Probiotics: Health Hack or Hype?

Marketers say microorganisms can fix a lot of what ails us. Do scientists agree?

Illustration: Farah Hamade

If there’s one thing about probiotics that’s certain, it’s this: they’re popular. More than 4 million Americans regularly use probiotics, which contain live bacteria or other microorganisms and claim to help with ailments ranging from diarrhea to depression. But should science-minded consumers believe the hype?

We turned to UCSF researchers to help us better understand these products and the human microbiome they aim to influence.

Myth #1

All probiotics are created equal. They contain similar bacteria that will benefit anybody’s microbiome.

If only!

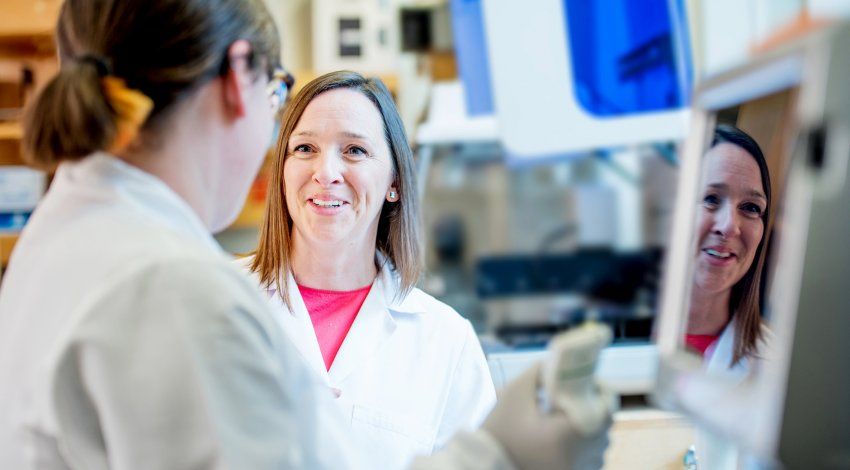

The microbiome is incredibly complex, according to Susan Lynch, PhD, director of UCSF’s Benioff Center for Microbiome Medicine.

“It senses and responds to everything from the pharmaceuticals we consume to dietary influences to environmental pollutants,” Lynch says. “Microbes also interact with each other, competing for nutritional resources and real estate. There are a lot of variables in the equation.”

With so many factors at play, it’s fair to assume that your microbiome is not identical to anyone else’s – and your reactions to a particular probiotic will be unique, too. The colonies of microorganisms already residing in your body determine whether the new bacteria you’re introducing will have any effect or even get a chance to stick around.

The many different types and combinations of bacteria for sale further complicate that equation. Some strains have been studied in a few clinical trials. Others have zero research behind them.

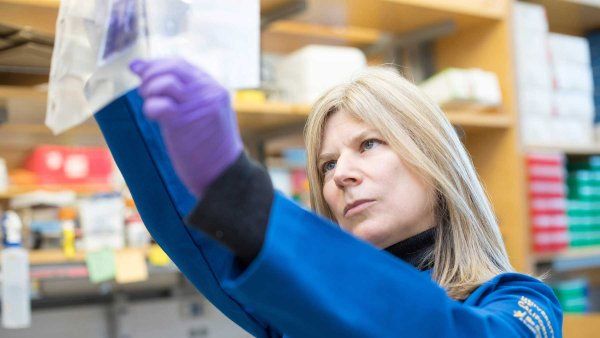

“Many people are not aware that regulation of probiotics is relatively minimal,” says Peter Turnbaugh, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology. “There’s no guarantee that the bacteria listed on the label are actually in the product or that those are the only microbes that have been added.”

Diet Changes the Gut Microbiome

Learn about Turnbaugh’s research on raw food and the ketogenic diet.

Myth #2

Bacteria are only beneficial in your gut, so it makes sense that most probiotics are packaged in pills.

Not so much.

Humans have distinct microbiomes in different parts of our bodies, from our mouths to our feet. The gut is just the most studied.

For example, an imbalance in the vaginal microbiome can lead to bacterial vaginosis (BV), a common condition that increases a woman’s risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections (including HIV) and of giving birth prematurely. BV can be treated with an antibiotic, but many women are reinfected within weeks.

That’s why Craig Cohen, MD, MPH, a professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences, recently led a clinical trial of LACTIN-V, a powder containing a bacterium found in healthy vaginas. Just 30% of women who used LACTIN-V after antibiotic treatment had a recurrence of BV within three months, compared to 45% of women who received the antibiotic and a placebo. Cohen hopes that LACTIN-V might one day help women with BV establish a stable microbiome that lasts for years.

Until then, Cohen says women interested in probiotics could experiment with existing, albeit unproven, products designed for use in the vagina. But swallowing a probiotic capsule? He doesn’t see the point.

“Most of the products on the market contain bacteria that are not naturally found in the vagina,” Cohen says. “So it’s not the right bacteria, and you’re not getting bacteria at the right place.”

When it comes to the gut microbiome, swallowed supplements make more sense. But they might not be the best way to create lasting changes – and those changes might have effects that reach far beyond the gastrointestinal tract.

“Small molecules produced by the gut microbiome enter the circulation, and they influence the behavior and the function of cells at remote sites,” says Lynch.

For example, Lynch’s lab discovered a connection between a newborn’s gut microbiome and their risk of suffering from allergies and asthma. And Sergio Baranzini, PhD, UCSF’s Heidrich Professor of Neurology, led a study that found gut immune cells travel to patients’ brains during multiple sclerosis flare-ups and seem to help control symptoms.

Scientists are also examining whether neurological disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, can be treated by modifying gut bacteria. In those studies, treatment typically consists of a fecal transplant, drawing on the full spectrum of gut microbes donated by healthy volunteers. Fecal transplant is also a well-established treatment for patients who cannot beat Clostridium difficile – a deadly, colon-dwelling superbug – with antibiotics.

Myth #3

Introducing live bacteria to your body is the only way to reap health benefits from your microbiome.

Not necessarily.

According to Turnbaugh, we still don’t understand all the mechanisms involved in the human microbiome, let alone the best ways to ultimately manipulate individual microbiomes.

Take yogurt, for example. Some nutritionists recommend yogurt because it supposedly contains beneficial bacteria. But live bacteria, while crucial to making yogurt, don’t necessarily survive for long. By the time you’re spooning it into your mouth, most of them might be dead. Does that mean the yogurt doesn’t benefit your gut?

Turnbaugh argues that we don’t know yet.

“We’re starting to understand little pieces of the puzzle, but it’s probably going to be a while until we can put them all together,” he says. “I’m not convinced that focusing on viable organisms is necessary. If your yogurt contains a ton of a bioactive compound produced by the bacteria, you might not even need the microbes to be alive.”

That’s the theory behind postbiotics, an emerging research focus. Scientists also carefully consider prebiotics, which are anything that bacteria consume.

So when you eat inulin, a prebiotic fiber found in some fruits and vegetables and added to processed food, like candy bars, live microbes in your gut thrive on it. As they break down the inulin, they spit out a waste product, butyrate. Butyrate – a postbiotic – then serves your body, helping the cells that line the gut function. Without butyrate, intestines can become too permeable, allowing not only nutrients and water to pass through, but also toxins and other food waste that belong in a toilet, not your bloodstream.

“It’s one of the most interesting things about the microbiome,” Turnbaugh says. “We really need the gut microbiome to develop properly and avoid disease later in life. But there are many points in the pathway that you can potentially tweak. Probiotics are just one way to get at it.”

The complexity of the microbiome makes it an exciting field of study. That complexity also means scientists have much more work to do before they can, say, interpret individual microbiomes and prescribe proven solutions.

“There’s a lot of impatience with this field, but in a little over a decade since its inception, we’ve learned a tremendous amount,” Lynch says. She adds that the Benioff Center for Microbiome Medicine was founded to foster collaboration and fund studies, speeding up innovation.

“Microbiome research, by definition, is interdisciplinary,” she says. “You cannot study the microbiome by itself. It needs to be studied in the context of immune response, clinical outcomes, etc. The center is bringing those interdisciplinary investigators together.”

In the meantime, for those who want to learn about the research behind a probiotic product (or lack thereof), Turnbaugh recommends usprobioticguide.com.

“Be skeptical, as with anything that’s marketed,” he says. “But there’s nothing wrong with just trying some out to see if they work for you.”