Looking back, Mary suspects her symptoms started in childhood. An Air Force brat, she grew up in Oklahoma, France, Greece, and New York before settling in Northern California, where she still lives with her husband. “I was just a sick kid,” she recalls. Her muscles constantly ached and spasmed, and she had terrible allergies. “There was always something wrong with me,” she says.

Then, at 18, she injured her back in a car accident. Despite intensive therapy, the pain only worsened. It spread down to her pelvis and all the way up to her shoulders and neck. She’d get charley horses – one after another, like a bout of hiccups – that took her breath away. Meanwhile, she went on to build a career in the insurance industry and had children and grandchildren.

Decades passed, but her health troubles didn’t. Instead, they multiplied. Trouble breathing. Trouble swallowing. Trouble holding onto things. Her fingers would go numb and pinch together like lobster claws. She took painkillers. She went to a chiropractor. She got injections and had surgeries and started using an oxygen tank. “I saw every specialist you can think of,” says Mary, now 72. “Cardiologist, pulmonologist, nephrologist, neurologist… Nobody had an answer.”

Her resolve to find one would eventually lead her to UC San Francisco, which, in 2022, opened a new diagnostic clinic at the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences for people with puzzling neurological symptoms. The Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Neurology Clinic, named for the philanthropists, gets hundreds of calls a year from patients across the country hoping to finally end their diagnostic odysseys. Of the nearly 300 patients the clinic has seen so far, more than half have received a diagnosis – a remarkable rate, considering that many of them had been chasing one for years. “We see a lot of people on their second, third, or fourth opinions,” says Maggie Waung, MD, PhD, the clinic’s founding director.

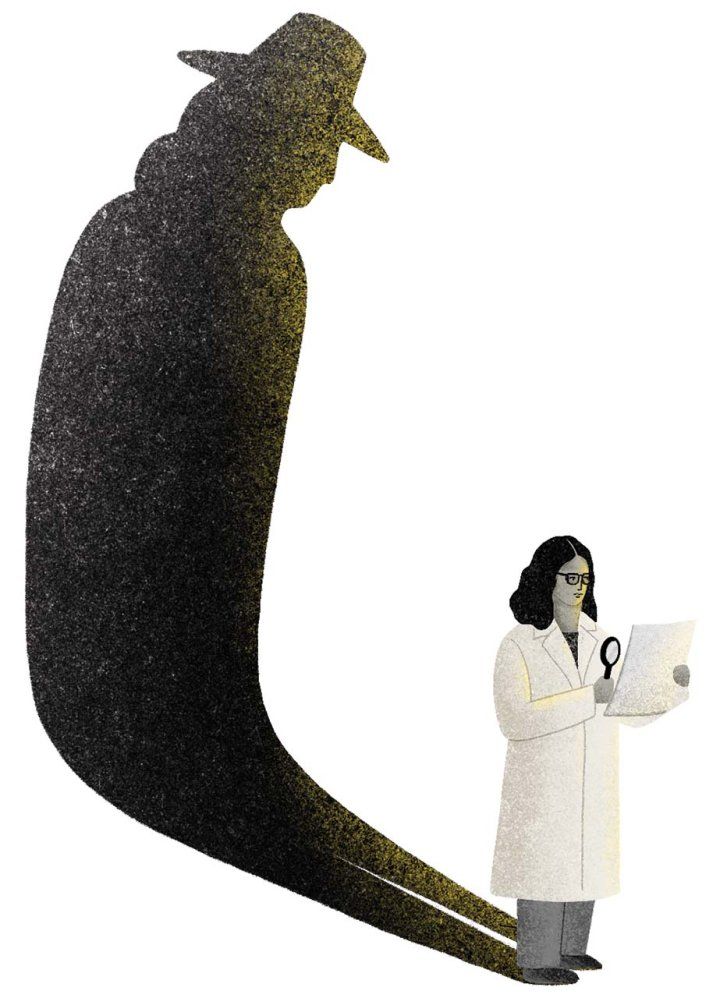

Waung, who also holds one of four UCSF professorships endowed by Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem, understands such patients’ agonizing journeys better than most. She went into neuroscience because she’s always been drawn to mysteries – as a girl, she devoured Nancy Drew books and Agatha Christie novels – and the brain is one of the greatest mysteries of all.

After completing a neurology residency at UCSF in 2014, Waung joined the faculty and started a research lab studying headaches. In the years that followed, both of her parents developed rare neurological disorders. Waung didn’t know it then, but their struggles to figure out what was wrong and to get the right care – bouncing from one doctor to the next, undergoing test after test, fighting with insurers, not being believed – would mirror the experiences of dozens of patients who’d later come to her clinic.

No one was stepping back and thinking about the big picture.”

Her parents’ illnesses and eventual deaths changed the course of Waung’s career. “With both my mom and dad, I remember just wanting someone smart to put it all together,” she says. She began feeling frustrated with the state of neurology, which, like other medical fields, was growing increasingly specialized and fast-paced; doctors were ordering more tests but spending less time with patients. “I felt like things were moving in the wrong direction,” Waung says. As a neurologist herself, she understood the urgency to accommodate the rising number of patients and knew that many cases could be resolved quickly. But she worried that the most complex cases, like her parents’, weren’t getting the scrutiny they deserved. “No one was stepping back and thinking about the big picture.”

Well then, she decided, I will.

A study in sensation

The Manetti Shrem Clinic is on the first floor of the Joan and Sanford I. Weill Neurosciences Building, a luminous glass mid-rise on UCSF’s Mission Bay campus. When I visited in January, the lobby was still dark and quiet. Patients weren’t expected to start arriving for another half hour.

I wandered down a hallway looking for Waung, who had invited me to sit in on some of that day’s appointments. Her office door was shut, but I could hear typing. I knocked softly. There was no answer, so I knocked again. After my third attempt, the door cracked open.

“Hi. Sorry,” Waung said, continuing to type, her eyes glued to the computer screen. “I just got a breakthrough on a case, so I was just messaging…” Her voice trailed off as she finished her note. I glanced around her small office. Above her desk hung a Chinese landscape painting that, she mentioned later, her father had given her. In the wintry mountain scene, bamboo trees bow under their burden of snow – a symbol of the resilient scholar who bends but does not break.

The case she was working on, it turned out, concerned a patient named Matthew. He’s 44 and teaches drama at an East Bay elementary school. He’d started accumulating “very odd symptoms” the previous April, he later told me. First, he lost some vision in one eye for about a week; not long after, he began having dizzy spells. “It usually started with a massive headache,” he says. “The only thing that would make it better was to lie flat in the dark.” Acupuncture seemed to help, and by July he thought he was back to normal – but then he realized he couldn’t feel half his face.

He tried to get an appointment at UCSF’s regular neurology clinic but was told there wasn’t any availability for months. When I mentioned this to the chair of the neurology department, S. Andrew Josephson, MD, he was regretful but not surprised. Like most of medicine today, he says, neurology has a “huge shortage” of doctors. The situation is particularly dire in rural areas. UCSF has tried to fill the gap by expanding its clinical faculty so as to be able to help patients from well beyond the Bay Area who would otherwise “fall through the cracks,” says Josephson, the Castro Franceschi and Mitchell Distinguished Professor. But that hasn’t fixed the underlying problem, which is that demand for care is dramatically outpacing capacity everywhere.

Waung says she keeps an ear out for patients like Matthew, whose symptoms are rapidly progressing. “It’s not bad enough where they need to go to the ER, but they can’t wait three months for an appointment,” she explains. How to identify those patients, though, is a catch-22: The doctors most qualified to evaluate them and make a referral to her clinic are the same doctors who are booked up. Matthew (who, like Mary, prefers to go by his first name) ended up going to the emergency room just to get a neurology consultation quickly. “I was getting impatient,” he says.

Concerned he might have multiple sclerosis, the ER neurologist put Matthew in touch with Waung. When he met with her at the Manetti Shrem Clinic, what impressed him most was her attentiveness. “She was with me for two hours,” he says. “She never left the room. Every single human I’ve told that to is like, ‘What?!’”

Waung performed a lengthy physical exam – checking the fitness of Matthew’s muscles, nerves, and brain – and talked through his medical history. She then asked him a question that would crack open the case: “Has anything else ever happened to you that’s not in these records?” Matthew flashed back to when he was 13 and gravely sick with a “mystery case” of meningitis, a catchall for a swelling of the tissues surrounding the brain and spinal cord. The condition eventually subsided on its own, and no culprit was ever found.

Waung suspected that episode 30 years earlier was a flare-up of the same malady now rearing its head again. “It never would have crossed my mind to make that connection,” Matthew says. After a battery of tests ruled out multiple sclerosis and other more common conditions, Waung ordered an antibody screen that confirmed her hunch. The result had popped into her inbox on the morning of my visit: a positive hit for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease (MOGAD), a rare inflammatory disorder that can be managed with steroids or other immune-modulating therapies.

“It makes sense because MOGAD often presents in children,” Waung told me. Her voice, as always, was soft and measured, but she was clearly excited. “It’s one of those diseases that can be quiet for a long time.”

When Matthew learned of the diagnosis that evening, he felt mostly relief. “It had been almost nine months of not knowing what was wrong and feeling like I was crazy,” he says. “Just having reassurance that it’s something real and treatable – I didn’t know how valuable that was until I didn’t have it.”

In the genes

Soon, Waung hurried off to greet her first patient. I sat down at an empty workstation and waited for medical geneticist Joyce So, MD, PhD, a collaborator of Waung’s whom she’d arranged for me to shadow.

Once a month, So and her team of genetic specialists see Manetti Shrem patients who are suspected of having neurogenetic disorders. The service is an offshoot of UCSF’s Adult Genetics Clinic, which So was recruited from the University of Toronto to start up in 2019. Also UCSF’s Epstein Professor of Human Genetics, So believes that many neurological mysteries can be solved by genetics. When I interviewed her later, she pointed to a 2023 study of more than 1,400 patients with unexplained neurological illnesses, which found that 10% had a genetic root. Because the study looked at only 725 genes, the real percentage is probably even higher, she argues.

I didn’t have to wait long before So swooped into a chair beside me, sweating and out of breath. “Of course today’s the day when public transit decides to go kaput,” she huffed, dumping her ID and phone, plus a stethoscope and reflex hammer, on her desk.

After she’d collected herself, I followed So and genetic counselor Sawona Biswas, MS, to back-to-back appointments. One patient, a former athlete sporting a North Face fleece, complained of burning pains in his legs and could barely walk. His condition had eluded a diagnosis for eight years.

“He’s a unicorn,” noted his sister, who had come with him.

“I’d rather not be unique in this way,” he said, despondently. He had hoped a genetic test would at least give his affliction a tangible shape. But he’d just been tested for several gene variants linked to neuromuscular diseases, and nothing had come of it.

So says that patients often think DNA testing will provide an easy “yes” or “no”: You either have a bad mutation or you don’t. In reality, genetic analysis is complex. Experts customarily test for between one and 1,000 or so mutations at a time, and the type of test they order depends on the suspected diagnosis, she explains. For that reason, patients who have many seemingly unrelated symptoms or who develop new symptoms over time can be sent down testing rabbit holes. Zeroing in on the miscreant code – if it even exists – frequently takes years.

More comprehensive tests, like whole exome or genome sequencing, could shorten this diagnostic quest by offering a “one-stop shop” for millions of gene variants, So says. But to her eternal frustration, most insurers refuse to pay for any neurogenetic testing for adults, and so most patients opt for cheaper one-offs, if they can afford them at all. “Coming from Canada, I was so naive,” she says. “I was telling patients, ‘I’m sure we can get you covered because we need it for a diagnosis.’ Boy, was I wrong.”

Medicare and Medi-Cal, she quickly learned, often cover genetic tests only for cancers or in kids, “which is ridiculous,” she says. “As for the commercial policies, they’re all over the map. Some of them explicitly state that the reason for denial is that there’s no evidence for the utility of testing in adult populations.” Fed up, she decided to gather that evidence herself and teamed up with Waung to recruit patients from the Manetti Shrem Clinic for a study that’s now underway.

Examining the athlete, So observed a “pattern of muscle weakness in the lower extremities” and “very active reflexes.” His chart also noted bladder and bowel issues. “When we put all that together, I wondered about adult polyglucosan body disease,” So said. She prescribed a test for another dozen or so genes. If that, too, led to a dead end, then they could “look at rarer things,” she told him.

“Sometimes it’s a quick road, but sometimes it takes longer,” she said.

Plot twist

Then there was Mary. She and her husband had driven five hours early that morning from their home in the Sierra foothills to get to the clinic. Seated beside him in the exam room, she wore a billowy flowered dress and nail polish in various shades of blue.

For most of her adult life, Mary had chalked up her bad back and other baffling symptoms to the car accident she was in as a teenager. Then one day, about 20 years ago, a cousin casually mentioned that he and his children had been diagnosed with myotonic dystrophy, a rare heritable disease that causes the muscles to slowly waste away.

At first, Mary didn’t think much of it. But over the years, as more family members came forward with the same diagnosis, she grew convinced she must have the disease, too, and decided to get tested. “I needed to know if I could have passed it on to my grandchildren,” she told me.

Genetic disorders, So says, usually have telltale flags, including atypical onset, progressive or unrelenting symptoms, complications involving multiple body systems, and a family history. But many doctors don’t know to look for those patterns. “On one end of the spectrum, physicians will see a patient with neurological issues that develop over decades and not have even a lick of suspicion that there could be a genetic basis,” she says. “On the other end, there’s over-suspicion, where people try to ascribe everything to genetics.”

Mary’s case ticked all the boxes. Plus, she had the luck of already knowing her relatives’ mutation. For So, that was the obvious place to start. The week before Mary’s appointment, however, her test for myotonic dystrophy had come back negative.

“I truly was shocked,” Mary says.

So was too. “I have to tell you, this is a real puzzle,” she said to Mary in the exam room. In fact, she and Biswas, the genetic counselor, had been so certain the result was a mistake that Biswas had persuaded the lab to rerun her blood sample, but no dice.

Still, So knows genetic diseases can be tricky. The same mutation, for instance, can cause vastly different symptoms: For example, mutations in the SCN2A gene, which So herself has studied, can variably give rise to seizures, coordination disorders, intellectual disability, autism, and schizophrenia. Conversely, syndromes that look like the same disorder can stem from different underlying mutations, even within the same family. “We see families with multiple genetic disorders all the time,” So told me. Perhaps Mary was another unicorn.

Before investigating other suspect genes, though, So wanted to send a new sample to a different lab to see if it might catch something the first lab had missed. In the meantime, she advised Mary to see Waung, who could test her muscle fibers for other clues.

“We’ll get to the bottom of this one way or another,” she promised.

How cases are cracked

When Waung and her colleagues were planning the clinic, they’d assumed that most cases would be like Mary’s – peculiar plights that would demand a Sherlock Holmes-level of deductive ingenuity. “Going in, we suspected they were all going to be these very complex, rare conditions,” Josephson says. “There’s a lot of those, but there’s also a lot of patients who, it turns out, have very common neurological diagnoses.”

Why they weren’t easily identified elsewhere, Josephson believes, comes back to the widespread deficit of neurologists as well as a lack of proficiency among medical providers generally in assessing neurological problems. “Neurology is one of those fields that non-neurologists find particularly mystifying,” he says.

Jessamyn Conell-Price, MD ’15, MS, one of the clinic’s neurologists, says that about 30% of her cases end up being “just an atypical presentation of things I know well.” Many, for instance, have been unusual forms of Parkinson’s. While the disease is most easily recognized by tremors, subtler signs can include bad constipation and frequent fainting. Previous diagnoses and treatments can also be confounding, Conell-Price says. “You have to tease out the side effects and complications from other diseases that might be obscuring the picture.”

Sometimes, the clinic’s neurologists work out what’s wrong with a patient before even seeing them. “We spend a long time going over the history and prior workups,” says Min Kang, MD, who specializes in neuromuscular diseases. These records, which the clinic’s administrative staff meticulously compile, often span decades and multiple institutions. Their comprehensiveness, Kang says, is extraordinary. Referrals to her general practice, by comparison, can be laughably cryptic – merely “back pain,” for example – in which case she must fill in the backstory herself and redo tests she can’t easily track down. “It’s a dream to have all the pieces already assembled for you,” she says.

Other times, the key to unlocking a difficult diagnosis is simply a detailed physical evaluation, says Alexandra Brown, MD, another staff neurologist and the medical director of outpatient neurology at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. “Neurology is the only medical specialty where we examine literally head to toe.” Done well, she says, this takes 20 minutes or more – time that doctors today rarely have. “It’s an art that, sadly, medicine is losing.”

When I spoke with her in January, Brown, who holds another of the Manetti Shrem Professorships, had just resolved a case that proved her point. Eric Zhang, a 59-year-old grocery clerk in San Mateo who’d had a series of falls, had been searching for an explanation unsuccessfully for two years. One doctor had suspected Parkinson’s. Another guessed multiple sclerosis. Yet another wondered if he’d inherited a rare spastic disorder.

He’d gotten the million-dollar workup, but at the end of the day, all he really needed was for someone to do a thorough neurological exam.”

“He’d gotten the million-dollar workup,” Brown says. “But at the end of the day, all he really needed was for someone to do a thorough neurological exam.” Tapping and pricking and inspecting every inch of his body, she detected a subtle change in sensation within a narrow strip of skin that extended all around his upper chest and back. This meant something was probably compressing his spinal cord at that level. “Most neurologists doing a cursory exam would have easily missed it,” she says. Sure enough, an MRI scan revealed a mass, which a surgeon removed.

“I feel pretty good,” Zhang told me five weeks after the surgery. “In the afternoons, I go outside and take a walk and do some exercises” – activities he hadn’t been able to enjoy for years. “Dr. Brown is an excellent doctor,” he wanted me to know. “She found the root cause of my condition after so many others couldn’t.”

The long game

Before I left the clinic, Waung told me about one last case, which she was preparing to present at an upcoming neurology conference.

About a year ago, a Bay Area couple named Maureen and David Costello had brought in their adult son, Daniel, who lives with them. As a child, Daniel had been slow to walk and never learned to speak beyond simple phrases. He had a knack for math but struggled with attention and spatial reasoning. Occasionally he’d explode in rage, though he was otherwise sweet and kind. Despite years of evaluations by countless doctors, nobody could tell them what troubled their son. “I really thought we would never have an answer,” Maureen told me later.

Surmising a rare genetic disorder, Waung offered to enroll Daniel in the study she’s doing with So. This would allow their research team to parse his entire genome for suspicious DNA changes, including lesser-known ones, as the study would take care of the testing costs, which Daniel’s insurance wouldn’t cover.

When the team reviewed the data, one result stood out: a “variant of unknown significance” in the SATB2 gene. Several mutations in this gene are associated with Glass syndrome, which causes symptoms like Daniel’s. But this mutation was a new clinical discovery. It was also new to his family – neither parent had it.

The Costellos got the diagnosis last August, on Daniel’s 31st birthday. “To be able to pinpoint this as what he has, and it just pertains to him – it was just a huge relief,” David says. At the time, their daughter was eight months pregnant. They didn’t have to worry whether their grandchild might have inherited the disease.

What Waung likes about this case is that it shows the value of persistence. Even when doctors “take a deep dive into a case and try to leave no stone unturned,” she says, they often will abandon it when they don’t find anything. But patients’ stories are constantly evolving, and science is constantly revealing new stones to turn over. When Daniel was growing up, the tools and knowledge to identify his mutation didn’t yet exist. If the Costellos hadn’t kept up the search for 31 years, who would have?

Once a year, Waung and her staff review the clinic’s unsolved cases to see if a new discovery or test might lead to a new break. Although many patients still don’t have a definitive diagnosis, Waung thinks they shouldn’t have to continue on their odysseys alone. “The whole idea is that we’re going to keep looking,” she says.

When I last heard from Mary, she was still optimistic about her own case, despite its stubborn perplexity. A second myotonic dystrophy test had also come back negative, and Waung’s assessment of her muscles confirmed no electrical signature of the disease. Waung had recommended she repeat the muscle exam in a few months and referred her for an MRI to look for marks of nerve damage and autoimmune disease.

I thought Mary would be discouraged, but she wasn’t. “It wasn’t like, ‘Oh, this test was negative – sorry, there’s nothing we can do for you,’” she says of Waung and her colleagues. “I really believe they’re going to figure it out.”