Heads Up: A Primer on Concussions

An expert on this common brain injury answers some frequently asked questions.

Photo: Yobro10

Carlin Senter, MD, an assistant clinical professor of sports medicine, was recruited to UCSF four years ago to lead the concussion program. One year ago, she helped launch the Bay Area Concussion and Brain Injury Program in collaboration with UCSF Medical Center, UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, and San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center.

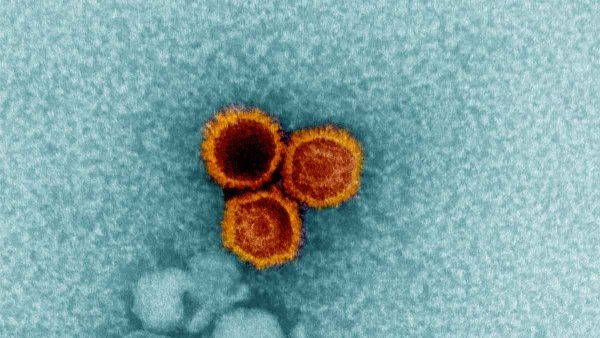

What is a concussion?

An injury to the brain caused by a blow to the head, neck, or body. It’s followed by an onset of symptoms – usually immediately, but sometimes delayed for up to 48 hours – including headache, confusion, difficulty concentrating or remembering, dizziness, problems with balance or coordination, fatigue, nausea, and depression or anxiety. Physicians diagnose concussion based on this classic history; there’s no MRI or blood test that can diagnose concussion.

Who is most likely to experience concussion?

High school athletes – among boys, football players, and girls, soccer players. We also see a fair number of adults who were in bicycle accidents. There are 3.8 million sports- or recreation-related concussions in the US every year.

What’s the best treatment?

Rest – both cognitive and physical. Take time off from work or from school, if necessary. Do not return to play on the same day as the injury and take at least a week or two off from physical activity. We recommend staying away from loud, crowded environments and video games because they’re too stimulating, and we sometimes recommend taking a break from using a computer because that kind of eye movement promotes dizziness. And don’t drink alcohol. The risk of repeat concussion is highest in the first seven to 11 days postconcussion, so it makes sense to wait and let your brain recover.

Are there patients who don’t recover in the typical one to three weeks?

About 10 percent of people recover more gradually or didn’t receive the right treatment off the bat. For patients with postconcussive syndrome, we run a monthly multidisciplinary clinic where we bring together a variety of experts in sports medicine, neurosurgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation, neurology, neuropsychology, physical therapy, and neuroradiology. We see patients as a team and come up with a comprehensive treatment plan.

What about long-term consequences, such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)?

CTE is a progressive degenerative disease that can only be diagnosed on autopsy. It was found in former NFL player Junior Seau, for example. While concussion and CTE are associated, it has not been proven that concussion causes CTE. We need more research in this area. UCSF is part of a multicenter study looking at longitudinal risk in college football players compared to professional players. This fall we’re kicking off a research project examining postconcussive syndrome patients to develop some objective tools for diagnosis. We’re interested in correlating brain changes on MRI with how a patient is functioning.

Wouldn’t it be safer to keep children from playing sports?

There are so many great benefits from playing sports. That’s why I’m a sports medicine doctor. My main goal in being a physician is to help people be physically active, so if they’re experiencing a pattern of head injuries, I help them to choose a sport that’s lower risk. Rather than football, what about basketball? Rather than soccer, what about softball? You can still be an athlete.