Adapted from a video interview.

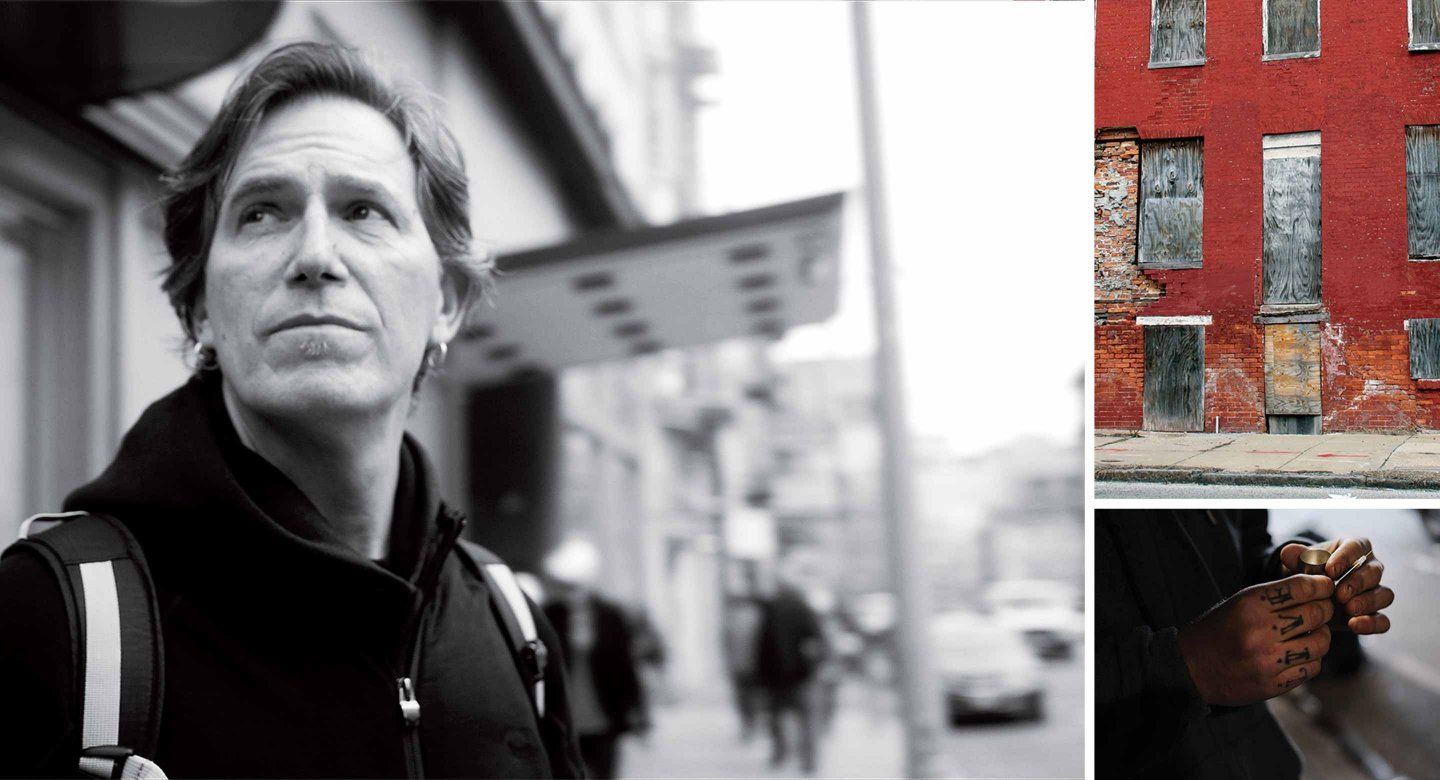

I’ve been studying the problem of street-based drug use for 18 years. I’m currently the principal investigator of Heroin in Transition (HIT), a five-year study funded by the National Institutes of Health.

HIT’s objective is to better understand the heroin crisis. The study involves multiple disciplines, some of which are quantitative, like economics and statistical modeling. But it also has a qualitative component, which draws on medical anthropology and ethnography. We spend time with folks who use heroin and talk with them about their drug use. We want to understand, really understand, the lived experience of those who are experts in heroin: the users themselves.

We do this work in alleyways, in boarded-up buildings, in dank places that often smell of urine, because that’s where the action is. We want to watch it happen in its natural setting, to learn from the real world.

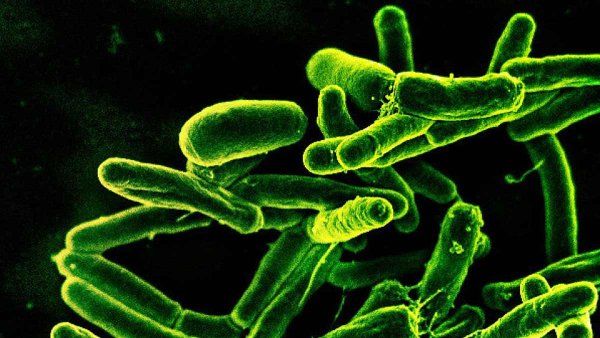

Our nation’s heroin and opioid crisis has become more and more horrific. Drug overdose deaths now exceed those caused by car accidents and gun violence. It’s a complicated problem, because heroin comes into the United States from many sources. Each source has a different chemistry, is used in different ways, and leads to different public health consequences, from HIV to endocarditis [an infection of the heart valves or inner lining of the heart]. And most devastatingly, many sources are now contaminated with fentanyl and other cheap synthetic heroin analogs. These synthetics are causing wave on wave of medical consequences – including overdose deaths, since they’re many times stronger than street heroin.

Our street-based research is both the most poignant and most rewarding part of our work. My team and I go all around the country – to big cities and small towns alike – and identify and talk with folks affected by heroin and the new synthetics. We’re looking for indigenous insights into this crisis.

The data portion of our work is important, but this qualitative work offers insights we simply can’t get from statistics. In 2016, 64,000 people died of drug overdoses. But if we focus just on the numbers, their voices are lost. Who were those 64,000 people as individuals? What led them to use? Why did they die?

Photos: Daniel Ciccarone

States with highest rates of death from drug overdoses in 2016:

-

West Virginia

-

Ohio

-

New Hampshire

-

Pennsylvania

-

Kentucky

64,000: Deaths from drug overdoses – of which opioids are the main driver – in 2016.

Statisticians don’t get to “why” questions, but ethnographers do. So our ethnographic work helps us understand what leads individuals to do things that put them at risk. Then we can circle back and put those risk factors in a statistical model.

We’ve engaged with a wide range of people affected by this epidemic: Folks who’ve been using heroin for three months and folks who’ve been using for 60-plus years. Young people and old people. People living on the streets and people with jobs. White and black. Rural and urban. We’ve talked with moms and dads who’ve lost children to overdoses. We talked with a man in West Virginia who’s lost half of his high school class to pills and heroin.

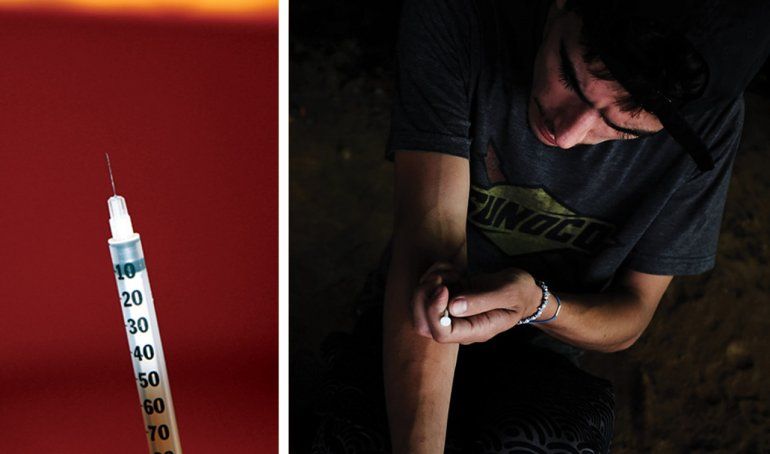

This qualitative work, while it’s really rewarding, is also challenging. Because drug use is illegal and highly stigmatized, drug users are difficult to find. We recruit them at needle exchange programs, at clinics, at public health agencies. We try to gain their trust; they usually agree to talk with us and introduce us to their social circle. Then we go sit with them wherever they hang out – in alleyways, in their homes, in their cars – and we talk.

I’ll often start by asking what drugs they use – a typical doctor question. Then I’ll get into more disarming questions – say, “Tell me what you like about the drug you use.” That’s a question someone

in law enforcement wouldn’t typically ask; it shows I’m genuinely interested in the person. Then I might ask, “What brought you to this neighborhood?” or “Tell me how you go through your day.”

We always ask open-ended questions, not leading questions. This is just like in a clinical encounter, when we are trying to build rapport and get the patient’s perspective. And we’ll say “I want to hear about your experience – you’re the expert, not me.”

Photos, left to right: Daniel Ciccarone; Spencer Platt

Ciccarone calls the current crisis a “triple wave epidemic.”

First Wave was the prescription painkiller epidemic, in which powerful opioids were prescribed at alarming rates, causing mass dependency issues that continue today.

Second Wave made landfall in 2010, as former prescription drug patients and other new users came into heroin use, leading to a tripling of heroin-related overdoses since then.

Third Wave has arrived in the form of new, and alarmingly powerful, synthetic opioids.

We ask some fairly intimate questions. But once we’ve built rapport, we’re in. They let us in because we show we care about them and their concerns. I try to approach everyone as nonjudgmentally as I can – as a witness, not an examiner.

And when people hear our questions – and our responses to them, such as “I’m sorry to hear that” or “I’d like to hear more about that” – they can tell we come from a neutral place. These folks don’t feel heard by society. They often don’t feel heard at the doctor’s, for example. They certainly don’t feel heard by the legal system. We’re trying to give them a voice. When they perceive that from our questions, from our whole process, they open up and tell us stuff – stuff we plan to turn into papers, into tweets, into newsfeeds, into political action and policy changes that will turn around this crisis.

Sometimes I’m asked if I ever feel afraid. We do go places that can be pretty disturbing – abandoned buildings, hovels, secluded alleyways – places not fit for human habitation. We see peeling wallpaper, mattresses on the floor, detritus everywhere. We see and smell evidence of incredibly poor hygiene, evidence of sexual activity. I’ve even seen knives and guns. It can feel edgy. But we always go in teams of two or three; if any member of a team doesn’t feel safe, we don’t go. And we never go anyplace we haven’t been invited.

There’s something about being with people in their everyday environment that helps them open up. Say you’re in the habit of going to a café and sitting down over a cup of coffee or tea – that would feel to you like a natural place for a conversation. So being with these people in the places where they hang out with their friends, where they buy or use drugs, feels natural to them.

Photo: Daniel Ciccarone

Heroin

An opioid drug made from morphine, a natural substance taken from the seed pod of the various opium poppy plants grown in Southeast and Southwest Asia, Mexico, and Colombia.

Opioids

A class of drugs that includes the illegal drug heroin as well as pain relievers available legally by prescription.

Fentanyl

A synthetic (human made) opioid analgesic that is 30-50 times more potent than heroin and 50-100 times more potent than morphine.

We’re trying to document reality for these folks. Typically we have recorders running, though sometimes we take furious notes after we leave. We record them making the solution, bringing it up into the syringe, and then injecting it. We document the entire process so we can look for micro-practices that might be risky or that might be protective.

We’re now three years into HIT, and we’ve learned a lot – some of it commonsensical, some of it shocking. The level of despair in certain parts of the country is unfathomable.

But at the same time, we’ve learned that there’s tremendous resilience out there. People are learning to deal with this poison called fentanyl. Remember, fentanyl is typically not something drug-users choose – it’s a contaminant of heroin. With any given drug purchase, people don’t know what they’re getting. It’s sadly like “Russian roulette.” So people have developed ways to test their drugs, to change their behaviors, to try to stay safe. These things are happening organically, not through public health interventions. But could we turn them into public health interventions? I certainly hope so.

That’s why it’s important to remain curious, both about what we observe and about what those observations may hold in terms of outside-the-box solutions.

People also ask me what it’s like to do this work. I grew up in the streets of New York, so I’m a pretty tough cookie. But it’s important to find a balance between being tough enough to go into these places and see what we see, yet do it with a kind of softness and humility that allows us to be receptive to really hearing people’s stories.

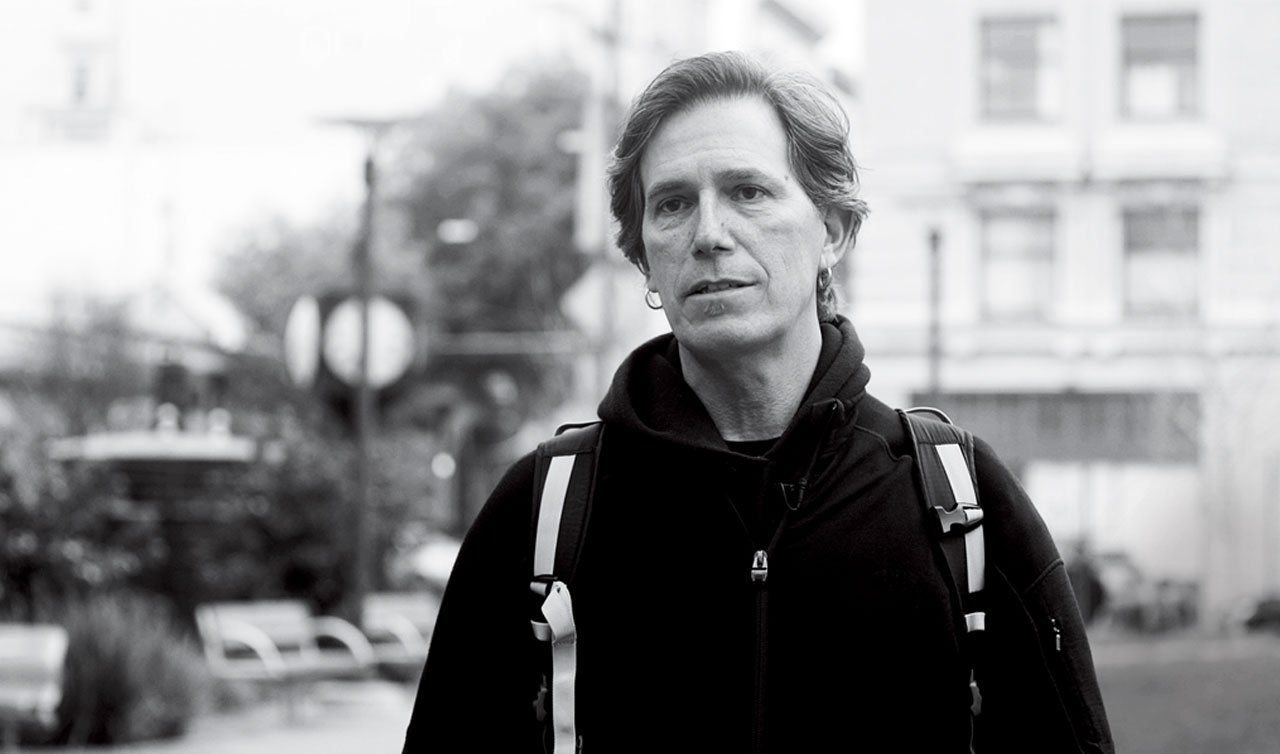

Photo: Lawrence Rickford

When I’m in the street, I become a different person. I actually feel different when I’m out there. When I walk into clinic wearing a white coat, I feel a sense of professionalism, a certain sense of hubris as a doctor. But when I go out in the field, I do the opposite. I try to go in as humble and simple as possible. I might wear black if I feel that would fit with the scene. I sit lower than everyone else; I’ll often sit on the floor, even if it’s filthy. I’ll try to make eye contact if it seems welcomed, or I’ll avoid eye contact if that seems best. I might even ask questions from across the room, if that’s what it takes to make the person feel comfortable.

I truly don’t have much fear or concern working with this population. I love what I do. I believe I’m the right person for the job. In fact, doing this research allows me to fulfill multiple parts of myself. I get to be an engaged clinician, and I get to stay curious. I can imagine paths I could have taken where my native curiosity would have been squelched, but this research, diving into this hard problem, keeps me alive. It’s a pessimistic problem, but I’m an optimist. And I’m optimistic that we’ll find solutions, especially to the stigma and the prejudice.

Stigma is a huge barrier in our society. I think a generation or two from now, we’ll be embarrassed by how we currently regard drug use. We’re now getting insights from neuroscience, for example, about how addiction is a brain disease, how it rewires people’s neural pathways. We want to end the stigma for this highly misunderstood population and problem. I predict that we’ll be out of the blame game in a generation or two – which will lead to better policies.

Unfortunately, this epidemic isn’t going away any time soon. That’s one of the saddest insights I have. For example, you might wonder why a deadly chemical like fentanyl is used by drug lords – wouldn’t simple economics lead them to say, “Whoa, we’re losing our customer base.” But it appears more users are coming in than are passing away; I don’t have proof of that yet, but I think it’s the case. That’s the most horrible thing we’ve discovered.

We need to stem this crisis, and then we need to reverse it. That’s why we are identifying the strategies that people are using to stay safe.

Daniel Ciccarone is a professor of family and community medicine and resident alumnus.

Photos of people using drugs in this story are editorial photos (not research participants).