It didn’t take Adil Daud, MD, long to realize that something unusual – unusually good – was happening to his patients. He was leading a clinical trial of an experimental drug against metastatic melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer. The trial was a phase I study, designed to examine the drug’s safety, not its effectiveness. But Daud couldn’t ignore its dramatic effect.

This was a last hope for his patients, since all other treatments had failed to slow their tumors. The drug, known by the unwieldy name pembrolizumab, had been designed to unleash the immune system against the cancer – a strategy with a history of only modest success, but one for which many oncologists have high hopes.

Adil Daud, MD. Photo: Cindy Chew

“We could see almost from the start that we had some really impressive responses,” says Daud, director of Melanoma Clinical Research at UCSF’s Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. Within a few weeks of the trial’s spring 2012 launch, more than 30 percent of participants’ tumors were shrinking – a threefold improvement over other immunotherapies for advanced melanoma. Oncologists at the clinical trial’s 11 other sites were seeing similar results.

“No other immunotherapy causes tumors to shrink in such a high percentage of patients, and these are lasting responses,” explains Daud, three years after the drug’s effect first became evident. The drug works by inhibiting a protein called PD-1, an approach he calls “a game-changer.”

Michael Agnew offers living proof of that fact. Now 69 and retired after a 30-year career with the California Highway Patrol, he was diagnosed with melanoma in 2005. Surgeons successfully removed a tumor from his nostril, and he had seven apparently cancer-free years. But the cancer had metastasized; in 2012, a chest X-ray revealed a mass in his lung.

Chemotherapy at UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento wasn’t effective. “It seemed to be chasing the cancer around,” Agnew says. A walnut-sized tumor in an adrenal gland narrowed his options. Then his Sacramento oncologist told him about the UCSF trial to block PD-1.

“I was in stage 4. I was the last or second-to-last to get in the program in that series,” he says. “This trial has been a godsend.... The tumor is now the size of a pea.” (Daud even suspects the remaining mass may be a residual scar rather than cancer.)

People with untreatable late-stage melanoma rarely live more than a few months. But about 80 percent of those who responded to pembrolizumab are still doing well, two years on. Some have even been deemed cancer-free.

With this drug, you are treating the immune system, not cancer,”

“With this drug, you are treating the immune system, not cancer,” explains Daud, “so drug resistance won’t develop. We think this type of drug is allowing the immune system to control cancer as if it were a chronic infection. Tumors might not disappear, but they can remain small and manageable.”

Furthermore, the drug is easy on Agnew’s body. “I don’t have the debilitating joint pain and other side effects I had with the other drug,” he says. “The biggest problem is fatigue the day after the infusion, but it’s not really serious.”

And Agnew isn’t alone. Daud and his fellow investigators have been impressed by how few patients have suffered the severe side effects of other immunotherapies, such as colitis and hepatitis. The most common secondary reactions to pembrolizumab have been fatigue, cough, joint aches, and rashes, though a small percentage of patients have experienced serious complications.

“Immunotherapy can be nontoxic, and its beneficial effects can potentially be long-term,” says Lawrence Fong, MD, associate professor and a leader in cancer immunotherapy at UCSF. “That’s transformative for cancer therapy.”

The startling results were so promising – and melanoma patients’ other options so limited – that in September 2014, the FDA gave accelerated approval for using pembrolizumab against advanced melanoma that hasn’t responded to other treatments. Approval is rare for drugs not yet tested in large phase II and III trials. Pembrolizumab is now being marketed by its manufacturer, Merck, under the more user-friendly name Keytruda.

Patients in the trial, which is still ongoing, receive half-hour infusions of Keytruda every two weeks at Diller Cancer Center. Agnew and his wife, Carol, are able to drive down from Sacramento and back the same day. The current plan is to continue his treatments for six more months.

He’s one of the lucky ones, but he’s not a rarity. “I feel very, very fortunate for where I am now,” he says. “I go on day motorcycle rides with my friends again. We have an RV, and Carol and I take trips for days at a time. I garden. The things that retired people do. I feel great.”

The trial’s outcome has helped spawn dozens more trials pitting pembrolizumab against other types of cancer. It is now, often in combination with other drugs, shrinking advanced cancers of the lungs, bladder, and kidneys, as well as certain types of breast cancer.

Using it with other drugs appears to have a stimulatory effect on the immune response, Fong says, boosting its ability to kill cancer cells. Daud thinks combination treatments might ramp the success rate up to 60 percent.

Deploying the Army

T cells, the aggressive soldiers of the immune system, attack infected cells in the body and demobilize invading pathogens. To prevent indiscriminant killing of normal cells, the immune system employs molecular “brakes” to restrain the army in the presence of “self” cells and tissues. (A failure to apply these brakes is what triggers auto-immune diseases like multiple sclerosis.)

But cancer is not a foreign invader. Tumors are mutated versions of the body’s own cells. They don’t “look” abnormal to the immune system, so the brakes go on. Unimpeded, the cancer spreads.

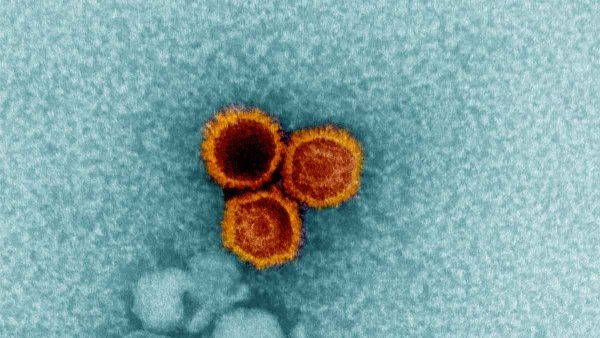

One of T cells’ molecular brakes is controlled by the PD-1 protein. If it links to another tumor-cell protein, PD-1 turns off the T cells. But Keytruda blocks the two proteins from connecting – essentially cutting the brake line and freeing the T cells to attack the tumor.

Keytruda is the second “brake-releasing” drug approved against melanoma. The first – Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Yervoy, which blocks a different immunological protein – was approved in 2011. It has succeeded in a smaller percentage of patients and causes more serious side effects, but, like Keytruda, has achieved impressive, lasting tumor suppression.

Not surprisingly, early word of Keytruda’s tumor-shrinking powers in the clinical trials has led to an explosion of interest among drugmakers. Three other companies are now running trials of different drugs that inhibit PD-1. One was approved in December. And Genentech is conducting trials targeting PD-1’s partner protein.

More than 30 other immune proteins besides PD-1 may help turn T cells on or off, Fong says. He estimates that at least 10 are already in trials. And, he adds, “every six months I see new targets that companies are going after. It just gets bigger and bigger.”

He, Daud, and others are also studying why only certain patients respond to such treatments. Fong’s lab is trying to understand at a molecular level what T cells “see” when the immunological brakes are released. And Daud recently found that 30 percent of participants, all of them among the cohort that did not respond well in the trial, lack a key protein involved in blocking PD-1. Such patients may benefit from emerging drugs that free the molecular brakes in other ways.

Three years after he first observed the effect of targeting PD-1, Daud has high expectations for unloosing the body’s T cells against cancer. “I’m predicting that in 10 years, every cancer treatment regimen will have some immunotherapy component – whether aiming at PD-1 or another immune protein target. It will be part of the toolkit.”