The circular marks – dark rings around lighter centers, where embers burrowed into flesh – are from cigarette burns. The serpentine welts branching four ways – like tributaries of a river – are from lashings with an electrical cable, its four braided wires unraveling at the ends. The glossy patches of skin are from a dousing with caustic chemicals, the butterfly-shaped blotches from an electrocution, the shallow gouges from the blade of a machete.

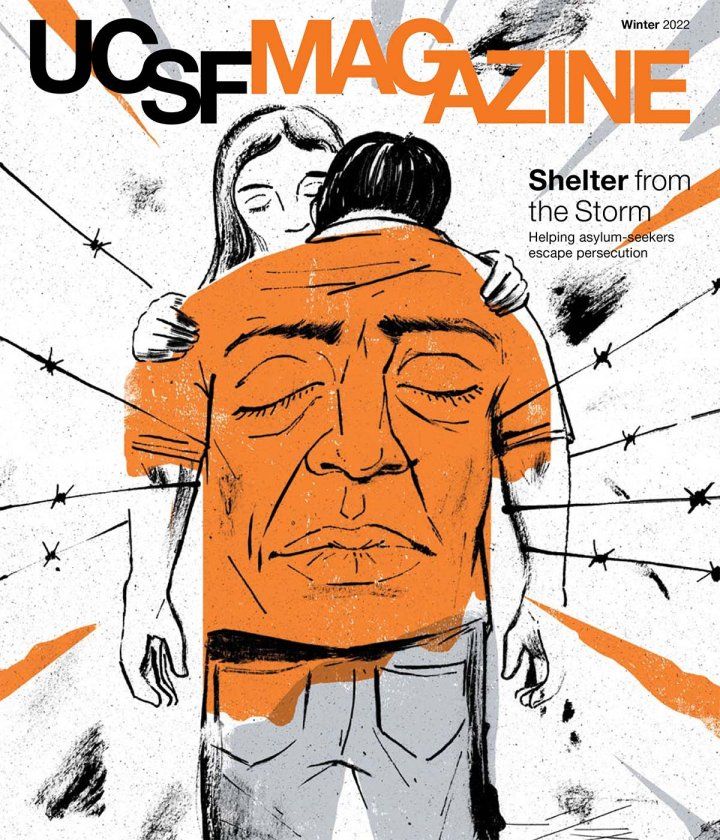

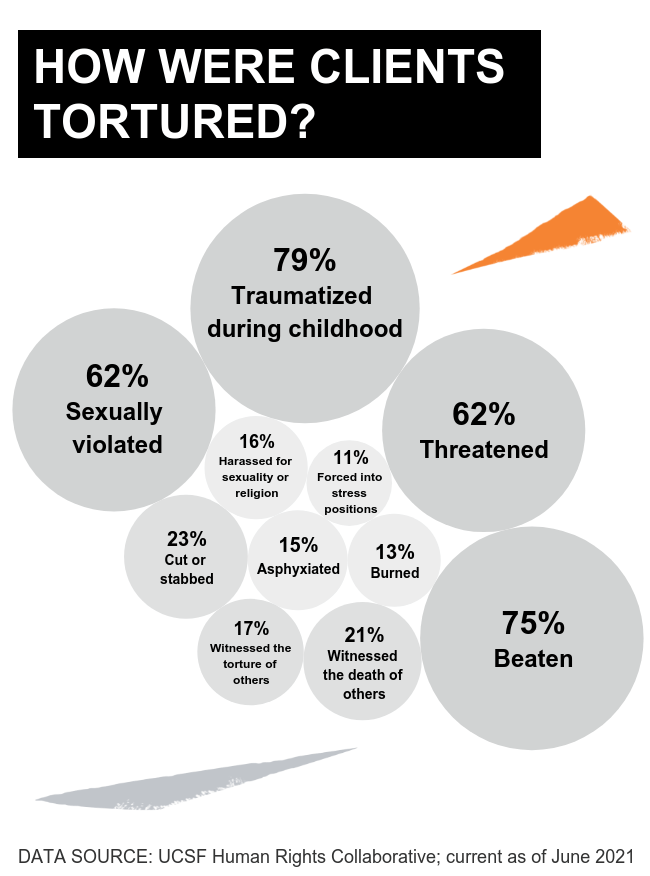

The photographs go on and on. Each one shows a scar, a signature of torture correlating to the chosen weapon. The scars belong to clients of UC San Francisco’s Human Rights Collaborative (HRC), a monthly student-run clinic that provides free forensic medical evaluations for people who have fled extreme violence or persecution in their home countries and are seeking asylum in the United States. Often, their scars are the only material evidence they have left of the agony they endured.

One chilly Saturday morning in August, medical students arrive at the clinic early to set up. They unpack boxes of snacks from Trader Joe’s – apples, sandwich wraps, potato chips, string cheese, granola bars, and cupcakes. On a table in the staff room, they lay out reference guides (“Electrical Injury and Torture,” “Sexual Dysfunction Following Torture,” “Sleep Deprivation,” “LGBTQI Patterns of Injuries,” and so forth) detailing the look, feel, and dimensions of scars and other vestiges of trauma. Next to the guides, they place soft rulers for measuring clients’ scars so they can precisely identify their cause.

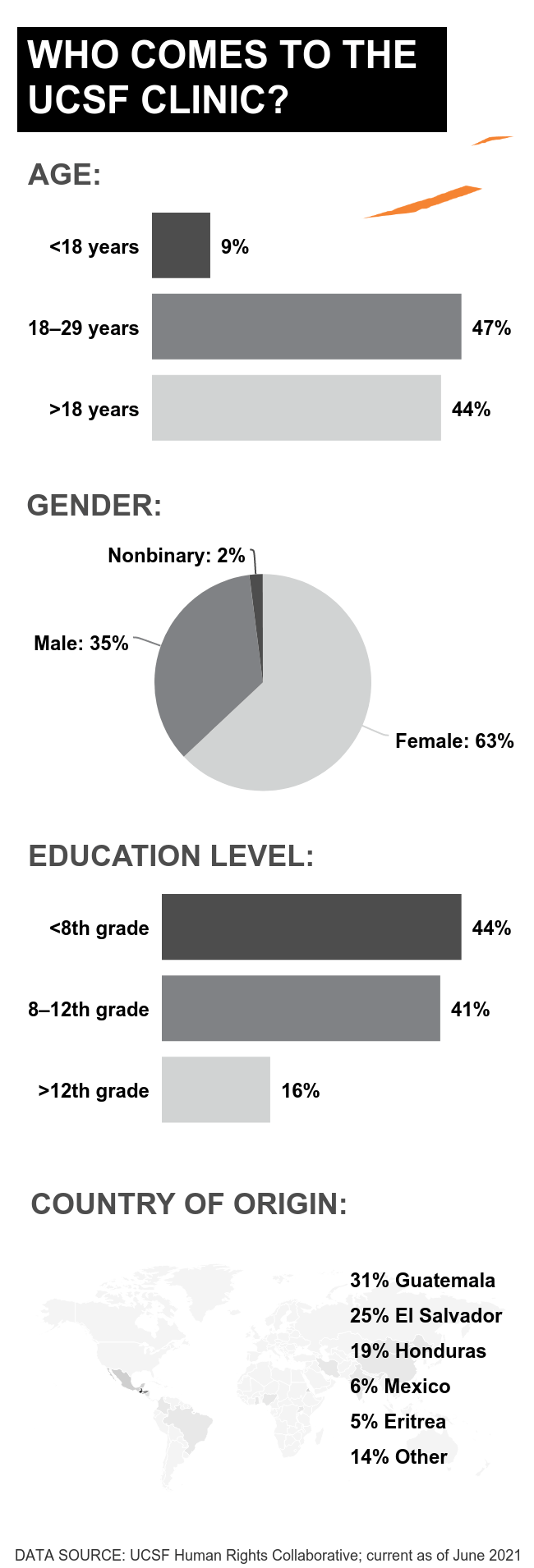

Today’s clients are three women from Central America who have come to the HRC on the advice of their pro bono lawyers. Like all the clinic’s clients, they are among the 1.3 million immigrants who have applied for U.S. asylum and are waiting – often for years – for their cases to be heard in court. These women are lucky to have lawyers at all. Only one-third of asylum-seekers do. With a lawyer, the chance of being granted asylum averages around 30% – up from 10% without one. And a good lawyer knows that a forensic evaluation raises the odds even more.

The students greet each woman at the clinic entrance, offer her tea and snacks, and usher her into an exam room. Each evaluation – performed by a UCSF clinician with help from a student apprentice and, when necessary, a medical interpreter – takes up to four hours. The evaluators listen to the client’s story and record in objective detail any physical or psychological signs of abuse. They then summarize their findings in an affidavit to support the client’s case in court.

The people we see have left their homes without photos, documents, or family, so there’s nothing and no one to verify their stories.”

Coleen Kivlahan, MD, MSPH

“The people we see have left their homes without photos, documents, or family, so there’s nothing and no one to verify their stories,” says Coleen Kivlahan, MD, MSPH, an international expert in torture evaluations and chair of the UCSF Health and Human Rights Initiative, which oversees the HRC. “The voice of the clinician can bear witness,” she says. “We look at every inch of their skin and interpret and reconstruct what happened. The body tells the story.” For many asylum-seekers, obtaining a medical affidavit “is a matter of life or death,” she points out. Even with legal representation, asylum-seekers are three times more likely to win their cases with such a document than without one; those who lose are often deported immediately. “They might literally be taken from the courtroom in handcuffs and put on a plane,” Kivlahan says.

Every year, more than 1 million migrants attempt to enter the U.S. in search of safety, and their numbers continue to increase due to shifting immigration policies, climate change, and humanitarian crises like those playing out in Afghanistan, Haiti, and elsewhere. The HRC is one of dozens of student-run clinics that have popped up at medical schools across the country over the past decade to help secure refuge for immigrants who fear returning home due to the threat of injury or death. To date, these clinics have together supplied thousands of pro bono medical affidavits to asylum-seekers, filling a gap left by private doctors, who aren’t typically trained to provide this service or who may charge high fees, Kivlahan says.

It’s no surprise that students are leading the way, she adds. Like the U.S. itself, medical schools are becoming increasingly diverse. More students than ever before come from immigrant families and communities of color, and they are demanding the skills and knowledge to care for these populations. “So many of our students have migration stories of their own,” Kivlahan says, “and their commitment to health justice and social justice is changing American medicine.”

Migration Stories

The HRC was founded in 2019 by three medical students: Francesco Sergi, Katrin Jaradeh, and Aaron Gallagher. Sergi’s mother and grandmother fled El Salvador during its bloody civil war in the 1980s and remade their lives in the U.S. Knowing their struggles, he says, “I have always been interested in trying to make the process of immigration easier.” Jaradeh emigrated from Syria with her family when she was 8 years old. “We feared being tortured because of our religion, so we did not feel it was safe for us to live there,” says Jaradeh, who was granted asylum just months before getting into medical school. Gallagher, who hails from Alaska, developed a passion for working with immigrants while teaching English to Somali refugees living in Anchorage. “They’ve endured incredible hardship, and yet they have a ton of positivity and resilience,” he says. “All they want is a better life.”

The three students decided to start the clinic after attending a lunchtime talk in which Kivlahan presented her work with asylum-seekers and other victims of torture. Kivlahan grew up “on the wrong side of the tracks,” as she puts it, in a small steel town in Ohio. Her father, whose family had immigrated from Ireland, worked as a roofer; her mother was a secretary. With six kids to feed, they couldn’t afford health coverage. To supplement the family’s meager diet, the children hunted frogs, and Kivlahan passed the time by dissecting the remains, which is how she fell in love with science. By second grade, she had made up her mind to become a doctor even though she had never seen one. After medical school, she did her residency and earned a master’s degree in public health at the University of Missouri and then took a job at a Missouri county clinic. It was there that her obsession with forensics began.

One day, a man arrived at the clinic carrying a bundle of old towels. Wrapped inside was the burned body of his 6-year-old stepson, barely alive. Kivlahan called 911, and while she waited for an ambulance, she noticed that the boy’s front teeth were broken and his forehead was dappled in yellow bruises. After he died, in a nearby hospital some hours later, she couldn’t get those marks out of her mind. “What struck me was how incredibly useless I was in being able to diagnose what turned out to be an extreme case of child abuse and homicide,” she says. “As physicians, we have very little training in those kinds of intentional injuries.”

Kivlahan devoted herself to learning everything she could about how to identify and give testimony about child abuse, sexual assault, and other forms of criminal violence. She observed hundreds of autopsies, studied forensic photography, shadowed detectives at crime scenes, and cajoled the county prosecutor into preparing her to be an expert witness. Soon, she was teaching the techniques of forensic evaluation to other care providers across the state. In the mid 2000s, she started volunteering with Physicians for Human Rights – offering evaluations to asylum-seekers and helping train doctors, nurses, lawyers, judges, and police officers in conflict zones how to document medical evidence of war crimes, including rape and the use of chemical weapons, and how to use that evidence to prosecute offenders. She has done this work in Guatemala, Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and most recently Syria, where people risk their lives collecting proof of the government’s atrocities that can be brought before international criminal courts.

Meanwhile, back in Missouri, Kivlahan continued to build a career in public health, eventually working her way up to director of the state’s Department of Health during the height of the AIDS crisis. After that, she bounced around the country – to Chicago, then Phoenix, then Washington, D.C., practicing family medicine and taking on various medical leadership roles – until, in 2016, she landed at UCSF as the executive medical director of primary care and a professor of family and community medicine. At that lunchtime talk in 2019, she recalls, she explained to a roomful of UCSF students how “a simple document from a doctor describing what happened” could save the life of an asylee. Soon afterward, Sergi, Jaradeh, and Gallagher got in touch with her. “We’ve heard there are clinics in other places that do this work,” they said. “Can we start one here?”

The three students spent the following months working with Kivlahan and Triveni DeFries, MD ’13, MPH, an assistant professor of medicine, to get the HRC up and running. The two professors promised to match however many hours the students invested. “We were putting in 25 to 30 hours a week, and they were right there with us,” Jaradeh says. To prepare medical students to work in the clinic, the team designed an elective course. “We thought we’d be lucky if we got five or 10 people who wanted to do it,” Kivlahan says. Instead, over the past three years, more than 100 students have taken the class. (“Compared with other electives, this is massive,” Gallagher notes.)

Trauma Stories

Mar C. was the HRC’s first client. Mar, who uses the gender pronouns they/them, was raised in Brazil as a boy. Because they wore pink and liked boys and science (rather than soccer), they were bullied by classmates. Starting at age 6, their parents tried to “cure” their homosexuality with bouts of electroshock therapy. They were harassed by gangs and beaten by police. Mar went to college hoping to find peace in studying chemistry, but the abuse continued; they decided their only chance at survival was to flee the country. They crossed into the U.S. over the Mexican border and eventually made their way to San Francisco. By the time Mar arrived at the HRC, at the age of 35, they were sick with AIDS and living in their car. After receiving asylum a year later, in 2020, they went back to school to train as a medical assistant and got an apartment and a job with the city health department, helping HIV patients navigate the health system. “My life changed entirely,” Mar says.

The clinicians and students who volunteer with the HRC have documented dozens of stories like Mar’s. Like the story of the drama professor from sub-Saharan Africa who was kidnapped by paramilitary forces and whipped, beaten, electrocuted, and sexually violated. Or the story of the young indigenous woman from Guatemala who had been trafficked for labor and sex since the age of 6, whose hands were marred by cigarette burns, and whose face was deformed from repeated blows. Or the story of the teenager from Eritrea who was conscripted into the military and disciplined cruelly and, when he protested, was shot and thrown into a cell with 35 other prisoners and no toilet. He escaped, ran barefoot through the desert to a refugee camp in Sudan, and then trekked to Kenya, where he met someone willing to smuggle him into the U.S. He was caught by border police and detained. “Our country put him in another prison after that journey,” Kivlahan says despairingly.

“These aren’t people who are coming here because they are trying to scam the system or get away with a crime,” Gallagher says. “These are people who have undergone very traumatic experiences with serious repercussions to their physical and mental health.” Entrusting their stories to strangers – immigration agents, lawyers, judges, even doctors – takes tremendous courage. “Having grown up undocumented here, I know our clients’ fear of deportation,” Jaradeh says. “The fear of going to the hospital, of asking for help – we were always scared that we would be sent back.”

To help clients feel safe, evaluators at the HRC practice trauma-informed care. They set clear expectations and let the client’s mental state guide the pace of the evaluation. As they listen and make notes, they look for signs of retraumatization. “I was with a client once who was sharing what life was like in their country,” Sergi says, “and they started wrapping their arms around their body, trying to make themselves smaller, closing in on themselves. They started crying and shaking their leg. I could tell they were dissociating. They were no longer in the room; they were somewhere else, reexperiencing something in their life.”

Such dissociative behaviors are the “scars” of psychological trauma. Nearly all the HRC’s clients show symptoms of major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. “They tell us they can’t sleep well, that they feel isolated or scared of being in public, that they can’t relate to friends or family anymore,” says DeFries, who co-directs the HRC with Kivlahan. These are important data points for an affidavit, but evaluators are careful not to overwhelm clients with questions. If they see that a client is dissociating, for example, they pause the evaluation. They might guide the client through a mindfulness exercise. “You ask them to become aware of the chair they are sitting in, their feet on the ground, their hands in their lap,” Sergi says. “You remind them that they are safe.” Another tactic is to hand the client a piece of paper and invite them to imagine their trauma playing out across the page, outside of themselves.

“These interviews require so much awareness and consciousness to be able to ground a patient who is going through a difficult moment,” says Zoë Onion, a third-year medical student who co-ran the HRC until 2020. She plans to bring the skills she developed at the clinic to her home state of Maine, where there is a large population of Somali refugees. “This experience has broadened my perspective on what I can do as a doctor,” she says, “and the impact I can have on the world.”

But the work of forensic medical evaluation can take a psychological toll itself. “You are exposed to the clients’ pain,” says Cristina Biasetto, MSW, the HRC’s mental health director and the clinical coordinator of the UCSF Trauma Recovery Center. “There is no way to escape being touched profoundly by their stories,” she says. “They become part of you.” Over the past year, Biasetto has run a support group for HRC volunteers. “We support one another in processing the experience,” she says. Part of that processing, she notes, is acknowledging that doing the job well requires deep empathy. “Being touched by this work is a sign that we are fully present for it.”

Human Stories

The end of an evaluation is always emotional. “Our patients say to me, ‘Dr. K, something broke inside of me,’” Kivlahan says. “What they mean is that something broke apart, broke open. Watching them leave the clinic with that feeling of freedom and peace is an extraordinary gift.”

Even in that one session, we can provide our clients with a sense that we see all of them – their humanness, trauma, resilience, and hope.”

“Even in that one session, we can provide our clients with a sense that we see all of them – their humanness, trauma, resilience, and hope,” says Suzanne Barakat, MD, a UCSF assistant professor of family and community medicine who joined the Health and Human Rights Initiative as its executive director in 2020. Born and raised as a Muslim in North Carolina, she has lost five family members to callous deaths: A brother and two in-laws in the U.S. were murdered by an Islamophobic neighbor, and an aunt and a cousin were assassinated in Turkey. “Because I have lived my entire life fighting just to be seen as human, I can understand why our clients feel like third-class citizens,” she says. “We want to empower them to achieve what they are capable of achieving, despite having to work through a broken system.”

In a recent episode of the podcast Hippie Docs 2.0, host Paul Linde, MD, asks Kivlahan if she feels she has been able to “make a dent” in the problem of human depravity. “You know, Paul,” she replies, “I’ve given up on that. Not that I’ve given up on a personal level, but I’ve given up on whatever ‘making a dent’ means. What I realize is that hatred and ignorance are everywhere. I think about the pyramid of hate, in which we begin with racial biases and ethnic biases and stereotypes; and we then move into a phase of speaking those things and acting on them; and then we move into policies around them; and then we move into things like genocide, which I’ve clearly seen.”

And yet, she continues, “I’m a perpetual optimist. I believe in human beings and I believe in our hearts, and when we’re touched and when we see [the pain and suffering of others], it changes us. The most hardened Congolese military guys, whom I’ve spent time with alone, have been completely impacted when they imagine their own daughters being sexually violated.”

The people who come to the HRC are our neighbors, Kivlahan notes. They are our housecleaners, our cooks, our dishwashers, our rideshare drivers, our students, our future doctors. Do we imagine them being sexually violated, stabbed, strangled, beaten, and burned? Do we imagine them fleeing their homes with only the clothes on their backs and the scars on their bodies? Do we imagine them learning English, finding new work, and raising their kids while being haunted by their past and the terror of being deported?

The work of the HRC, Kivlahan concludes, is to tell the stories many of us never could have imagined. “And we’re going to tell them in details that most of you don’t ever want to hear, and we’re going to show you photos that you don’t want to see,” she says. “But this is what happens.”