The Case of the Suspicious Swelling

A grandmother showed telltale signs of a common endocrine disorder. But a puzzling lab result put the detective skills of physicians Joan Addington-White and Rob Weber to the test.

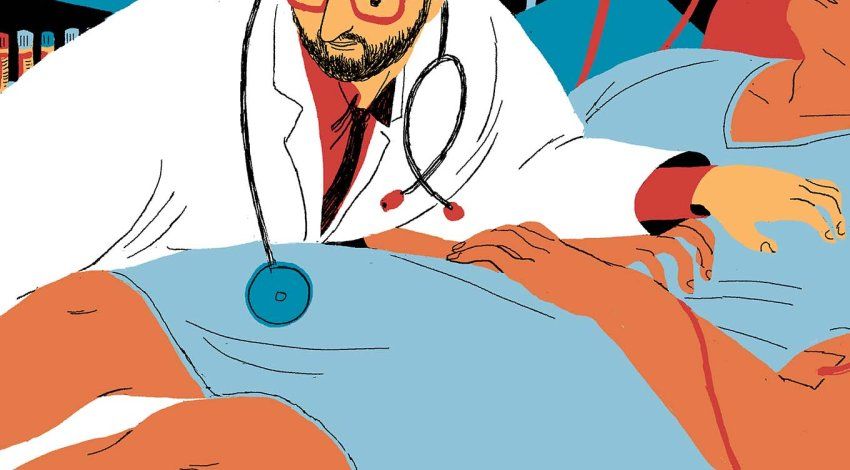

A woman in her mid-50s arrived at an outpatient clinic at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital complaining of swelling in her legs. “When I walked in the room, I realized I had seen her before,” says Joan Addington-White, MD, the physician on call.

The patient had visited the clinic a number of times before. But this time, she looked strikingly different, thought Addington-White, who is a UCSF professor of medicine and the residency director of the hospital’s primary care internal medicine training program. The patient showed her a year-old photo on her phone that confirmed Addington-White’s memory: She had been much thinner and strong enough to stand and hold her 2-year-old grandchild. Now, her whole body was swollen, and she needed a wheelchair to get around.

Upon conducting a careful physical exam, Addington-White noted high blood pressure, a rounded face, new body hair growth, a fat deposit on the patient’s upper back, abdominal stretch marks, and thin – almost translucent – skin. This constellation of symptoms is characteristic of Cushing’s syndrome, an endocrine disorder caused by excess levels of steroid hormones such as cortisol – often due to an adrenal or pituitary tumor or the long-term use of steroid medications.

Addington-White called on Rob Weber, MD ’19, PhD ’17, then a resident in internal medicine, to admit the patient to the hospital, confirm her steroid levels, and track down their source. The medical team asked about her current medications and supplements, but the list she gave didn’t include any steroids. And when they tested her cortisol levels that night and again in the morning, the results shocked them. “Her cortisol was zero,” Weber says. “That didn’t make sense.”

Then came an unexpected clue: The patient complained of shoulder pain and asked for some pills she had at home but hadn’t mentioned before. Weber’s ears perked up, and he asked the woman to elaborate. Since tearing her rotator cuff a year earlier, she said, she’d been taking an unregulated arthritis supplement from Mexico. Weber’s team asked her family to bring the pills in so they could examine them.

The bottle’s ingredient list was fairly benign: vitamins, collagen, glucosamine, curcumin. But an online search turned up articles in Spanish warning that the supplement often contained unlabeled ingredients, including steroids. Sure enough, analysis revealed the pills contained high doses of dexamethasone, a synthetic steroid. Weber’s team also found dexamethasone in the woman’s blood; the drug can suppress the body’s cortisol production, explaining why her supply was nil.

But abruptly stopping a high-dose steroid can send the body into shock, so the team prescribed a tapering regimen. Although Cushing’s syndrome is typically reversible, the woman’s ongoing treatment is complicated by additional health problems, including severe degeneration of her shoulder and hips – likely caused by the high-dose steroids. She is on the road to recovery, her doctors hope, though it may be a bumpy one.