Picture a heart attack patient. If you’re thinking of the statistical average, this patient is likely a man over 65, is a smoker and on the heavier side, likes his steak and hamburgers. But this story is about a different type of heart attack patient: They’re slim and under 50, don’t smoke, are vegetarian. They’re also South Asian.

The pattern of cardiovascular disease in South Asians is striking and mysterious: Globally, people of South Asian descent represent 60% of heart disease patients, despite making up just 25% of the population. And while the average age of a first heart attack in the U.S. is 65 for men and 72 for women, half of heart attacks among South Asians occur before age 50.

Many South Asians develop the disease at lower body weights and younger ages, often without traditional risk factors like smoking that are seen in other groups. That means their vulnerability may be invisible to standard screening. These paradoxes led Alka Kanaya, MD ’95, a professor of general internal medicine, to launch the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America study (MASALA) at UC San Francisco in 2006.

“The big ‘why’ question had not been answered,” she says. “That was the impetus for wanting to do this work, to fill that gap.”

For Kanaya, that ‘why’ question is both scientific and personal. If you ask her about her connections to heart disease, she ticks them off steadily on several fingers: Her grandfather died from diabetes and heart failure. A cousin of her husband’s had a massive heart attack at 49 and died a few years later. A close friend’s brother-in-law had a heart attack at 48 and is now permanently disabled.

“I have many, many stories close to home,” she says. “If you ask any South Asian person, it’s one degree of separation between them and somebody who’s had an early and unexpected heart attack.”

MASALA — the study’s acronym is a Hindi word meaning a blend of spices — is the first and longest-running study tracking South Asians’ health over time. The effort has now expanded beyond UCSF to include researchers at Northwestern University and New York University, with more than 2,300 volunteers now participating in the Bay Area, Chicago, and New York City.

Their work over the past two decades is making the invisible visible, highlighting the risks that hide inside South Asian bodies and are too often missed by screening guidelines designed using data from other populations.

The Fat You Can’t See

One of MASALA’s most intriguing findings is about “hidden fat” — fat stored inside our muscles and livers and around the body’s other internal organs. This type, also known as visceral fat, dwells deep in the abdomen; high amounts distend the stomach and create what’s referred to as an apple-shaped body. Unlike subcutaneous fat, which sits just under the skin and is soft and pinchable, visceral type can’t be felt from the outside. But it’s dangerous.

In fact, more so than subcutaneous fat, the visceral variety is strongly associated with heart disease and type 2 diabetes. When fat accumulates inside the liver, it can cause scarring and even liver cancer. Normally, visceral fat is associated with obesity, but the MASALA researchers found that many South Asians have it even at normal body weights.

Genetics largely determine where we store fat, Kanaya says, but lifestyle could play a role as well. In non-South Asian populations, weight loss and regular exercise have been shown to reduce visceral fat deposits. The MASALA team is currently looking at known genetic causes for South Asians’ atypical fat storage pattern and is exploring whether participants’ diets or other lifestyle behaviors may contribute to it.

It’s likely that other aspects of South Asians’ increased risk of heart disease are due to a mix of nature and nurture, Kanaya says. Her team’s findings point to both biological and cultural underpinnings of disease.

For many participants, MASALA offers medical testing not available elsewhere, as well as new ways of thinking about their own health.

One long-time participant, for example, has made several lifestyle changes since joining the study almost two decades ago — though he almost didn’t sign up.

“My initial reaction was, I don’t think I’m interested,” says the participant, who works as an engineer. “I just don’t want to find out anything that I need to worry about.”

His family doctor convinced him otherwise, and now he’s glad he joined. The scans and bloodwork didn’t turn up anything worrisome, but he’s learned a lot about heart health and how diet and exercise could lower his risk.

Traditional Indian cuisine is often heavy in carbohydrates and fried foods, but he can’t remember the last time he had his beloved bhajis, battered and fried vegetables also known as pakora. These days, he and his wife, who is also a study participant, eat a lot of vegetables but eschew the deep fryer. He also got into the exercise habit many years ago and still works out several times a week.

What Standard Screenings Miss

South Asians who don’t have access to the detailed screenings available through studies like MASALA might not realize that they are at high risk for heart disease. And, worryingly, they might slip through the cracks of traditional, less intensive screenings at their doctors’ offices.

Well-known risk factors for heart disease include smoking, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol levels. While South Asians aren’t immune to these classic risk factors, the MASALA team has also found less obvious factors that could contribute to their heart disease risk. Compared to white, Chinese, and Hispanic people, South Asians have higher levels in their blood of a molecule known as lipoprotein A. This molecule’s action is similar to that of LDL cholesterol, or “bad” cholesterol. High levels are largely genetically determined and are linked to increased heart disease risk. But it’s not part of standard cholesterol panels, making it another invisible risk. South Asian patients — or their doctors — would have to specially request the test.

Lipoprotein A is not the only biological difference the team discovered. They also found that South Asians are more prone to a less common variant of type 2 diabetes, one in which pancreatic beta cells don’t produce insulin as they should. This kind of type 2 diabetes develops at a younger age than other forms of the disease, and it is also more likely to lead to atherosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries.

Before MASALA, many of these differences were unrecognized by the medical system. South Asians were often lumped together with East Asians in U.S. health studies, their specific risks obscured by aggregation. Screening guidelines used the same body mass index thresholds for all populations. A South Asian person could walk into a doctor’s office at a BMI of 24 — a technically normal body weight — already at risk for diabetes and walk out without a screening test because they didn’t meet the typical threshold.

When Discoveries Change the Rules

Now, clinical guidelines are catching up to these findings. MASALA’s data helped inform the American Diabetes Association’s 2015 decision to lower its diabetes screening threshold for Asian Americans from a BMI of 25 or higher to 23 or higher, catching cases that would have been missed under the old guidelines. MASALA data has also impacted treatment recommendations by the American Heart Association.

“We’re working to provide evidence to guide health professionals and screening recommendations so that we can have better care and change people’s health trajectories,” Kanaya says.

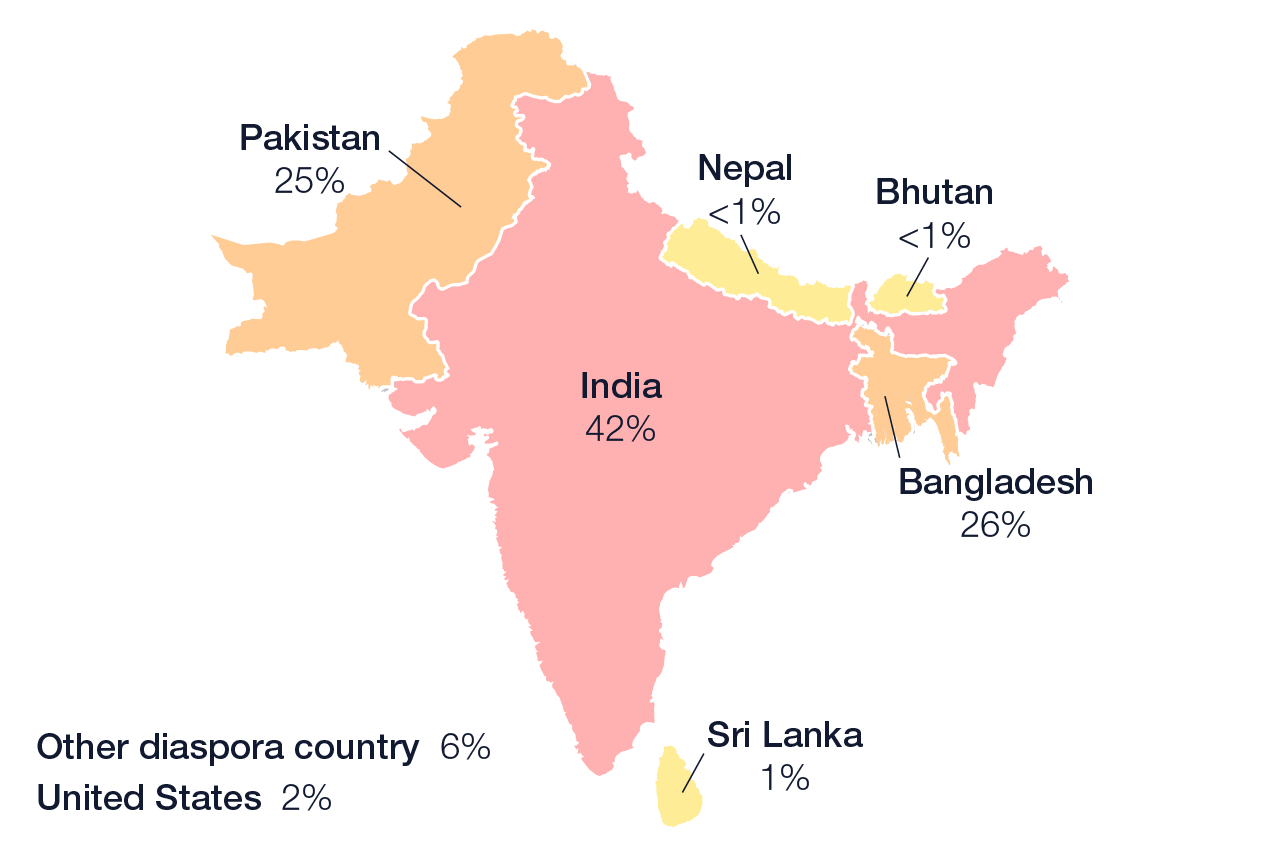

The work has also revealed yet another layer of invisibility within the South Asian population itself. While most of MASALA’s initial participants were Indian, the study has recently enrolled more Pakistanis and Bangladeshis. Despite the three populations being genetically very similar to each other, the researchers discovered that Bangladeshis have even higher rates of diabetes and hypertension than do Indians, while Pakistanis lie in between. The team is now sifting through socioeconomic and lifestyle data to try to understand the reasons for those differences. Due to late-20th-century immigration policies, Indians who emigrated to the U.S. tended to be more educated and economically advantaged than other immigrant populations; today, Indian Americans have the highest median household income of all population groups in the country. Pakistani and Bangladeshi immigrants tend to have lower incomes, and socioeconomic status itself is a risk factor for heart disease.

MASALA Study Participants by Country of Birth

These findings matter for more than just the South Asian community. A 2019 study found that less than 0.2% of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) budget went to studies of Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander populations — even though they make up more than 6% of the U.S. population. In recent years, the NIH has launched several other large health studies of Asian Americans, Kanaya says, influenced in part by MASALA’s success and her team’s advocacy.

Separating South Asians from East Asians allowed the scientists to make key findings, such as those about visceral fat and lipoprotein A, and they hope that further segmenting the participants in the study will lead to even more insights that could improve everyone’s health.

“Aggregating all Asians together obscures critical differences,” Kanaya says. “Having representation of different groups in health studies is so important — otherwise we’re not getting the full picture. What we learn from MASALA is not only for South Asians. We will understand how to better prevent and treat heart disease in everybody.”