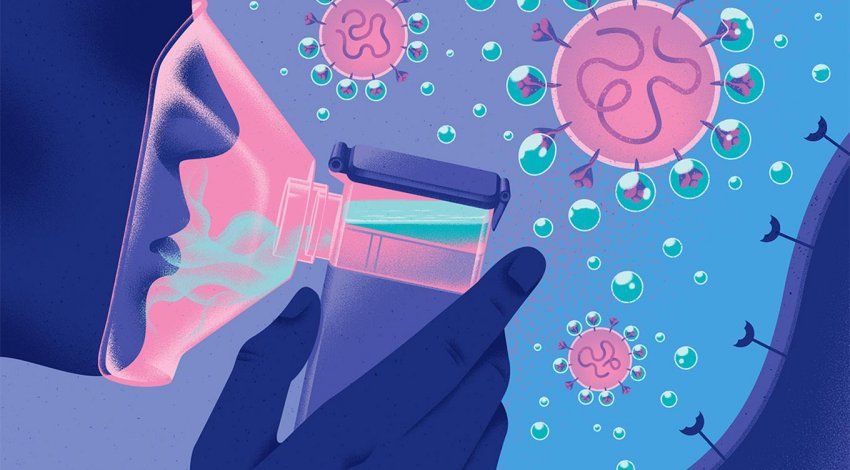

Sniff Test

An inability to smell is one of the best-known early indicators of a SARS-CoV-2 infection – and the symptom that seems to stick around the longest. In the clinic of ear, nose, and throat specialist Patricia Loftus, MD, patients who are struggling with smell loss take a 40-question scent identification test – basically a scientific scratch-and-sniff activity – to quantify their degree of impairment. She then prescribes a regimen of smelling essential oils and other aromatic substances to help them gradually retrain their damaged olfactory nerves.

The good news: About 75% of people who lose their sense of smell seem to recover it within about four weeks. By six months, the recovery rate improves to about 95%. Loftus hopes the pandemic will spotlight smell loss, which can also happen with age or as a result of other diseases. “If we can find better treatment,” she says, “it can definitely be used across the board.”

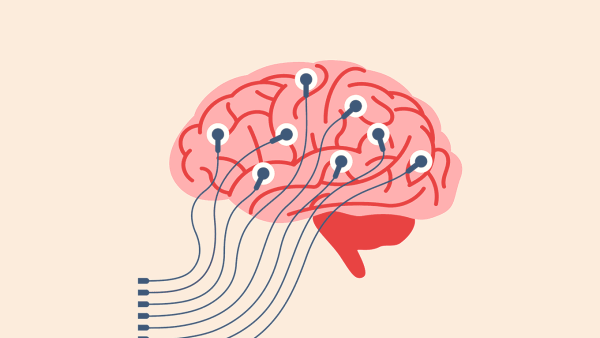

Investigating the Brain

Several weeks after the LIINC study got started, neurologist Joanna Hellmuth, MD, MHS, started seeing participants who were complaining of headaches and memory problems. Post-COVID patients as young as 17 were feeling confused and distracted and were unusually slow to retrieve names or find the right word on the tip of their tongue. In many cases, doctors had already dismissed the symptoms as the result of stress or sleep deprivation. But they sounded familiar to Hellmuth: “The cognitive syndrome we’re seeing with COVID is almost exactly the same as what we see with HIV,” she says.

Many physicians don’t know that viral infections can be associated with cognitive disorders, explains Hellmuth. But the phenomenon is well documented, even if it remains poorly understood. To try to change that, Hellmuth is collecting spinal fluid and running neurological tests on post-COVID patients who report cognitive symptoms. She hopes to learn what’s physiologically responsible – inflammation? blood vessel damage? – in the hope of finding ways to alleviate the issues.

If nothing else, Hellmuth hopes the data she’s collecting will help validate her patients’ experiences. Anxiety over not being believed only compounds their struggles, she says. “If patients tell us something’s going on with their bodies, let’s trust them,” she says. “I’m hoping this pandemic will bring some humility to medicine and bring to light the fact that viruses can do this.”

Group Therapy

As early as April 2020, Meghan Jobson, MD, PhD, started hearing from patie-nts with long COVID symptoms. Their toes were numb, they were paralyzed by depression, their ears wouldn’t stop ringing, they had no sense of taste. “I was like, I don’t know what to do for these people. We didn’t know anything,” remembers Jobson. But she did know some tactics for coping with ongoing medical uncertainty.

Jobson, a UCSF attending physician, joined forces with neurologist Juliet Morgan, MD, chief resident for education in the UCSF adult psychiatry program. Together, they organized a virtual integrative medicine skills group to support patients recovering from COVID. They started meeting over video once a week with about a dozen patients. The physicians share nutrition guidance, mind-body exercises, and mindfulness practices that have been shown to reduce stress and inflammation. With no solid answers yet about long COVID, their goal is to guide patients toward these evidence-based general wellness strategies.

The groups have also allowed long COVID patients to share their struggles and successes with each other. “A lot of the pain of long COVID is feeling misunderstood, invalidated, tossed aside,” says Morgan. “This gave patients a place to come together and hear that this is real and that they’re not alone.”