The name OME is not an acronym but comes from the suffix -ome, which in biology is used to denote a totality of precise elements and their interrelationships. Thus the entirety of a person’s genes forms a genome, proteins form the proteome, microbes form the microbiome.

A call goes around your office for donations. But the volunteers leading this drive aren’t seeking toys, books, or even canned goods – they want your genetic data.

You just might receive such a request soon if the ideas generated at the first global OME Precision Medicine Summit, convened by UC San Francisco, morph into reality. The concepts and plans that emerged from the summit this past spring – as unusual as some might sound today – could help make medicine more predictive, preventive, and precise.

UCSF is pursuing this ambitious goal – which entails harnessing technological prowess, scientific acumen, and medical records – to better understand the roots of disease and develop targeted therapies. But the road to precision medicine is filled with challenges: How do we collect and analyze the vast amounts of genetic and biological data stored in different places and formats throughout the world? How do we encourage people to share their personal health details? How do we address regulatory barriers? How do we pay for it all?

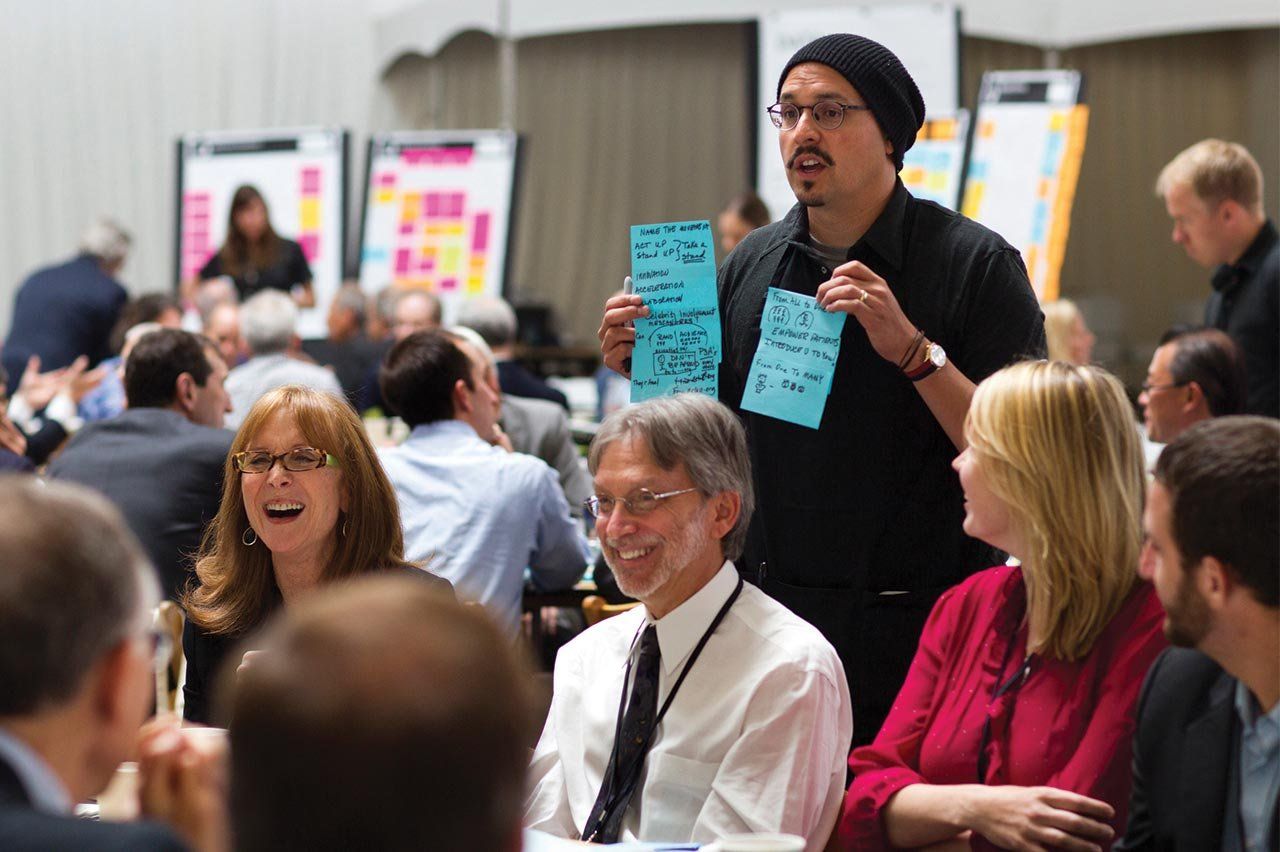

Even individually, much less cumulatively, this is no small charge – which is why 170 top scientists, entrepreneurs, technology gurus, business executives, and government leaders found themselves at UCSF Mission Bay for two days in May.

Developed with the global design and innovation firm IDEO and staged inside the gym at the William J. Rutter Center, the summit was far from a talking-heads conference.

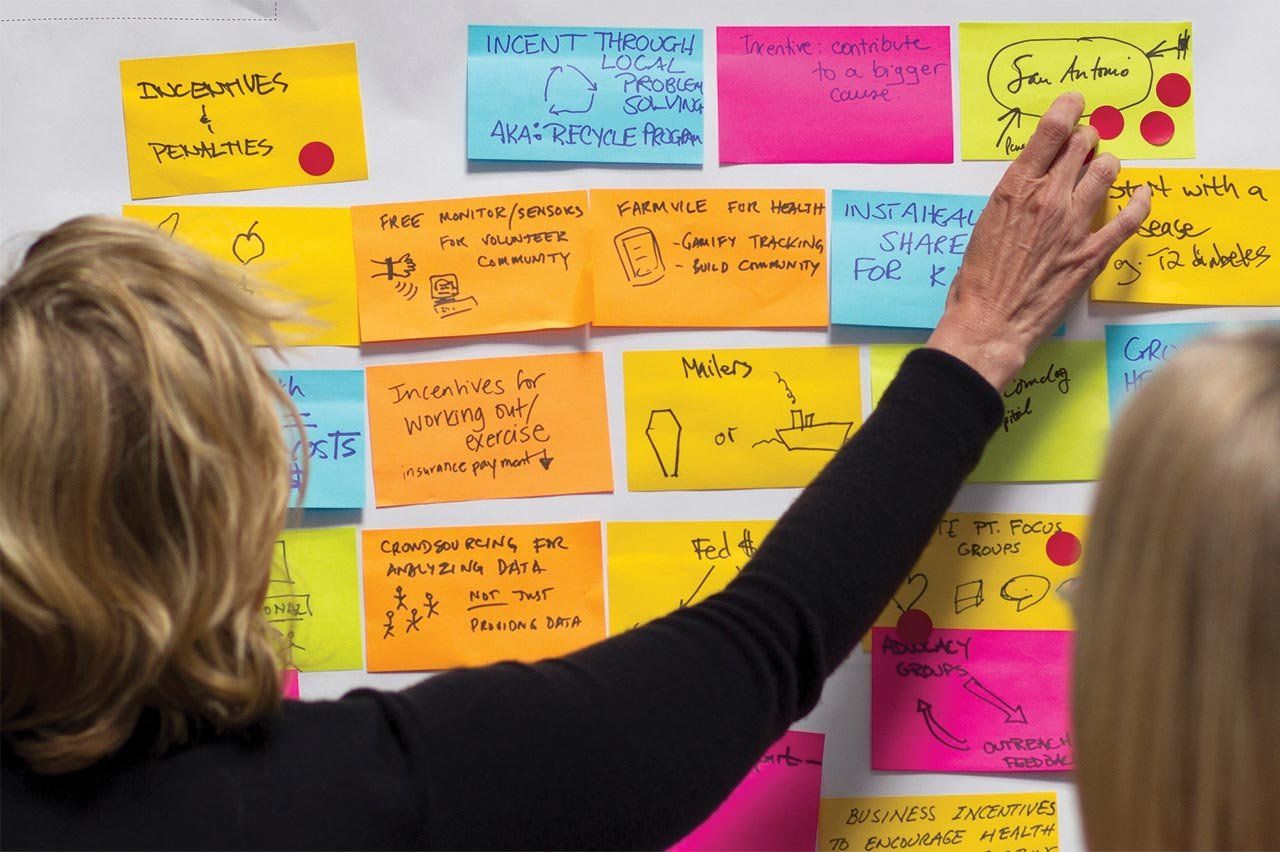

Surrounding a raised platform that served as a stage stood whiteboards covered with zigzagging charts and doodles. Comfy couches, and tables stacked with fluorescent Post-it notes, encircled the room. Coffee flowed freely.

In the midst of it all, luminous minds were hard at work.

Ideas posted on sticky notes. Photo: Deanne Fitzmaurice

Guide for the two action-packed days. Photo: Deanne Fitzmaurice

Ann Wojcicki, CEO and co-founder of 23andMe, concentrating on a teammate’s explanation. Photo: Deanne Fitzmaurice

A facilitator from IDEO leading a brainstorming roundtable. Photo: Deanne Fitzmaurice

UCSF Foundation board members Leigh Matthes and Lynne Benioff (both seated) sharing a laugh with UCSF Chancellor Susan Desmond-Hellmann and (on the far right) Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Jeffrey Bluestone. Photo: Deanne Fitzmaurice

NIH Director Francis Collins listening to Lloyd Minor, dean of Stanford University School of Medicine. Photo: Deanne Fitzmaurice

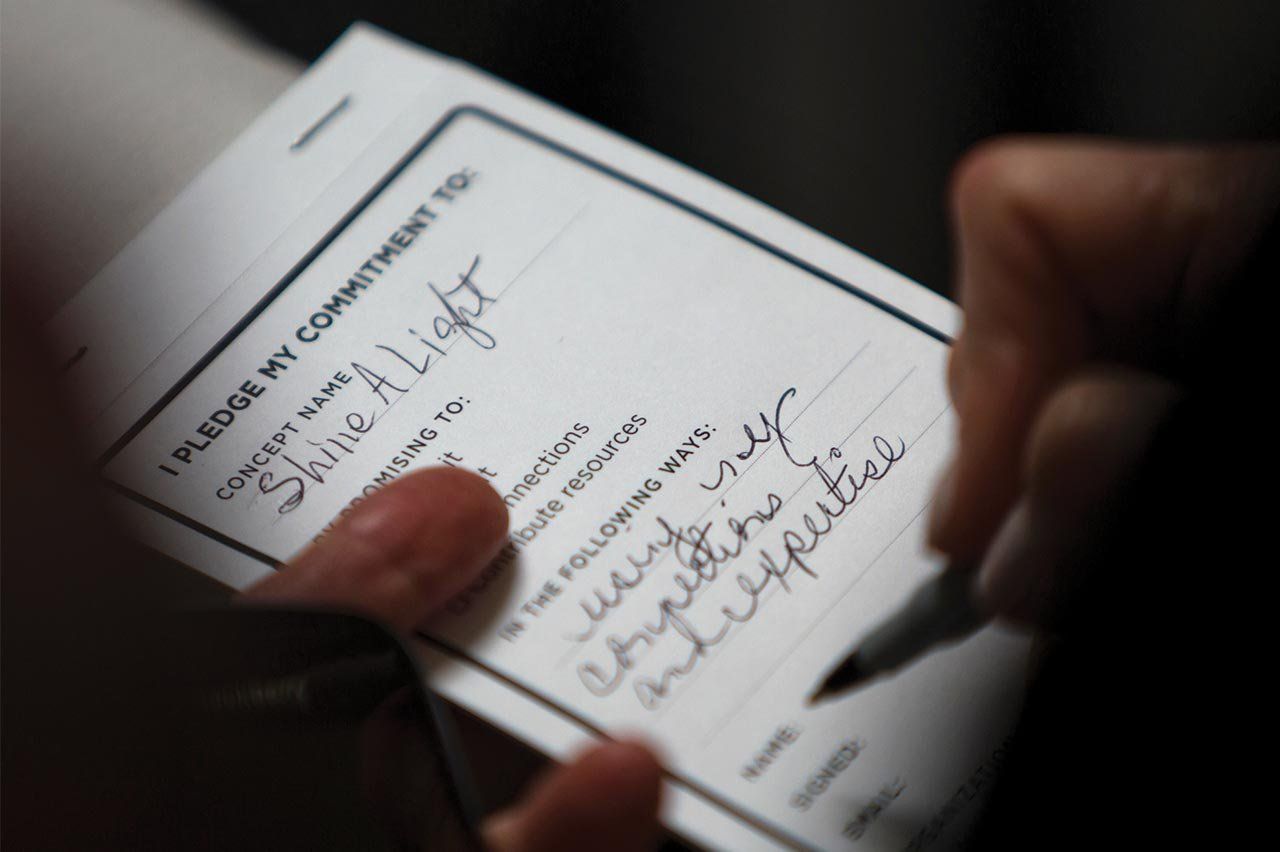

Participant commitment pledge sheet. Photo: Deanne Fitzmaurice

Steven Burd, former CEO of Safeway. Photo: Deanne Fitzmaurice

UCSF Vice Chancellor for Research Keith Yamamoto (right), and Rémi Brouard, a vice president of the global pharmaceutical company Sanofi-aventis, delivering their pitch. Photo: Deanne Fitzmaurice

“Today people are diagnosed with diseases – diabetes, breast cancer, lung cancer – and precision medicine is about connecting the dots in a new, data-driven way so we can understand the underlying biology,” OME leader and UCSF Chancellor Susan Desmond-Hellmann, MD, MPH, told the participants in her opening remarks. “It could completely transform the way pharmaceutical companies and biotech approach development. It could turn a multi-decade process into a rapid process.”

Fired by that vision, participants were split into teams to encourage a flow of ideas across industries and disciplines. Each team was charged with tackling one thorny obstacle to implementing precision medicine.

Huddled in one corner might have been the president of the Institute of Medicine, a leading cancer researcher at Pfizer, a prominent Silicon Valley venture capitalist, and a cutting-edge scientific illustrator. Hashing out details at a whiteboard, one might have seen the director of Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, the dean of Hong Kong’s top medical school, and a space technology expert. And conversing here and there, one might have spied the FDA commissioner, a partner at TEDMED, a seasoned political strategist, and the head of Rockefeller University.

At one point, even Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg stopped in to listen to the deliberations, as did California Governor Jerry Brown.

“It’s pretty amazing to be in the room with so many leaders in the whole area of precision medicine from inside and outside the country,” said Francis Collins, MD, PhD, director of the National Institutes of Health and an OME participant. “We’re working on projects that could be initiated, that could bring us closer to dramatic developments for prevention and treatment of disease.”

Watch innovators at OME speak about precision medicine.

The summit culminated in a quick-pitch session, during which teams presented pilot projects designed to surmount barriers and make precision medicine a reality.

Desmond-Hellmann gave the final presentation, stressing that the keys to making precision medicine work are raising public awareness, getting support for new legislation to change patient privacy laws, and enlisting people to donate their data in the interest of helping their loved ones – and humanity.

“We will leave this summit not only with an action plan,” she said, “but with 170 incredible human beings who will take the messages we’ve shared and honed back to their day jobs – and that has enormous value.”

Select OME Pitches

By Louise Chu and Juliana Bunim

Smart Toilet

Create a “smart toilet” that could analyze stool samples, which are a key health indicator. The toilet would use the data in a real-time health dashboard that could be accessed by the patient’s family members and doctors, and it could also send anonymous data to researchers interested in looking at patterns on a larger scale.

Lessons learned from Failed Clinical Trials

Make public data from the vast majority of failed clinical trials for drug treatments. That data is valuable to other researchers tackling the same problems, yet the Food and Drug Administration isn’t allowed by law to release it, and pharmaceutical companies don’t have any incentive to share it. Making the data public would require a change in legislation, or an agreement among major biopharma companies and research universities like UCSF.

Global Biological Data Consortium

Form a global consortium that would establish standards for collecting and analyzing biological data. Currently, research data doesn’t have any such standards, a situation the team likened to “Betamax versus VHS.” The consortium would ensure that researchers begin working in the same data language, starting with a couple of pilot disease areas.

Precision Medicine Technology Foundation

Create a nonprofit foundation that would certify precision medicine technology for early reimbursements. Typically, there’s a six-year cycle to bring ideas to market, but often money begins to run out after the first couple of years. The foundation, which could be funded by major health care providers, would help promising projects get on an accelerated track and reduce risk for innovators.

Immersive Data Visualization Database

Develop a computational database with a unique user interface able to manipulate complex data sets. The system would be a way to visualize data that could accelerate the pace of scientific discovery for neurodegenerative diseases. UCSF neuroscientist William Seeley, MD ’99, has partnered with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Oblong Industries to create a pilot project using 10 years’ worth of research data collected by Seeley, but financial resources are needed to expand the project.

Data Donor Drive

Approach gathering genetic data the same as running a blood drive, by tapping into people’s sense of volunteerism and philanthropy. Start a grassroots campaign that seeks to collect one million data sets.