How Can We Help Kids Cope with Anxiety about Climate Change?

The existential dread children feel about the climate crisis is a new phenomenon that requires our attention.

We spoke with Ellen Herbst, MD, a UCSF psychiatrist and mother of two, about how the climate crisis is impacting the mental health of children and adolescents – and what parents can do to help.

Professor of Psychiatry

When did you start thinking about this?

It started with my older son, who is now 13. When he was in fourth grade, he learned in science class about the reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. He came home devastated. He was crying and feeling hopeless. He was saying, “What’s the point?” and “No one cares.”

I realized that this crisis is a huge burden for young people. Children are, appropriately, being educated about climate change in many schools and learning about it in the news, but they’re not necessarily given the coping skills to handle that devastating information.

What did you do?

As an adult psychiatrist with expertise in traumatic stress, I know that the climate crisis impacts my patients. But with my own two kids, I just felt stuck. I wasn’t sure how to tell my child that he was right: Things aren’t certain, and they may not resolve how we want them to. I decided to educate myself about how, as a parent, I can support my kids.

What did you learn?

I learned that this is not an isolated experience. My son was communicating what many kids are feeling: betrayal, uncertainty, and disempowerment. Some are terrified.

A study recently came out that surveyed 10,000 young people in 10 countries. Across this diverse sample, the majority of respondents were worried about climate change, reporting feelings like sadness, anxiety, anger, and helplessness. These are grief-related emotions. What struck me is that climate grief and distress are becoming universal, particularly for youths.

We know that low-income communities and communities of color in developing countries are disproportionately affected by the climate crisis. People in these areas are experiencing acute trauma related to losing their homes, a sense of safety, even loved ones. Then there are kids who are experiencing chronic impacts during and after climate disasters, like poor air quality or insufficient schools or buildings that are damaged beyond repair. Communities closest to the crisis deserve resources, time, and serious attention.

Kids like my son are coping with an existential dread. He hasn’t lost his home; he hasn’t lost loved ones. But he feels like the clock is ticking. We know a great deal about how to cope with the effects of acute disaster and trauma, but the existential grief related to climate change is a new phenomenon that also requires our attention.

How do we help our kids cope?

An emerging area of inquiry, including here at UCSF, is around building psychological resilience to climate change. That means being able to cope internally, so when a child is faced with disturbing information or worrisome realities, they have a way of grounding themselves, of continuing to function, of not going straight to despair. They can live with this heavy knowledge and still reach their potential and thrive.

There are many ways of promoting resilience in kids. It might involve spending time in nature with other kids who care as deeply as your child does. For some children, climate activism can be gratifying. It could involve writing a letter to a policymaker, starting a school club, or restoring a wildlife habitat. Social activities set in nature can help a child feel more connected and like they’re making a positive impact. Age-appropriate mindfulness practices can also help.

My kids and I participated in an activity with Nature in the City. We restored a butterfly habitat in San Francisco’s Sunset District. Both kids really loved it because it involved a direct connection with nature. It felt like we made a concrete, positive impact.

We also try to talk about what we can do during our regular conversations as a family, as opposed to ruminating on the worst-case scenarios. That has made a difference. And we talk about the disproportionate impact that this crisis has on the most vulnerable communities.

What’s your advice for parents?

Kids, especially younger children, often think in black and white. If they read a news article or climate report, they may think the world is ending. I try to explain that it’s not all or nothing. If some species and ecosystems are saved, that matters.

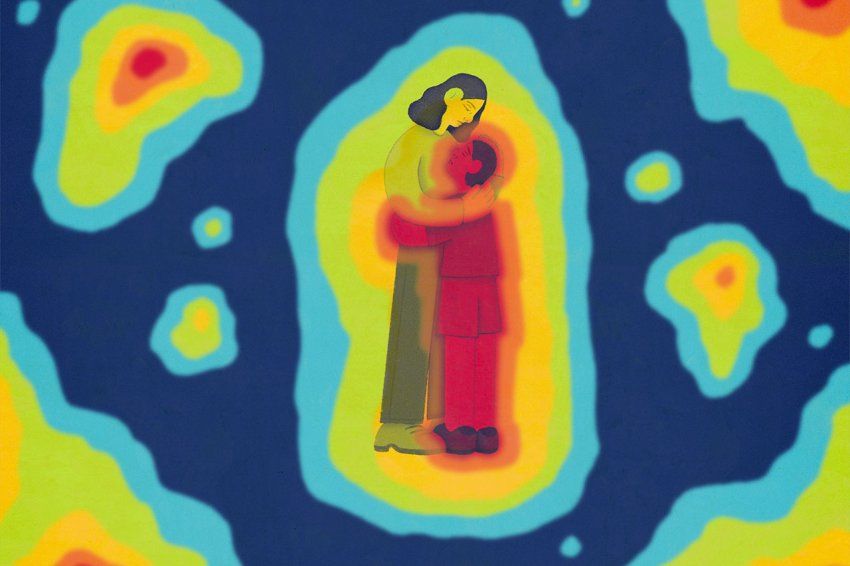

It is also so important to remember that the primary need of a child is to feel safe. If we cannot provide that within the external world, we must try to promote safety between the parent and the child. So be honest with them. Tell them that you’re not sure what’s going to happen but remind them that you care and will be there with them, no matter what.

Ellen Herbst, a UCSF resident alum, is a clinical professor of psychiatry at the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences; a member of the UCSF Mental Health and Climate Change Task Force and the Climate Psychiatry Alliance; and a staff psychiatrist for the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System. The views expressed here do not reflect those of the U.S. government or the Department of Veterans Affairs.