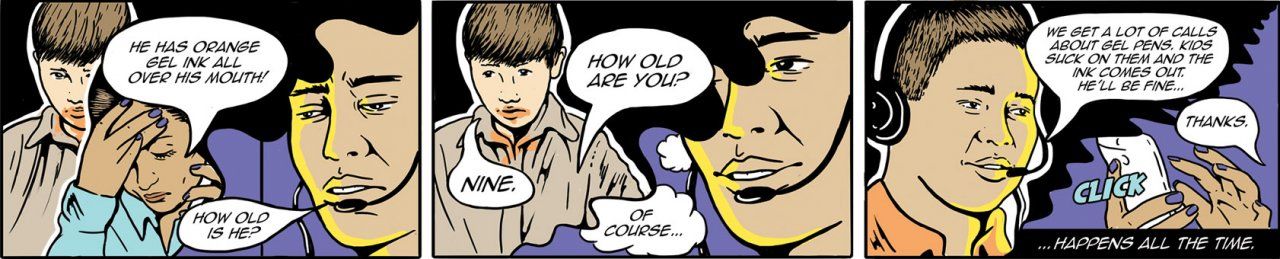

The phone rings. Ben Tsutaoka picks up. “Poison Center,” he says. The caller is a teacher. She’s with a student. He was chewing on a gel pen, and it exploded…

Ben Tsutaoka, PharmD, is a UC San Francisco associate clinical professor of pharmacy. He’s worked in the San Francisco division of the California Poison Control System (CPCS) for 19 years, answering phones. If you call the toll-free Poison Help hotline, at any time, on any day, from anywhere in California, you’ll reach CPCS. (The system also has divisions in Sacramento, San Diego, and Fresno/Madera, all administered by the UCSF School of Pharmacy.) Maybe you’ve talked to Tsutaoka. He and the other four dozen or so CPCS poison experts field about 700 calls a day. One call every couple of minutes, on average.

Most callers are members of the public (parents or siblings or nannies or teachers), but almost a third are medical personnel (nurses or doctors or emergency responders). The callers’ predicaments run the gamut: They got bug spray in their eyes. Their sister took too much Prozac. Their baby swallowed the metal ball from a toy maze. Their patient appears to be in the throes of an opioid overdose.

Some people call because they’re genuinely scared. Others call just for reassurance. When a clinician calls, it’s usually to get an expert opinion on an unusual or difficult case. But really, everyone calls because they – or more often someone they’re with – has ingested, inhaled, or otherwise come into contact with a suspect substance, and they urgently need to know: How bad is it? What should they do?

All day long, the calls toggle between mundanities and near-disasters – with lots of people worrying about matters that really aren’t problems, mixed in with a few genuine emergencies, some of which may herald the start of a poison epidemic. To listen in on these calls is to witness a strange reflection of the world – one in which the things we eat and drink and use and depend on every day suddenly seem out to kill us. It’s a stark reminder of the dangers of modern life, including the rise of opioids, the emergence of e-cigarettes and synthetic marijuana, and the candy-like appearance of single-use detergent pods.

But the CPCS also represents a cause for hope: evidence that our fears are often exaggerated, that despite life’s hazards, we are safer and more resilient than we think.

The art and science of answering phones

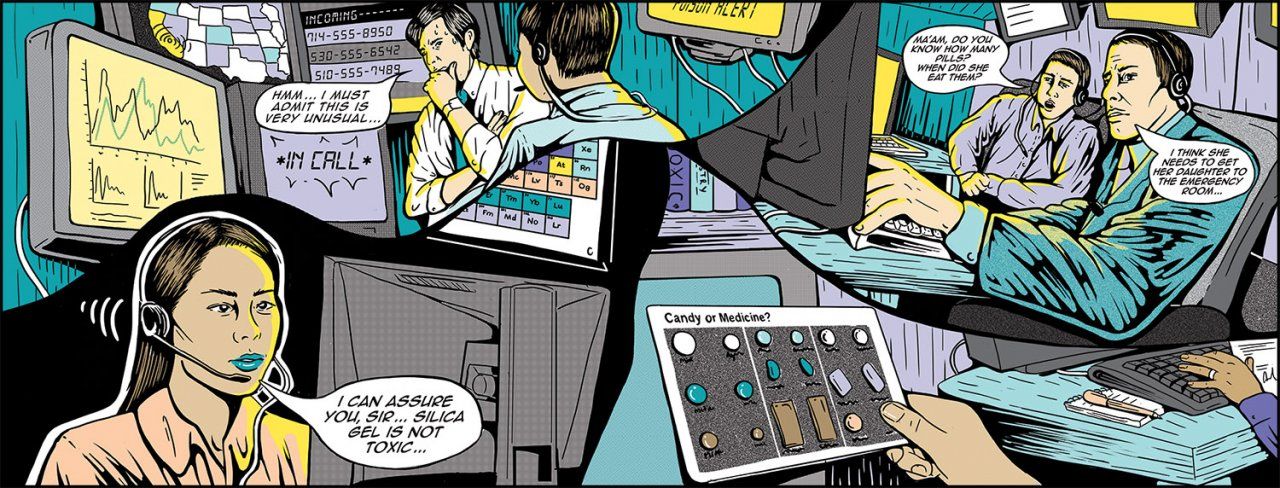

The phone rings again. Sandra Agustin, PharmD, answers. She’s a recent hire. She sits catty-corner from Tsutaoka in the San Francisco division – a well-worn room ringed with desks, located a couple of blocks from Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital (ZSFG). Along one wall is a shelfful of textbooks: Pediatric Dosage Handbook, Poisonous Plants of California, and Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. On a table sits a display case of medicines paired with candy look-alikes. “Labels tell which is which,” it warns, “but most kids can’t read between ages 1 and 6.”

A man is on the line. He’s breathing heavily. He was out running errands when his wife called him, frantic. She’d just stepped out of the shower and saw that their 3-year-old son had eaten some thyroid pills. Could be as many as 20, the man says.

Agustin asks what brand the pills are, how many micrograms, and when the boy ate them. The man doesn’t know, doesn’t know, doesn’t know. He calls his wife and patches her in. Levothyroxine, 175 micrograms, 10 minutes ago. Agustin taps on her calculator, using the kid’s estimated weight to determine the toxicity of the dose. Likely poisonous, she concludes. “It’s a good idea to take him to the emergency department,” she tells the parents.

This scenario is many callers’ worst nightmare. Most of the time, though, callers are relieved to learn they have nothing – or very little – to worry about. “People are so grateful when we can tell them that,” says Rais Vohra, MD, the medical director for CPCS’s Fresno/Madera division and a professor of clinical pharmacy and emergency medicine at UCSF Fresno. In addition to assuaging callers’ fears, CPCS estimates it saves Californians upward of $90 million per year in unnecessary medical costs – about seven times its annual budget. A call, after all, is a lot cheaper than a trip to the emergency room.

But, of course, emergencies do happen.

Another call. A woman, panting with exertion.

She’s out on the street, hurrying to the house of her 15-year-old sister. The teen takes Prozac for depression, the woman says, usually two pills a day. She’d just eaten five at once. (Or maybe more. CPCS toxicologists know that people who are suicidal sometimes lie about how many pills they’ve taken.) “Was this on purpose?” Agustin asks.

“I don’t know, you tell me,” the sister says. Like, would someone do that by accident? It’s as if she doesn’t want to say it out loud – that maybe her sister was trying to kill herself.”

These calls – in which the person on the line is breathing hard, in which a life all of a sudden has taken a horrible turn – are hard to listen to. Your heart quickens, your palms sweat. Just listening. Can you imagine, you think, can you even imagine?

But after Agustin gets off the phone – after she’s sent the sisters off to the hospital for help – she’s cool, collected, not sweaty at all. Part of the job, she says.

The job, as one might imagine, requires a deep understanding of human physiology plus an encyclopedic knowledge of substances both dangerous and innocuous. Poison experts must be able to recall and synthesize this information quickly and relay it in a way a caller can understand. “It’s a steep learning curve,” says Justin Lewis, PharmD ’09, the managing director of CPCS’s Sacramento division and a UCSF associate clinical professor of pharmacy. “Poisoning isn’t something they teach to a significant extent in pharmacy school.”

Just as important, he says, you must be able to convey confidence and empathy and stay calm under pressure. Getting your message across can take some persistence. About half of the calls to CPCS concern children under age 5, and although their exposures are often benign or only mildly toxic, it can be hard to convince a panicked parent that the things they think are harmful actually aren’t.

Take, for instance, silica gel packets. These little moisture-absorbing pouches are one of the most common causes of calls to CPCS. They come tucked in countless products, from electronics to dried seaweed. They’re often labeled “DO NOT EAT.” But that’s because silica isn’t food, Tsutaoka explains, not because it’s toxic. Decades ago, when he was studying to become a pharmacist, he was surprised to learn this. He went home and ate some packets, just to be sure. “They’re crunchy,” he recalls. But nothing happened. “So then I was a believer.”

The trickiest calls tend to come from health care professionals. “The calls that stick out are the ones where the patient is actively dying,” says Serena Huntington, PharmD ’11, the managing director of CPCS’s Fresno/Madera division and a UCSF assistant clinical professor of pharmacy. “The doctor is on the phone with you, and they’re wanting to know what kinds of quick antidotes they can give.”

The phone rings yet again. A nurse is calling from an emergency room. Tsutaoka takes it. It’s about a 19-month-old boy, the nurse says. He got into a bottle of chemotherapy pills and ate an unknown quantity. How does CPCS advise treating him?

Tsutaoka types the name of the drug, Xeloda, into an online database of toxicological information and scans the articles. “Interesting,” he says. “Hmm.” He tells the nurse he’ll call her back. He’s never had a case involving this drug before, he says. “It’s something kids don’t usually get into.”

He huddles with the division’s managing director and two on-duty physicians who are here to help in situations like this. They believe the exposure isn’t immediately life-threatening, but it could become so as the medicine works its way through the boy’s system. Best to play it safe and give the boy Vistogard, an antidote. One of the physicians says he’ll follow up with the nurse so that Tsutaoka can get back to the phones.

The dose makes the poison

Another call. A mom. Her kid had put his finger on the counter where she had cut up some raw chicken, and before she could stop him, he had stuck his finger in his mouth. She doesn’t know what to do.

“I know it’s horribly dangerous,” she says.

Not really, Tsutaoka tells her, in the very kindest way. It’s actually pretty rare to get infected with E. coli or Salmonella, he says. Watch the kid closely, and if he gets diarrhea, give him some Pedialyte.

Agustin is on the phone with another mom. Her daughter was spraying her keyboard with cleaning solution, and some of the spray went in her glass of water. She didn’t notice until she drank some of it. “She’s hysterical,” the mom says. She sounds embarrassed. Her daughter is a college student. “I think it’s more about stress.”

Agustin is understanding. If the daughter had gotten a full glug of the cleaner, that might be a problem, she reasons out loud. But half a misting, diluted in a glass of water? “I don’t expect her to have any symptoms,” she tells the mom.

It’s not always easy to figure out what’s poisonous and what’s not. Look up “poison” in Merriam-Webster and you’ll learn it’s “a substance that through its chemical action usually kills, injures, or impairs an organism.” This definition, though, is so broad as to be nearly worthless. “What is there that is not poison?” wrote the Swiss physician Paracelsus in the 16th century. “All things are poison and nothing is without poison. Solely the dose determines that a thing is not poison.” In other words, all substances are potential poisons – aspirin, glass cleaner, even table salt – but we usually encounter them in benign amounts. Pop an aspirin. Wash a window. Sprinkle some salt. At some level, there’s a toxic dose, sure, but where exactly is the line between safety and danger?

For most of human history, poisons came primarily from the natural world – plants, fungi, minerals, animals. Common toxic exposures therefore remained more or less the same for millennia. Among them were arsenic, cyanide, mercury, opium, lead, mushrooms, and alcohol. Starting in the early 20th century, however, homes across the developed world filled with new medicines, cleaners, pesticides, and other synthetic products – fruits of the burgeoning science of chemistry.

By 1955 in the U.S., 250,000 different trade-named substances flooded the market. Accidental child poisonings had become a crisis, causing more than 400 deaths a year. With little knowledge of what the new products contained and how they affected the body, clinicians found it difficult to both treat exposures and warn the public about them.

It was against this landscape that poison centers emerged. A pharmacist named Louis Gdalman established the first one at St. Luke’s Hospital in Chicago in the 1930s. Illinois pharmacists Anthony and Natalie Burda recount its history in the journal Veterinary and Human Toxicology. Initially, they report, Gdalman just advised the hospital’s own staff. But soon he was taking calls from across the city. “Louis was called day and night,” his wife recalled to the Burdas. “He never refused a call.” He recorded what he learned about poisons, doses, and antidotes on small cards, thus creating the country’s first (albeit crude) toxicological database.

Gdalman’s model spread quickly. By the late 1970s, more than 600 poison centers dotted the U.S. They helped initiate public awareness campaigns, educating parents about poison hazards and advocating for child-resistant packaging. As a result, even as the population boomed, child poisoning deaths dropped – to fewer than 50 a year today.

However, isolation and disorganization plagued the early centers. Each had its own phone number and methods of operation – some more sophisticated than others. “A lot of them were just little pieces of hospitals or pharmacies,” says Stuart Heard, PharmD ’72, CPCS’s executive director and a UCSF clinical professor of pharmacy. Often, poison center employees had little or no expertise in toxicology, he adds.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers, established in 1958, pushed for consolidation and standardization. In California, the number of poison centers shrank from more than a dozen in 1980 to just four in 1997, when the California Emergency Medical Services Authority united them under the CPCS moniker. At the time, the four centers – housed at ZSFG, at the UC Davis and UC San Diego medical centers, and at Valley Children’s Hospital in Madera – had different cultures and procedures, says Lee Cantrell, PharmD, the managing director of CPCS’s San Diego division and a clinical professor of pharmacy at UCSF and UCSD. “Each site was its own kingdom, more or less.”

After winning a contract bid, the UCSF School of Pharmacy took over administration of the CPCS, merging the four divisions into one statewide service. While some regional flavor remains (San Diego has particular expertise in snakebites, for instance, and Northern California in mushrooms), they now work “like one big call center but spread out,” Heard says. Today, no matter where you are in California, you can call the same number and know you are getting the same quality of service.

Exposing new threats

All morning at the San Francisco division, the room hums as students and fellows follow up with people who had called earlier, learning how things turned out. Education is a large part of CPCS’s mission, Heard says. UC pharmacy and medical students can choose to do a clerkship at a CPCS division as one of their clinical rotations. Three of the four divisions also serve as training sites for post-residency fellowship programs in medical toxicology – the science and practice of diagnosing, managing, and preventing poisonings.

Now it’s mid-afternoon. The doldrums. Calls slow to a trickle. The volume will pick up again around 4 p.m., when people start getting home from work and school.

The tide of calls ebbs and flows with the rhythms of daily life but usually holds steady throughout the year. On occasion, though, a tsunami strikes.

Sometimes the surge merely reflects a new societal fear. In September 2001, after letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to several politicians and media outlets, killing five people and infecting 17 others, calls poured into CPCS. “The whole country just went crazy thinking that anthrax was everywhere,” Heard says. “Our role was to reassure them that was highly unlikely – that the white powder they found in their kitchen was just something they spilled.”

A similar wave of calls followed the literal tsunami that, in 2011, destroyed a nuclear power plant in Fukushima, Japan. Many Californians worried that radioactive debris would make its way across the Pacific to the state’s coast. Dozens of people called CPCS asking where to find potassium iodide, an over-the-counter compound that can protect the thyroid from radiation damage. Other people called because they had taken too much potassium iodide; in an attempt to protect themselves from poison, they’d poisoned themselves.

Other times, an influx of calls signals a new poison hazard, allowing CPCS to quickly identify the threat and alert the public. A few years back, for example, Raymond Ho, PharmD ’04, the San Francisco division’s managing director and a UCSF associate clinical professor of pharmacy, was working the phones when he started getting suspiciously similar calls from several hospitals around the city. Kids were arriving at emergency rooms with glazed eyes, lethargic and vomiting. Nobody knew what was happening. But some of the clinicians had a suspicion, which CPCS toxicologists confirmed: The kids were stoned. CPCS briefed the city’s public health department, which investigated. It turned out the kids had all been at a quinceañera party, and somebody had set out a tray of cannabis-infused gummies.

One of the largest and scariest poison outbreaks is still ongoing. It started in 2015. That fall, a man showed up at ZSFG looking like he’d overdosed. His pupils were tiny, he was having difficulty breathing, and he appeared to be heavily sedated. He insisted he’d only taken a Xanax, an antianxiety drug. Toxicologists at CPCS’s San Francisco division had the man’s pills tested and found they were laced with a high dose of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 100 times stronger than morphine. They immediately notified public health officials. “We suspected we were just seeing the tip of the iceberg,” says Craig Smollin, MD, the division’s medical director and a UCSF professor of emergency medicine.

Sure enough, hospitals across the Bay Area and Central Valley began calling CPCS regarding similar cases. People were buying, either on the street or online, what looked like common recreational drugs or pharmaceuticals – Xanax, OxyContin, methamphetamine – but were actually much more potent counterfeits. “We were able to surveil the outbreak and team up with our colleagues in the health department to get the word out to the community,” Smollin says. While synthetic opioids are still a growing problem, those early warnings likely saved lives, he says. “It makes me feel we’re doing something really important.”

Recently, CPCS has also begun taking a more active role in helping to combat opioid use disorder, which causes tens of thousands of deaths per year nationwide. “We said, ‘How can we leverage our expertise to help mitigate this epidemic?’” says Kathy Vo, MD, an assistant medical director of CPCS’s San Francisco division and a UCSF assistant professor of emergency medicine. Through a pilot program under the California Department of Health Care Services, emergency clinicians can now call CPCS to get advice on administering buprenorphine. This opioid alternative treats withdrawal and helps patients stay off heroin and other riskier opioids, thus preventing overdoses. But because starting patients on buprenorphine in emergency departments is a relatively new practice, emergency providers may feel uncomfortable doing so.

“So we’re here to hold their hand,” Vo says.

A reassuring voice

It’s late afternoon now. Tsutaoka and Agustin are nearly done with their shifts. A new team of specialists has arrived.

The phone rings, and Leslie Lai, PharmD ’18, answers. The caller is distraught. Her 4-year-old son was snacking on some dried seaweed, she says, and then suddenly he was spitting out something white and granular. Lai can hear the boy screaming. “It looked like tapioca,” the mom says. The boy had eaten a packet of silica gel beads.

“They’re not toxic,” Lai tells her.

They’re not?

No.

The mom sounds bashful. “I just panicked,” she says. “I think I scared him.” The kid’s screams hit a new register. “She says it’s okay,” the mom tells him. “It’s okay. It’s all right.” The boy stops crying, and the mom hangs up.

The phone rings again.