“UCSF attracts a special type of student,” says dentistry professor Steve Silverstein, DDS, MPH, a public health veteran. “They’re drawn to San Francisco for its legacy of social justice, and they give back while they’re here because it’s in their DNA.”

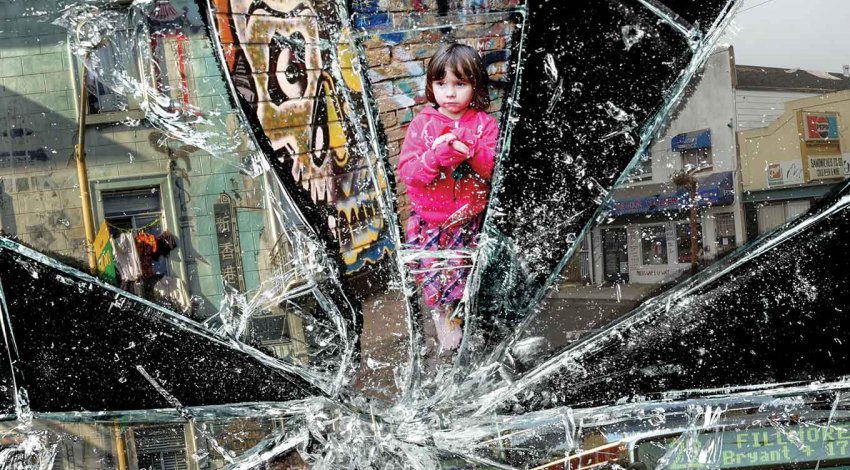

The many ways in which UCSF students reach out to the community are as diverse as the City itself, from combating Hepatitis B to hosting radio shows about science careers. These efforts fill a void for the underserved, and can also spark revelations for students about the social determinants of health – the cultural, economic, genetic, and behavioral factors that threaten the well-being of entire communities.

UCSF has a legacy of community health that starts in its backyard and extends around the globe. At Glide Health Services in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, School of Nursing resident Vivian Sha (center) mentors new resident Lisa Masai (right) as they consult with a patient. Photo: Steve Babuljak

Vivian Sha, NPC, just completed a full year’s immersion in community health at Glide Health Services, located in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco. Managed by nurses, the federally qualified center provides vital primary care to some of the city’s most impoverished patients – and mentors students like Sha, who seek to treat the underserved as part of their training.

Three years ago, Glide expanded its scaffold for these trainees by partnering with the UCSF School of Nursing in a joint nurse practitioner residency, among 10 programs nationwide to receive a three-year Health Resources and Administration grant. Sha was one of the program’s first two graduates.

“Community health is different. The pace is faster, there are a lot of elements, and there’s not much support,” says Pat Dennehy, RN, MS ’99, DNP, UCSF nursing professor and Glide’s director. New graduates often require more mentoring; without it, they tend to leave safety-net practices, she explains. “Our program strives to provide that support.”

Community health is different. The pace is fast, there are a lot of elements, and there’s not much support. Our program strives to provide that support.”

“Most of our patients at Glide don’t just have complicated medical backgrounds,” says Sha. “They often have psychosocial issues like addiction, depression, or exposure to violence. They may be marginally housed, if housed at all.” Many are not – 75 percent of the clinic’s patients have nowhere to call home.

Evidence of how social disparities undermine health is abundant at Glide. Lifesaving screenings or treatments, even when free, remain out of reach for some of Sha’s patients, who may not have the transportation to attend appointments or the skills to read what are typically complex instructions written in English.

So-called “patient noncompliance” can also have more heart-breaking origins. For example, when women patients kept missing their mammogram appointments, the Glide staff investigated and learned why: without access to clean undergarments and a shower, the women were too embarrassed to be examined. Glide now supplies a readiness kit before the mammograms, one of many innovative and proven approaches to community health that earned Dennehy a 2012 James Irvine Foundation Leadership Award.

While coming up with creative routes around poverty was difficult, the most challenging part of Sha’s job was engaging patients in their own health care. “An adviser, Dr. Loma Flowers, encouraged us to really break down when and why we were upset during a patient interaction and how we could better address our issues in the future,” says Sha. “That was a crucial part of the residency.”

When she finally made a breakthrough with one resistant patient, she felt transformed. “He was a very, very difficult man with diabetes and high blood pressure, both completely out of control,” Sha recalls. Although he initially came in for pain medication, additional testing indicated he had prostate cancer. “After diagnosing him, I saw immediate changes. We worked together on the cancer and his other problems. He’d take the extra step and say, ‘Hey Vivian, I want to get my scans done now.’” At the end of her residency, he asked if he could follow her to her new clinic. “It touched my heart,” she says. “He was taking charge of his health, and I was part of the change.”

Ryan Ray Dela Cruz works to fill another great void for San Francisco’s indigent population: dental care. Following in his mentor Steve Silverstein’s footsteps, Dela Cruz is directing the School of Dentistry’s Community Dental Clinic (CDC). “Our patients are from disadvantaged backgrounds and have absolutely no other way to obtain dental care,” says Dela Cruz, a third-year student. “A lot of them are recovering drug addicts who are trying to get their lives back together.”

His most poignant moment at the CDC came in the form of a smile, as he worked on a woman with a missing front tooth. “Her mouth was always clamped closed,” Dela Cruz says. Then she received the one crown donated to the clinic each month. “After eight visits, I finally saw her smile!” he recalls. “She was so happy, she was in tears.”

Started by fourth-year dental students in 1993, the CDC is solely student-run, with volunteer faculty supervision. More than 80 percent of dentistry students volunteer at the clinic, performing routine and deep cleanings and filling cavities. Silverstein believes this focus on student involvement is behind the clinic’s success. “The CDC is still around because it’s entirely student-driven,” he says. “If students quit, they’re letting each other down, and they would never do that.” The clinic operates on less than $5,000 annually, receiving basic infrastructure support from Dean John D.B. Featherstone’s office. Together, students donated the equivalent of $87,684 in services during 2011. Although they receive elective credits for their work, the real payment is gratitude.

“I can’t even describe what I get out of this,” says a choked-up Dela Cruz. “Yes, I gain experience running a practice. But honestly, the best part of this job is the thank-yous. The patients are just so appreciative.” They have an especially good reason to be grateful this year: after winning the American Dental Association’s 2012 Bud Tarson Dental School Student Community Leadership Award, Dela Cruz donated his $5,000 check to the CDC’s modest coffers.

School of Pharmacy’s Ryan Ray Dela Cruz

School of Medicine’s Colette DeJong

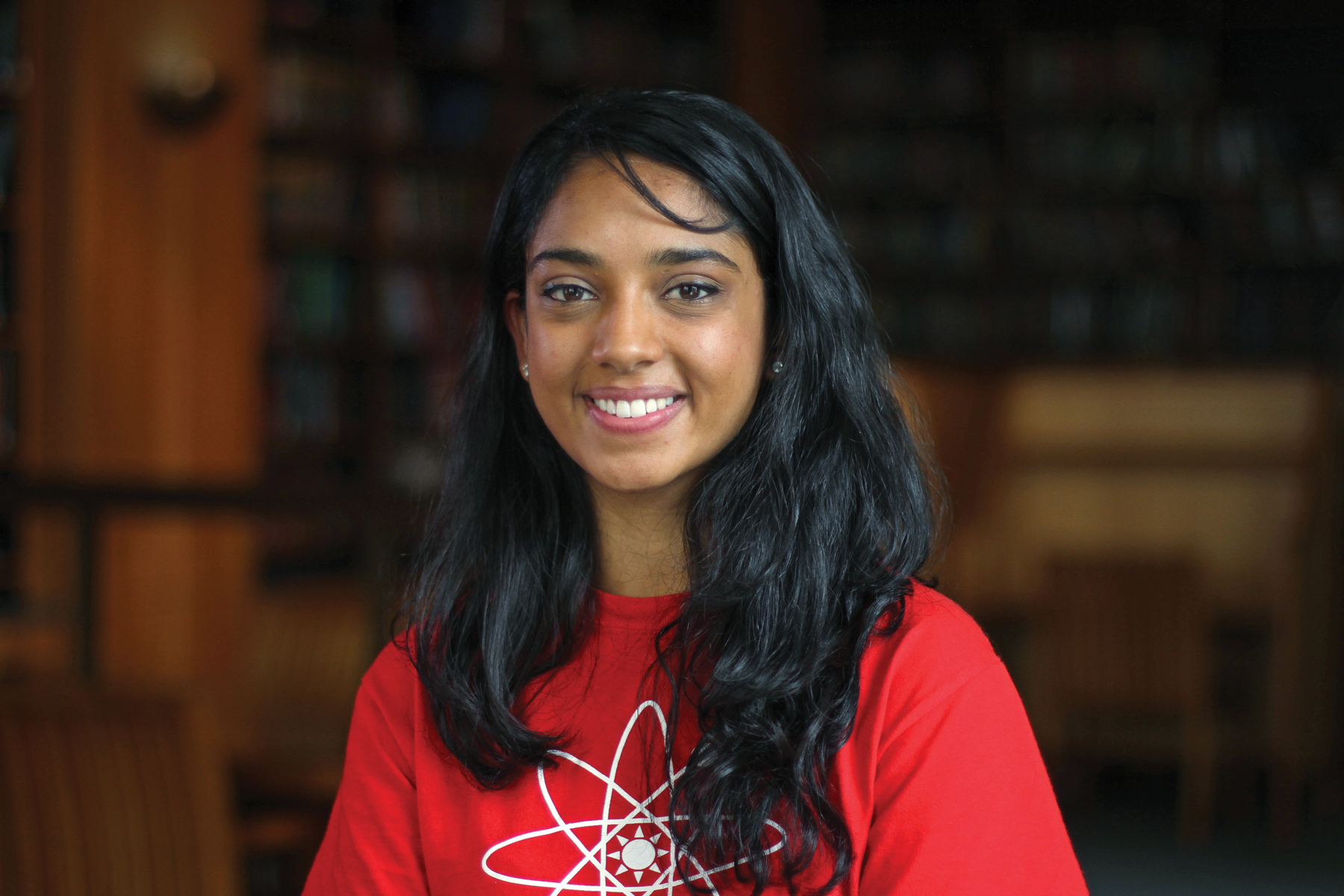

School of Pharmacy’s Tanvi Shah

Though each project has its own inroads to community, they all require commitment from students who are already knee-deep in demanding degree programs. Photos: Jonathan Drum

As with dental care for the poor, the economic recession has also taken a toll on public education in San Francisco. Tanvi Shah, a second-year pharmacy student, and 29 of her fellow trainees try to patch the academic holes by teaching science at Rosa Parks Elementary, an underfunded school in the Western Addition neighborhood. Pharmacy students began volunteering here two years ago, conveying the subject of science in a hands-on, engaging way.

An Otter Pop – a liquid sweet treat that turns to ice in the freezer – is just one of the tools Shah has in her lesson plan, using the pop to impart a fundamental science lesson. “In our States of Matter and Phase Change curriculum, we dip Otter Pops in liquid nitrogen to show the instant change from liquid to frozen,” she says. “The kids love it! They’re amazed.”

Members of the School of Pharmacy’s Science Squad deliver a lesson on circuitry to kids at Rosa Parks Elementary School. Photo: Steve Babuljak

The Science Squad, as Shah and her colleagues refer to themselves, teach six times a year at Rosa Parks; to date, they have educated 100 students from the fourth and fifth grades. The potential impact of their work is twofold. Kids with a background in science may be better able to understand preventive health information and incorporate it into their lives, thereby avoiding many of the health issues that plague underserved communities. What’s more, exposure to the Squad’s science professionals encourages kids to forge their own paths to science careers.

Graduate student Osama Ahmed is also pitching science careers – to minority high school students. “When I started UCSF’s doctoral program in the neurosciences, I took a look around and saw very few minority students,” says Ahmed, an immigrant from Sudan. While in high school, Ahmed completed a minority apprenticeship at Philadelphia’s Monell Chemical Senses Center, realizing the power of outreach programs in the process. “My mentor at Monell told me he believes people just don’t know about science as a career and therefore don’t pursue it,” he says. “So I came up with a radio show where investigators talk, jargon-free, to a mass audience, to get people excited about it.”

The show’s title, “Carry the One Radio,” is both a nod to mathematics and a reference to the notion of lifting people to new heights. Ahmed’s goal is to feature a rich variety of people and perspectives in graduate-level science. “There’s a broad spectrum of races in the U.S.,” he says. “Shouldn’t it be reflected in the sciences?”

Ahmed and his founding partner, Bryan Seybold, another graduate student in the neurosciences, have put together a team of 10 students and a high school teacher to help recruit guest scientists, build the audience, and hone the show’s website. They have interviewed more than 30 scientists so far. “The vast majority have not only been willing but excited to participate,” says Ahmed.

Once he gets the green light to conduct an interview, Ahmed and fellow student Karuna Meda, also a doctoral trainee, pack up a computer rigged with recording software and head to the investigator’s office. Ahmed and Meda ask their subjects to speak in lay terms about their overall research, answer one specific question relevant to their interest, and end with why they chose science as a career.

Graduate students and ‘Carry the One Radio’ founders say UCSF, with its culture of independence, set the tone for creating the show. From left: Bryan Seybold, Karuna Meda, and Osama Ahmed interview faculty member Eric Collisson. Photo: Steve Babuljak

“I think it’s really powerful for kids to hear about how these scientists who are changing the world got to be where they are,” says Ahmed. “By listening to an episode, maybe they’ll get excited and think, ‘Hey, I can do this, too.’”

Seybold sees UCSF as an ideal setting for the radio show. “We’re located in a city of start-ups, at a university that values independence,” he says. UCSF, he notes, is not an ivory tower dominated by a few elite labs. “This is a public institution with many small, powerful labs making things happen, an environment that set the tone for creating the show. We saw a need, and made ‘Carry the One Radio’ happen.”

First-year medical student Colette DeJong, who is enrolled in UCSF’s Program in Medical Education for the Urban Underserved (PRIME–US), chose UCSF for the same spirit of independence that Seybold so values. PRIME is a five-year track for medical students who are committed to working with underserved communities.

“UCSF has a long legacy of social justice with its pioneering work in HIV/AIDS, and it’s situated in one of the most progressive cities in the country,” says DeJong. “I was drawn here because UCSF is making a big effort to give back to its community in lasting and meaningful ways.”

Watch the students discuss why they serve.

PRIME students hit the ground running: during her second week, DeJong was placed on a Hepatitis B working group under the guidance of a “navigator” from the San Francisco Health Improvement Partnership (SFHip), a consortium of community organizers, government agencies, and UCSF clinical scientists. One of four working groups devoted to chronic illnesses that impact communities in San Francisco, the Hepatitis B group is reaching out to the city’s Asian and Pacific Islander population, which is 100 times more likely to contract Hep B than others. The virus, which can be asymptomatic for years, underdetected, and lethal, is responsible for 80 percent of the country’s liver cancer diagnoses.

“San Francisco has the highest rate of Hep B in the nation,” reports DeJong, “and it’s 50 to 100 times more infectious than HIV.”

DeJong is interviewing the major players in the effort to contain the virus, including staff members of the Chinatown Public Health Center; city health workers; UCSF physician and Vietnamese immigrant Tung Nguyen, MD, resident alumnus; and representatives from Kaiser Permanente, which has been very successful in treating its Hep B patients.

I was drawn here because UCSF is making a big effort to give back to its community in lasting and meaningful ways.”

“One of our goals is to get the students out of the classroom, which has an evidence-based perspective, and into the community, to expose them to an ‘eminence-based’ perspective,” says Aisha Queen-Johnson, PRIME’s project manager. “They see what it takes to come together at the table and work on policies and effective interventions, in real time.”

PRIME students learn immediately that doctors are not the sole arbiters of health care. “There’s no medication that alleviates issues with housing, education, lack of access to healthy food, or being unsafe in your home,” says DeJong. “Health care doesn’t start or stop at the doctor’s office doors.”

Physicians in DeJong’s working group have one chair at a communal table that also seats nurses, pharmacists, epidemiologists, public health researchers, biomedical statisticians, and HMO administrators. She is struck by how thoughtful and collaborative the process has been.

“Historically, parts of this group would be in competition with each other,” DeJong points out. “Now they realize that by addressing the problem separately, they won’t make a lot of progress. Working together, they will.”