Ask Aenor Sawyer, MD, about the promise of digital health, and she’ll tell you about a pitch for a health-related app that she critiqued not long ago. The app purported to improve spinal health – something that Sawyer, an orthopedist and a former physical therapist, knows a thing or two about.

“I raised my hand and asked, ‘Does it work?’” recalls Sawyer, who is an assistant clinical professor at UC San Francisco. “The developer’s answer was, ‘It has 1,500 downloads and is fully funded.’”

His metrics for success were understandably different from a clinician’s, but his answer indicated to Sawyer an obvious need to have experts from multiple disciplines – including health care and technology – at the table when designing digital innovations. Digital health inventions can come in the form of software or devices that sense, collect, integrate, and analyze health data. “Some of the earliest digital health apps were developed with minimal clinical input and had early-adopter appeal, but little or no demonstrated effectiveness,” says Sawyer, who is also the associate director of strategic relations at the new UCSF Center for Digital Health Innovation (CDHI). “Thankfully, that is changing as we create partnerships across sectors.”

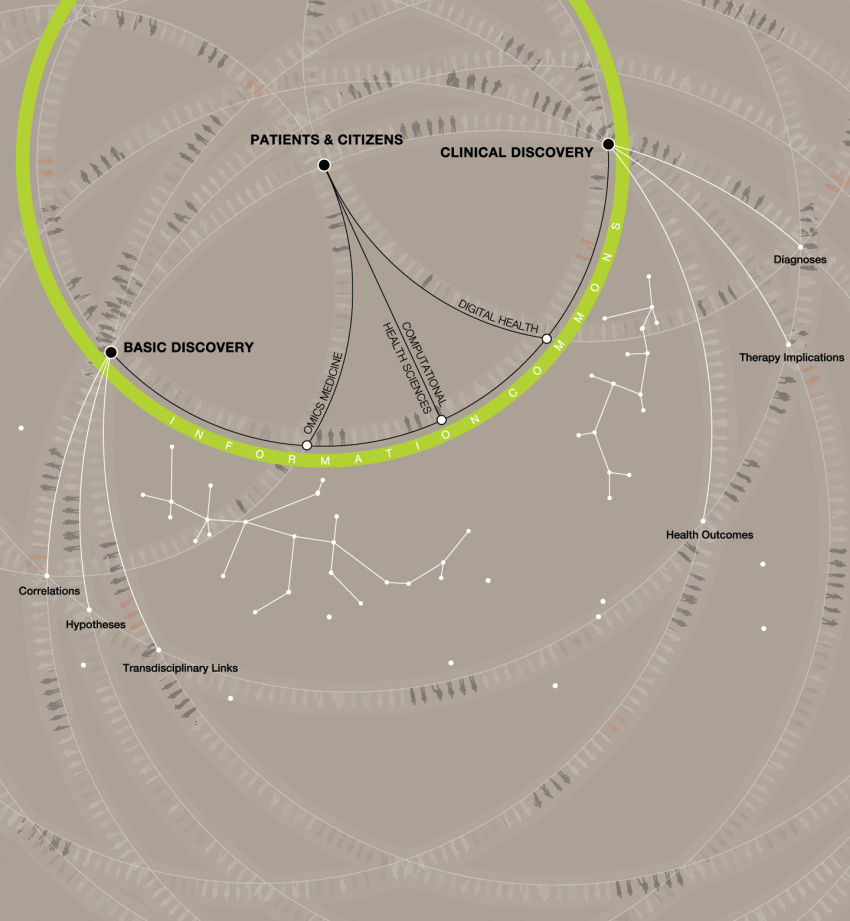

Led by UCSF’s associate vice chancellor for informatics, Michael Blum, MD, the CDHI is vital to the success of the institution’s precision medicine initiatives. The CDHI not only shepherds the development of digital health innovations created at UCSF, but also validates the effectiveness of digital health devices developed both within and without the institution. A key focus of CDHI is facilitating the flow of data from disparate sources into the clinical care process so that optimal treatment can be offered to each individual patient.

UCSF faculty, staff, and students who are developing new digital health systems and devices benefit from the vantage point of being integral to the processes and practices they seek to enhance. “I call them frontline innovators because they can target problems that people from the outside may not appreciate,” Sawyer points out. “They also bring in the evaluation component to ensure that the technologies being developed are not only used, but are effective.”

I call [UCSF faculty, staff, and students] frontline innovators because they can target problems that people from the outside may not appreciate.”

“The CDHI’s partnerships help UCSF innovators cross the arc from ‘idea to impact.’ Ongoing efforts are under way to build these valuable industry-academic relationships. Our diverse partners span technology, design, business, and even policy,” says Sawyer. “They advise our innovators on every aspect of making a commercially viable product.”

The CDHI has begun to serve as a coordinating center for other UCSF organizations – such as the Office of Innovation, Technology, and Alliances; Information Technology Services; and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute’s Catalyst program – all of which help digital health innovators to develop, validate, and scale their work beyond the University. “Catalyst alone has more than 100 industry and academic leaders in fields such as engineering, design, legal, and finance who serve as advisers to help innovations evolve and move out of UCSF,” she says.

Aenor Sawyer, right, discusses the importance of new technology being not only innovative but practical and effective. Photo: Steve Babuljak

The CDHI has a broad portfolio of pipeline projects, of which Trinity is but one example. Developed by Sawyer and Pierre Theodore, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon, Trinity is a web-based tool that enables a multidisciplinary team of physicians to confer virtually about complex cases. In cancer care, such teams, known as tumor boards, are made up of 20 or more physicians who leave their clinical duties to meet for an hour or two each week to review their patients’ clinical, radiology, laboratory, and pathology data. Tumor boards engage in crucial discussions about the most challenging cases, but it may take four weeks to schedule a face-to-face meeting and another two weeks to initiate the resulting treatment plan. With Trinity, team members can access all the relevant data online and comment and confer with colleagues virtually – at their own convenience, in a way that safeguards patient privacy – and then treatment plans can be implemented in 48 hours.

“Technology enables us to deliver better care at lower cost,” says Sawyer. “We have also demonstrated the ability to gain input from specialists outside UCSF – and even the country – on unusual cases.” Trinity is fully operational at UCSF. Plans for building it into a commercialized product are under way.

Photo: Steve Babuljak

Other technologies in development at the CDHI use mobile devices and social media to collect dizzying amounts of health information from people, as they go about their lives, and make use of it to serve individual patients. Social analytics, which measure, analyze, and interpret our social interactions and patterns, are also a key part of the data used in digital health innovations. “We now have the ability to peer beyond our clinical settings and integrate real-life data with the physiologic data collected by the health care system to better understand their contributions to health and disease,” says Sawyer. “The challenge will be managing and analyzing the data in a way that is clinically useful.”

Fundamental to that challenge will be integrating systems and data into compatible languages so that the new technologies work together, while maintaining patients’ privacy. The CDHI will also guide developers in an array of evolving legal and regulatory matters, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), a federal law that safeguards patient privacy.

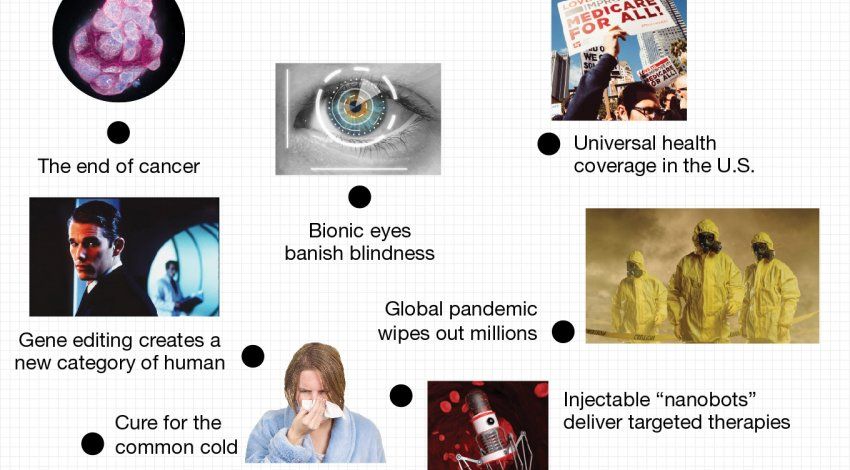

“We are living in an exceedingly complex world involving technologies that will allow associations not previously possible,” says Sawyer. “With digital health as the great communicator, we will see the integration of genomic, physiologic, behavioral, social, and environmental data to achieve not just descriptive, but ultimately predictive and perhaps prescriptive information for patients and providers.” As that evolution takes place, the CDHI will be poised to ensure that all these new sensors, apps, and databases interface efficiently with the clinical care process, in order to realize precision medicine’s promise of timely, individualized, data-driven care.