The End of Infertility Is in Sight

Fertility expert Marcelle Cedars discusses the future of reproductive medicine.

Illustration: Abigail Goh

Advances in medicine and public health have dramatically extended the human lifespan. Our hearts, lungs, and other vital organs now last 79 years on average. For women, however, the ovaries – which stop functioning at an average 51 years – remain a stubborn exception. That may soon change, says fertility expert Marcelle Cedars, MD, during a conversation on the future of reproductive medicine.

What causes the ovary to decline earlier than other organs?

There are two aspects. One is qualitative. As a woman ages, the quality of her eggs – meaning their capacity to make a healthy baby – declines. We understand very little about what causes this decline. If we understood that process better, we could dramatically impact fertility success rates.

Marcelle Cedars is the Laura Ambroseno and Raffaele Savi Family Presidential Professor. She directs the UCSF Center for Reproductive Health and the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology. Photo: Steve Babuljak

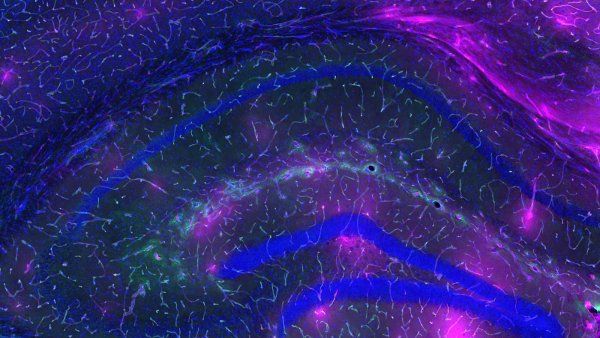

The other aspect is quantitative. Women are born with a finite number of eggs, and they lose those eggs throughout their lifetime. In fact, that rapid decline in egg numbers starts even before birth. There’s a peak in utero of five to six million eggs. At birth, a woman has only about 1.5 million eggs; at the time of puberty, about 500,000. Through genetics research, we’re learning that the rate of this decline – and the variability from woman to woman – is largely driven by one’s genes.

So my fertility window is, in some sense, predetermined?

Exactly. But what if we could use your genetics and other biological data to understand your unique fertility risks and develop therapies specifically for you – or for groups of women like you? This approach is called precision medicine. It has made a huge impact in the world of cancer in terms of improving survival rates. But in the field of reproductive health, precision medicine is still in its infancy.

Do you think future therapies will allow more women to conceive children later in life without in vitro fertilization?

Potentially. If we can pinpoint the mechanisms of ovarian aging, we could potentially develop a therapy that enables you to still have healthy eggs into your 50s, possibly your 60s. But just because we can do something doesn’t always mean we should do it. We know that as women get older, pregnancies are more complicated. You have higher risk for things like high blood pressure, diabetes, and preterm labor. There are many downstream implications, both for the mother’s health and the child’s.

I don’t think the goal should be to enable women to get pregnant into their 60s. Rather, we want women to have the best reproductive lifespan possible – to be able to have children when they want to and to not have children when they don't want to – and to have a society that supports women across that spectrum.

You’ve said that a woman’s ovary may be a “canary in the coal mine” for how the rest of her body will age. What do you mean?

We’re starting to believe that some of the same cellular mechanisms that underlie general aging might also control ovarian aging. This revelation makes the ovary even more interesting to study because its early demise could be a unique window into the body’s aging process. If we can identify cases of accelerated ovarian aging and understand the underlying causes, we might be able to improve not only reproductive function in individual women but also overall health and longevity for all women.

By 2050, what will be possible with reproductive technologies?

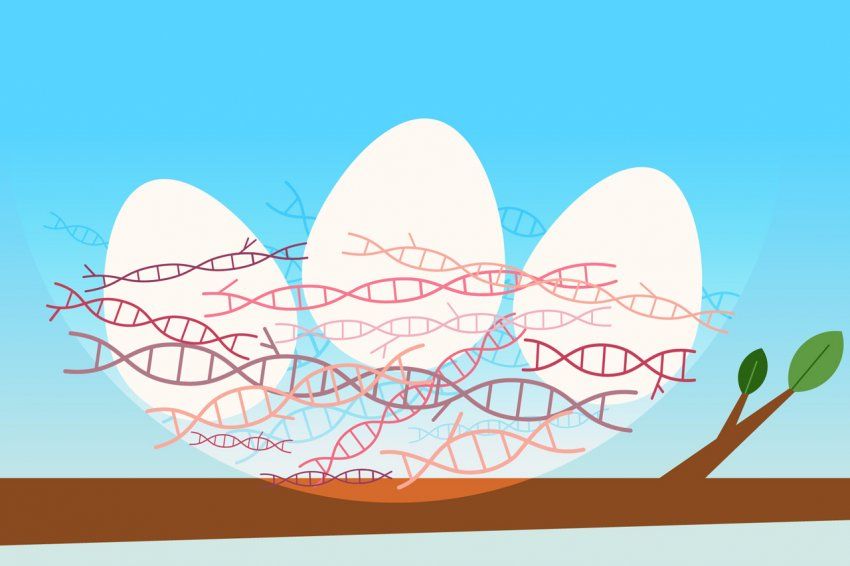

Same‑sex couples having genetically related children is probably on the horizon. Scientists are learning how to take skin cells or blood cells and turn them into stem cells, which can then be turned into eggs or sperm. That’s not science fiction; it’s already happening. We just need to figure out how to do it well and safely in humans.

We’ll probably also see germline engineering. That’s the process of editing genes in reproductive cells or embryos. It has the potential to cure disease before birth. This technology is here. But will society be ready to accept it? A lot of questions need to be answered before it’s put to use. In addition to technical hurdles, there are innumerable social issues. For instance, if we can eliminate a certain disease, will there be less focus on treatments for people who still have the disease? And what about access to care and social equity? Who would be able to afford these procedures? How will they be applied?

What’s the biggest challenge your field faces?

Restrictions are currently preventing the U.S. government from funding research that involves the manipulation of human embryos. As a result, funding for reproductive science is low, which has driven a lot of experts out of academia. If we want to see a revolution in reproductive health, like what’s happening with precision cancer medicine, we need to invest in the development of scientific knowledge that will move this field forward.

UCSF Magazine

Dive into the future of health in this special issue of UCSF Magazine.