Cronutt must be the world’s luckiest unlucky sea lion. His misfortune: domoic acid poisoning from oceanic algae blooms; the toxin causes seizures like those of adult human epilepsy. Scores of marine mammals along the West Coast are similarly affected every year; they suffer a 60% mortality rate.

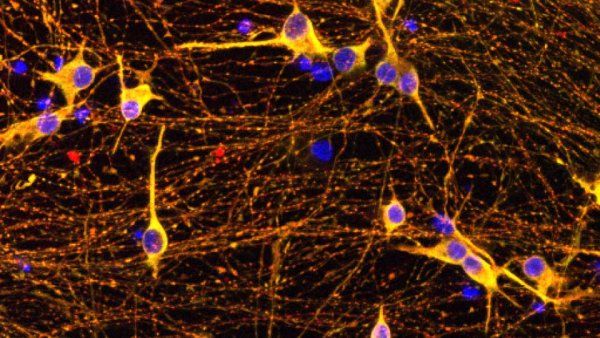

Cronutt’s good fortune? The pioneering work of Scott Baraban, PhD, UCSF’s William K. Bowes Jr. Professor of Neuroscience Research. Baraban developed a procedure for harvesting and transplanting embryonic brain cells into epileptic mice, inhibiting seizures in the rodents and restoring their diminished cognitive and physical capabilities. In collaboration with the Marine Mammal Center (MMC) in Sausalito, Baraban explored trying the treatment on San Francisco Bay’s stricken sea lions.

By the fall of 2020, Baraban and his colleagues had developed the necessary equipment to deliver a precisely targeted injection of cells into an afflicted sea lion’s atrophied hippocampus. The plan was to optimize the procedure on a sea lion cadaver before treating a live animal. Then Baraban got an email from veterinarians Claire Simeone and Shawn Johnson at Six Flags Discovery Kingdom in Vallejo, Calif.

Rescued more than once by the MMC after stranding himself on land, and then adopted by Six Flags, 7-year-old Cronutt was disoriented and having increasingly frequent and severe seizures. He’d stopped eating and had dropped nearly one-third of his body weight. He was going downhill quickly. Could Baraban try the world’s first interneuron cell transplant treatment in a higher mammal under a “compassionate use”-like trial?

“We didn’t know if he would survive the surgery, much less what the outcome would be, ” says Baraban.

Cronutt receiving cell transplant surgery in October 2020. Photo: Shawn Johnson

Cronutt has not had any seizures since his surgery and is back to a healthy weight. Photo: Dianne Cameron

On Oct. 6, 2020, a team of 18 veterinarians, researchers, and neurosurgeons gathered outside a veterinary clinic in Redwood City, Calif. Mariana Casalia, PhD, a neuroscientist in Baraban’s lab, had the embryonic neural pig cells she’d prepared waiting on ice. Cronutt was anesthetized and intubated in the parking lot. From there, Baraban watched the procedure on a Zoom feed, since COVID-19 distancing protocols prevented more than five people from being in the operating room. Five hours later, Cronutt emerged from anesthesia and was on his way home.

The weekend before the procedure, Cronutt had close to a dozen seizures. Since the transplant? None. He’s back at a healthy weight, too, and while he will likely have long-term mental health challenges from the algae toxin, “he’s doing very well,” says Dianne Cameron, the director of animal care at Six Flags. “He’s learning new things, using his flippers correctly, knowing right from left. He has a higher tolerance for when he gets confused.”

Cronutt no longer needs his regimen of Valium, steroids, and antibiotics and is tapering off his antiseizure medication. He could have a life span typical of a sea lion under human care, living into his 30s – nearly twice as long as pinnipeds in the wild and a far cry from the “humane euthanasia” he was facing pretransplant.

“Cronutt looks very similar to epileptic rodents we’ve transplanted over the past 10 years, where we consistently observed dramatic therapeutic benefits,” says Baraban, who visits Cronutt regularly and monitors his progress.

Baraban hopes to continue offering his lab’s unique expertise in harvesting and preparing embryonic pig cells to help more sea mammals, which are increasingly at risk as climate change warms the world’s oceans, making algae blooms more common.

Encouraged by their success treating Cronutt, the Baraban laboratory is refocusing its interneuron transplantation research from embryonic mouse cells to embryonic pig cells, which have properties closer to those of higher mammals.

“There’s a lot we’re investigating – how the cells get to where they go, how they make connections, and how they communicate in the host brain,” Baraban says. “While cellular therapies for people with epilepsy won’t be available next year, we’re very excited about the long-term clinical potential of this work.”