His dog – his best friend, his only friend – had died. Distraught, his reasoning clouded by mental illness, “Peter” refused to part with his pet. Instead, he kept its body in the cramped unit of his single-occupancy hotel, where an outbreak of COVID-19 was running rampant. The situation might have spiraled out of control and led to his eviction if not for a simple intervention: a cell phone.

The phone was one of hundreds of flip phones and smartphones distributed in April by Citywide Case Management – a team of UCSF psychiatrists, social workers, nurses, and other staffers – to its clients. Citywide cares for some 1,200 people with severe mental illness in San Francisco who struggle to survive even in the best of times. Their disease wreaks havoc not only on their brains but also on their ability to function in society, often leaving them poor, alone, and living in shelters or on sidewalks.

Prior to the pandemic, the Citywide clinic was a place clients could go not only for treatment but also to connect with others. Photo: Noah Berger

After receiving a call from the hotel, the Citywide team rushed a flip phone over to the manager to give to Peter. “We’re used to going to a client’s room, squatting on the floor, and talking to them for an hour and a half if we need to,” says Alison Murphy, a social worker who leads Citywide’s supportive housing teams. “But I couldn’t have his social worker go into a hotel with COVID.”

Instead the social worker used the phone to help her client process his grief – and ultimately, let his dog go. “The phones have been huge,” says Murphy. “They’ve given us flexibility in how we can care for people.”

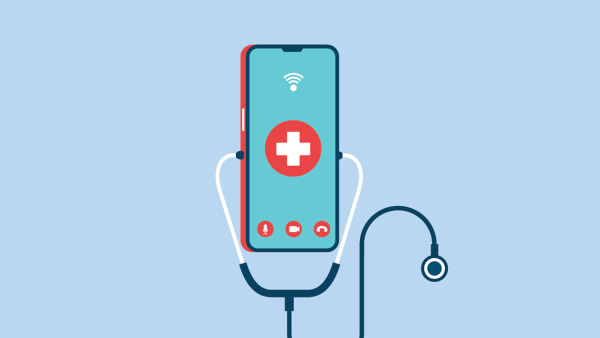

It’s a flexibility few who work with this population saw coming. “Until the pandemic, we rarely thought of telehealth as a possibility,” says Fumi Mitsuishi, MD ’07, MS, director of Citywide, which is a division of the UCSF Department of Psychiatry at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. “The phones have served not only as a lifeline for many clients but also as a jumping-off point for us to close the digital divide that impedes their recovery.”

Hurdles to health

The road to health and stability for Citywide’s clients is strewn with obstacles. Their diseases – schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, acute depression, and others – can often make everyday life overwhelming. For example, paying rent. “There are so many barriers: figuring out how to prioritize it, making a withdrawal, buying a money order, getting it in on time. For people who might not have great organizational skills because of their psychiatric symptoms, it can be really challenging,” says Murphy.

What’s more, their illnesses can make it tough to hold onto jobs, maintain family relationships, or have friends. Some patients grapple with addiction to methamphetamine, opioids, or alcohol. Some cycle in and out of psychiatric hospitals or jails. Many are painfully isolated.

Citywide’s director, Fumi Mitsuishi (right), completed a fellowship in public psychiatry at UCSF. Photo: Noah Berger

Adding to the toxic mix of troubles, Citywide’s clients are often diagnosed with other conditions such hypertension, diabetes, or obesity, says Carrie Cunningham, MD ’10, MPH, Citywide’s medical director. Communicable diseases like COVID-19 also pose a significant threat. The life expectancy for people with serious mental illness is 10 to 25 years lower than the rest of the population.

Despite all these difficulties, their clients might not even understand that they are sick; one of the main symptoms of severe mental illness is poor insight into the disease. “They may never identify as having mental illness,” explains Alison Livingston, a therapist who leads several teams that care for the most acute among Citywide’s clients. “It’s our job to really build a relationship and support them in feeling that we can help them in some way.”

A world crumbles

The team at Citywide considers serious mental illness a societal problem, and that people who suffer from it need far more than medication to recover and lead productive lives. “We are like their family,” says Mitsuishi.

In normal times, Citywide’s clinic near San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood buzzes with activity. Patients come in to receive medication or counseling. They might attend one of the many group therapy sessions held every week, participate in vocational training, or volunteer to help make the daily free lunch. They may stop by just to hang out. “It’s a safe place where they can get off the street or out of their hotel room, see familiar faces, form a community,” says Denise Corbin, a social worker who directs a team that works with 400 of the highest users of psychiatric services in San Francisco.

Citywide caseworkers also journey into the world their patients inhabit, providing support in shelters, hospital psychiatric units, tent encampments, sobering centers, jail, or wherever else they might find them.

But the Citywide family was torn asunder when San Francisco issued shelter-in-place orders on March 16. The team was forced to move its operations to the clinic’s tiny entryway, where only one patient at a time was permitted. They taped the sidewalk outside, marking boundaries for social distancing. Gone were the group therapy sessions, the shared meals, the camaraderie – and for many clients, their only source of stability.

We were literally creating barriers between us and the client, while the whole point is to break down barriers.”

“We went from constantly trying to engage people to asking them to stand behind the blue tape while we talk,” says Murphy. “We were literally creating barriers between us and the client, while the whole point is to break down barriers.” Murphy also had to instruct clients who live in residential hotels to isolate in their rooms. “As a mental health provider who organizes programs, I never thought I’d say that. It’s so antithetical to community-building.”

“We were immediately concerned about what shelter-in-place was going to look like for our clients, especially if they started becoming sick,” adds Livingston. “A lot of adults with mental illness don’t know when to access care, don’t know when to go to the hospital, and don’t have a way to reach out for support because they don’t have a phone.”

Telehealth trials and triumphs

When the sheltering orders came down, “it became very clear that we needed to shift to remote work and telehealth,” says Mitsuishi, the director. “We were fortunate to get an infusion of donor-gifted phones.”

A slew of questions ensued, many of which had held the team back from pursuing telehealth in the past: Will clients be able to use the phones? Will they answer them? Will they lose them? Can they keep them charged? Will the phones get stolen? Who already has a phone? And what kind of telehealth do we want to provide? Therapy sessions? Check-ins? Zoom groups?

With little time to ponder, the team had to just plunge in. They did their best to determine which clients most needed a phone and what type – flip phone or smartphone – each client could manage. Then they set about getting the phones into their clients’ hands. As for the rest of how telehealth would work? They had to figure it out, for the most part, on the fly.

“We just started a system of literally going down our roster of clients every morning,” says Murphy. “Calling them and saying, ‘Hey, how are you doing? How are you feeling? Are you having any symptoms? What’s up with food? What are you doing to take care of yourself’”?

Not only did clients answer the calls, they did something that surprised Citywide: They called their caseworkers. “We thought of the phones as a way to connect with our clients,” says Cunningham, the medical director. “We didn’t realize this would be an avenue for them to call us more.”

Fumi Mitsuishi speaks with a client in 2019. The Citywide team has had surprising success using cell phones to deliver care during the pandemic. Photo: Noah Berger

The calls have been lifesaving in many instances, says Mitsuishi. In one situation, a client had been exposed to COVID-19 while in a psychiatric emergency services unit but wasn’t informed of the exposure. A contact tracing team reached his social worker, who was able to alert him and immediately help him self-quarantine. In another case, a social worker was able to reach a client who had overdosed on fentanyl and persuade him to enroll in a recovery program. Countless other calls have allowed social workers to provide emotional support and help clients get food, Social Security benefits, and other essential resources.

And in their clients’ isolated and fraught circumstances, the calls have served as a conduit to a human connection. “We’ve had people break down in tears knowing that they could call their family,” says Murphy.

This type of connection has been especially crucial. Schizophrenia, for example, “tends to break people out of all their social networks. That’s exacerbated by the pandemic,” says Corbin.

The evidence showing that telehealth has been successful is more than anecdotal. Mitsuishi conducted a survey of clinicians, which showed the effort increased cell phone access to their clients by nearly 40%, that most clients are keeping their devices, that most have internet access most or all of the time, and that only a quarter of clients required technical assistance. The team has also made use of iPads and Zoom, though they are still figuring out the best way to implement those tools.

Of course, telehealth has not proven suitable for every client and every situation. Video calls, for example, may not work for people experiencing psychosis, explains Corbin. A few clients have lost their phones. Some can’t grasp the technology. Others have complained they’d rather see their social workers in person.

We have to be [out-of-the-box thinkers] because our clients don’t fit into nice, orderly ways of interacting with the world. We have to find a way to make the world fit for our clients.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by the Citywide team. “It’s been hard because our work has always been so face-to-face, like, ‘Let’s meet, let’s talk, let’s be near each other. Come in, open arms, we’ll take care of you.’ We’re literally so physically present for our folks,” says Kathleen Lacey, a social worker who directs a program that works with clients involved with the justice system.

Yet the pandemic has pushed the team to do what it does best. “We’re out-of-the-box thinkers,” says Lacey. “We have to be that way because our clients don’t fit into nice, orderly ways of interacting with the world. We have to find a way to make the world fit for our clients.”