Tackling Childbirth-Related Mortality in the World’s Poorest Place

New School of Nursing program aims to turn the tide on preterm births in Malawi.

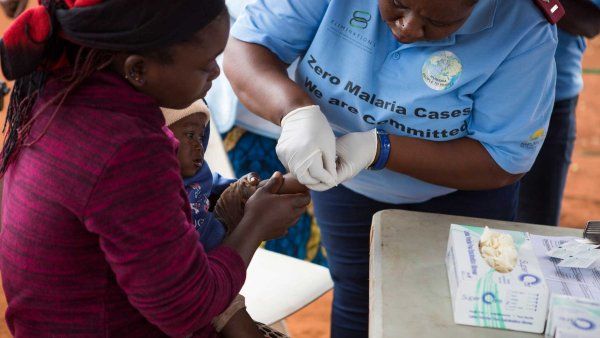

A new UCSF School of Nursing program in Malawi will launch this fall in the hope of turning the tide on childbirth-related mortality and addressing the nation’s critical need for nurse and midwife training.

In Malawi, a small, landlocked nation in southeastern Africa, hardly anyone congratulates a woman who is pregnant. They will do so only after she gives birth, and then only if both mother and child survive.

That’s because Malawi, the poorest country on the planet, has the world’s highest rate of preterm births. Women there have a one-in-29 lifetime risk of dying from childbirth-related causes. And their babies face even more dire odds: The neonatal mortality rate in Malawi is 22 per 1,000 live births, or one in 45.

Such statistics are almost unimaginable to those living in the U.S., where the maternal mortality rate is just one in 3,800 and the neonatal mortality rate is just four per 1,000 live births (or one in 250). But that discrepancy is all too real to Melanie Perera, MS ’12, who spent three years training nurses in Malawi.

“In one year there,” says Perera, “I saw more babies and children die than I’d seen in five years as a nurse at Stanford.”

Perera didn’t hesitate when she was asked by School of Nursing faculty members Kimberly Baltzell, RN, PhD ’05, and Sally Rankin, RN, PhD ’88, to direct a new program called Global Action to Improve Nursing and Midwifery (GAIN). Baltzell and Rankin, founding directors of the nursing school’s Center for Global Health, created the program to train Malawian nurses in leadership and clinical skills and to offer on-site coaching for a year afterward. They hope the program will not only turn the tide on childbirth-related mortality in Malawi, but also help address the nation’s critical need for nurse training.

GAIN will launch in September with a cohort of 20 Malawian nurses. The trainees will learn clinical practices based on World Health Organization standards, which range from identifying dangerous postpartum bleeding in mothers to implementing lifesaving skin-to-skin contact between mothers and preterm or low birth weight newborns. In creating the curriculum, program leaders are working closely with Malawian colleagues and international organizations such as Partners in Health.

The leadership training and ongoing mentoring are crucial. After the classroom training is completed, a nurse expert in midwifery or labor and delivery will coach the learners where they work, helping them improve clinical quality.

Train-the-trainer programs such as GAIN have shown dramatic results in other locales. After only one year of a pilot program at Gobabis District Hospital in Namibia, for example, maternal mortality dropped from 153 of every 100,000 live births to zero, while stillbirths were reduced by nearly half and early neonatal mortality by one third. Such training has also been shown to give a significant boost to the participating nurses’ self-confidence.

Saving a mother’s life saves the entire community from a whole constellation of effects.”

Reflecting on her time in Malawi, Perera says, “I saw nurses grow in self-respect, in the knowledge that they each have a unique gift to bring to their practice. As they grow more confident, they become advocates for their patients.”

Baltzell points to the even wider ripple effect of such improvements.

“When you lose a mother in childbirth, you lose a stabilizing force in the community,” she says. “Orphaned children have long-term educational and economic deficits. The consequences are profound. Saving a mother’s life saves the entire community from a whole constellation of effects.”