Aging Is Not Optional. Or Is It?

Geriatrician John Newman explains how science could intervene in the aging process.

Illustration: Abigail Goh

It’s not your imagination – the world is graying. In fact, by 2050, the global population age 65 and older is projected to nearly triple, to 1.5 billion. With this aging population, it will be more important than ever to reduce the burden of age-related disease. In the future, science will allow us to intervene in the aging process to make this a reality, according to geriatrician John Newman, MD, PhD. He explains what that means below.

What does an aging population mean for society?

It’s imperative to keep our older population healthy and independent as long as possible. As this population grows, we’ll need to provide help to increasing numbers of older people who are no longer independent. It will be a huge challenge for us as a society in the next 20 or 30 years.

What is aging? Why study it?

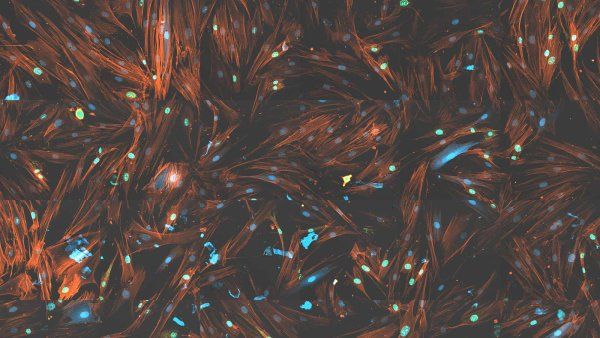

Aging is a biological and physiological process like any other. We can learn how it works – how cells and molecules create what we see as “aging” in a person. Aging can be beautiful, but it is also the number-one risk factor or driver of most of the medical problems that we treat in adults: cancer, diabetes, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular disease, strokes, and heart attacks. The crazy thing is we can manipulate the aging process. We can adjust it. We can treat it.

That sounds like science fiction.

None of this is science fiction anymore. It’s all science fact, right up to the part where people are doing clinical trials of drugs that treat complex health problems through targeting molecular aging mechanisms. In geroscience, we seek to understand the relationship between aging, disease, and quality of life. The promise of this field is that by intervening in the process of aging, we could slow, prevent, delay, or reduce the risk of all sorts of diseases – all at the same time.

John Newman, a resident alumnus, is an assistant professor in UCSF’s Division of Geriatrics and a researcher at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging. Photo: UC Regents

What interventions are being tested right now?

Metformin, a commonly used diabetes drug, also acts on mechanisms of aging. Clinical trials are looking at whether giving older people metformin will slow the rate of not only diabetes but also several other chronic diseases simultaneously. Also of interest are TOR inhibitors, which are drugs that can help cells better repair their proteins. In early clinical trials, it looks like treating older adults with TOR inhibitors can greatly reduce the rate of serious age-related respiratory infections like pneumonia and flu.

How will a visit to your primary care doctor look different in 2050?

You’ll have your aging mechanism risk factors checked, and you’ll probably have preventive treatments. For example, we’ll treat your senescent (old, inactive) cells or your autophagy (the process by which your body removes old, damaged proteins). If something is amiss in your risk factors, then we’ll make adjustments. It’ll just become part of regular preventive medicine.

When you are getting ready for surgery, we'll identify and treat your specific risks. Maybe your stem cells need a little help to make sure that your muscles recover well from the day of immobility. Maybe your brain needs a little protection to make sure that you don't get delirium from your surgery. I think by 2050, we'll be able to craft individualized precision interventions.

Will these interventions benefit everyone?

You can’t ignore disparities when you talk about aging and older adults. We need to figure out how to apply geroscience interventions through our health care system in a way that lets everyone access them. Wealth is one of the strongest predictors of life expectancy, overall health, overall function, and independence. There’s a biology to how wealth disparities affect aging and health. We don’t know what that is yet, but we aim to find out.

We also need more diversity in clinical trials, including a diversity of ages, to develop the evidence base on how to treat all people effectively. So many health problems mostly happen in older adults, but they are excluded from the clinical trials about those problems. This needs to change, for every aspect of health.

UCSF Magazine

Dive into the future of health in this special issue of UCSF Magazine.