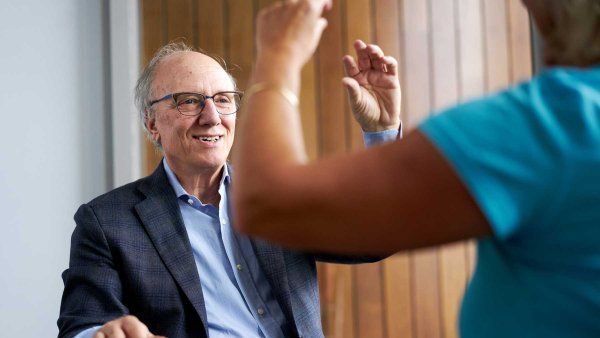

“Magic” is one of those tricky words, tarnished by overuse. It isn’t often that you hear it from the mouth of a scientist, and in the wrong setting it can raise some eyebrows. So when newly appointed UCSF Chancellor Sam Hawgood says something was “magical,” attention must be paid.

In 1981, the Australian doctor had just toured several great hospitals, looking for a place to get some research experience before returning to Melbourne. “My wife, Jane, and I visited departments in Paris, London, Oxford, New York, and Boston – and San Francisco was the last of my stops,” he recalls. Many of those hospitals wanted him, but Hawgood was intrigued by what he’d heard about the groundbreaking work under way in newborn medicine at UCSF.

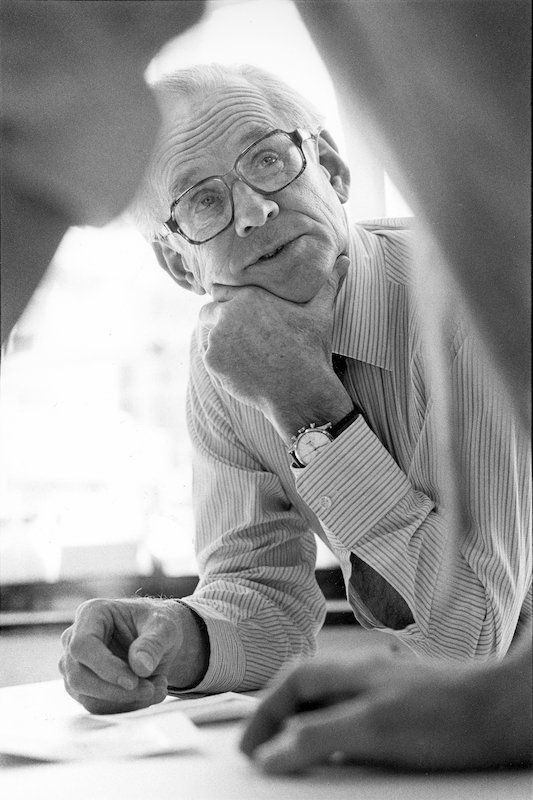

Hawgood met with John Clements, MD, who was conducting research on the respiratory problems of premature babies. “I spent a couple of hours with him, and it was really career changing for me,” says the chancellor, sitting in his office in the Medical Sciences Building on the Parnassus campus. Clements (who is now a professor emeritus of pulmonary biology) later patented a drug to compensate for the lung coating known as surfactant that is missing in infants born with immature lungs; the discovery has saved untold lives and won Clements the Albert Lasker Clinical Medicine Research Award in 1994.

“It was the commonest cause of death, and we had very few tools to overcome it,” recalls Hawgood. “We could put babies one at a time on what were very primitive mechanical ventilators. ...You felt pretty powerless.”

Within months, Sam Hawgood had left Australia – with Jane and their then-two-year-old son – to join Clements’ team. “On the 13th floor of this hospital, just above us, [was this] unusual community of superb clinicians as well as scientists from a number of different backgrounds, from biophysics to chemistry to physiology to anatomy, who clearly respected each other, actually really liked each other, and worked so well together,” says Hawgood. “They would work with you even if you didn’t have a clear understanding of their skill sets.

“For me it was sort of a magical experience,” he adds.

Aussie Roots

Hawgood had come to medicine through science and human biology. His parents were pharmacists; an office below their house was occupied by a doctor; and his first interest, growing up by the coast in Queensland, was marine biology. “But when I looked into career paths of marine biologists in Australia in the ’60s,” he recalls, “I think there were two or three employed, so it didn’t seem too encouraging.”

In Australia at that time, students went straight from high school to medical school, “so it was a decision I had to make at age 16.” He matriculated as a premed at the University of Queensland in Brisbane and had what he calls “a typical student experience.” Meaning? “I got into all sorts of fun and trouble,” he says with a slight smile. “I’d come out of an all-boys boarding school into a world I didn’t know about.”

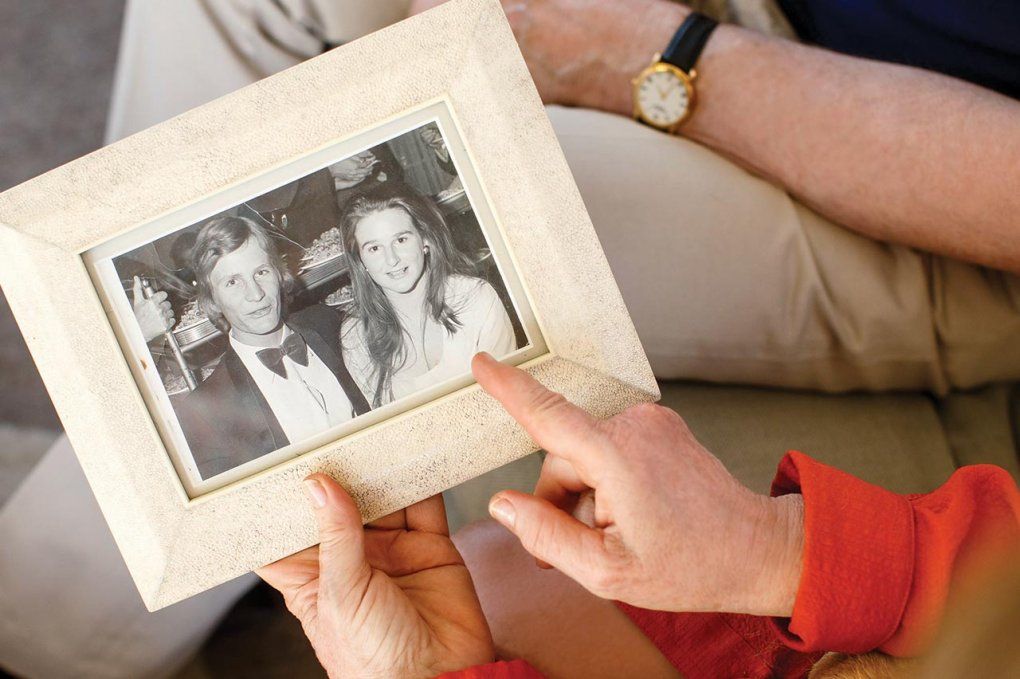

Sam and Jane Hawgood met while attending the University of Queensland in their native Australia. Photo: courtesy of Hawgood family

It was there he met Jane, who has been his partner for more than 40 years. “She was doing social work and had been at university for a year, just a little ahead of me. So she was an experienced older woman.”

“We had a system where older students were given two younger students to mentor,” Jane Hawgood recalls. “I got Sam and his best friend. The mentoring in those days consisted of playing cards in my room on Sunday night. But honestly, it was kind of like love at first sight for me.”

The two were married after he finished medical school, and he did his residency training (“to be honest, my first year [I picked] the hospital more for the quality of the surf than the medicine”) before traveling with his new wife to Hong Kong, where the two worked in the New Territories for a year. The experience was profound for them both, as they served a poor populace with limited access to health care. “You got to see a lot of medicine you wouldn’t see in Australia at the time,” recalls Hawgood.

On meeting John Clements, MD, at UCSF in the early 1980s: “I spent a couple of hours with him, and it was really career changing for me,” Hawgood says. Photo: David Powers

The Hawgoods traveled extensively throughout South and Central Asia before returning to Australia, where he entered pediatric training and soon became fascinated with the specialty of newborn medicine. His interests in the new and changing field were as much personal as intellectual.

“It was that combination of having to have a really deep understanding of developmental biology and normal development, and then overlaying it with the development of the disease process, that was very stimulating,” he says. And the subspecialty burnished his people skills. “While babies have their own personalities,” he says, “as a newborn medicine specialist I learned what an intense period it is for the family.”

At UCSF, Hawgood found he was good at working with parents, and he credits his wife for her guidance. “I think Jane helped me very much on that; she’s an incredibly skilled observer of the human condition,” he says. “Once we decided to stay [in San Francisco], and she decided to think about her own career, she worked in the AIDS clinic here in the late ’80s, when the epidemic was just at its height.”

“We didn’t have anything called self-care in those days,” says Jane. “I had young kids and was really busy. After an emotional day at work, I would get home and start in on a project around the house. I realize now what I was doing was just reflecting on the day.”

Tapped to Lead

Her husband’s career began to morph as well, as he went from vice chair of pediatrics to interim chair, with a promise from the then-dean of medicine “that he would do a quick search and I could go back to doing what I loved doing at the time, which was leading the division of newborn medicine.”

Sam Hawgood on the job at UCSF Medical Center in 1997. Photo: courtesy of Hawgood family

Instead, in 2004, he was made the chair of pediatrics and was, he recalls, “happy doing that, assuming that was what I was going to be doing for the rest of my career.” Until he was asked to serve as interim dean of medicine by then-Chancellor J. Michael Bishop, MD, “who again said he would conduct a quick search so I could go back to doing what I loved doing.”

Hawgood held the interim post for 18 months before being appointed dean in September 2009 by then-new Chancellor Susan Desmond-Hellmann. When she left (to be CEO of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), Hawgood was made interim chancellor on April 1 – “April Fool’s Day,” he notes.

“I have the world’s greatest experience as ‘acting’ and ‘interim,’ ” Hawgood says with a laugh.

According to his wife, Hawgood “has a lot of humility and a lot of integrity, and you see how in love with this place he is,” she says. “I think that’s what really got him in this leadership position.

“He’s such a quiet man,” Jane adds. “When he wants to talk, I will always stop what I’m doing because he’s not a guy who talks a lot, but when he does, it’s so lovely to hear what he’s thinking inside.”

Hawgood’s career path (unimaginable when he was a young pediatrician, he says) was a good way to learn. “As a chair, you work pretty closely with the dean, so you have a reasonable sense of what being a dean is, but until you actually do it you don’t know all the nuances.”

His interests have always been eclectic, and while he is winding down his own lab work (he still manages a research lab but says, given his new day-to-day demands, he will close it at the end of this grant cycle) and is no longer working with patients, he took to the administrative side of academe handily. “This is probably a pretty sad statement, [but] I can get as excited by the mechanics of a financial spreadsheet as I can from understanding how a cell functions,” he says. Even when he was working in the newborn ICU, he was interested in the context within which he worked and would ask the hospital’s CFO to explain the unit’s financial structure.

“What I’ve learned over the last 30 years is that if you’re interested in someone else’s domain of expertise and express that interest in a real way, then people are just delighted to help you,” he says.

Family Matters

His wife’s career has been equally protean, moving to a concentration on palliative care for the last 10 years. She finally retired in June, after 42 years as a social worker, but her retirement is busier than many people’s careers; she is still a passionate member of the Zen Hospice Project board and worked hard to re-establish that project’s collaboration between the hospice (which had been closed for earthquake retrofitting and then lack of funding) and UCSF.

The Hawgoods relax with one of their dogs on the back porch of their home. Photo: Steve Babuljak

They have two grown sons: Andy, the eldest, is a graphic designer in San Francisco, and his brother, Alex, left his job at the New York Times (though he still writes about cultural affairs for the paper) to be part of a fashion start-up in Manhattan. Their reaction to Alex’s career move, according to Hawgood, would not surprise most parents: “Really? You have health insurance, you have a job. ... But we are very proud of their accomplishments and how they are leading their lives,” he adds.

And while his wife still goes back to Australia every year, the chancellor has no second thoughts about the move he made over 30 years ago, though he speaks with admiration of the Aussie work atmosphere: “It’s a much more relaxed approach to life, while at the same time there’s a lot of high achievement there,” he says.

But there is finally a meaning to his trajectory, at least one that Hawgood sees now.

“What I didn’t fully appreciate when I came here was that the environment that allowed me to thrive was not an accidental environment,” he says. “It wasn’t magical by magic; it was magical because there were administrators – directors of the cardiovascular research institute, chairs of the department of pediatrics, deans of the school of medicine, chancellors – who were devoting their time to make it a magical place.

"It feels like at this stage in my career that it’s an evolution. Now my responsibility – without being heavy-handed about it – is to create an environment behind the scenes so that the equivalent of me coming here at 30 years of age can say, ‘I don’t know why, but this is a magical place.’”