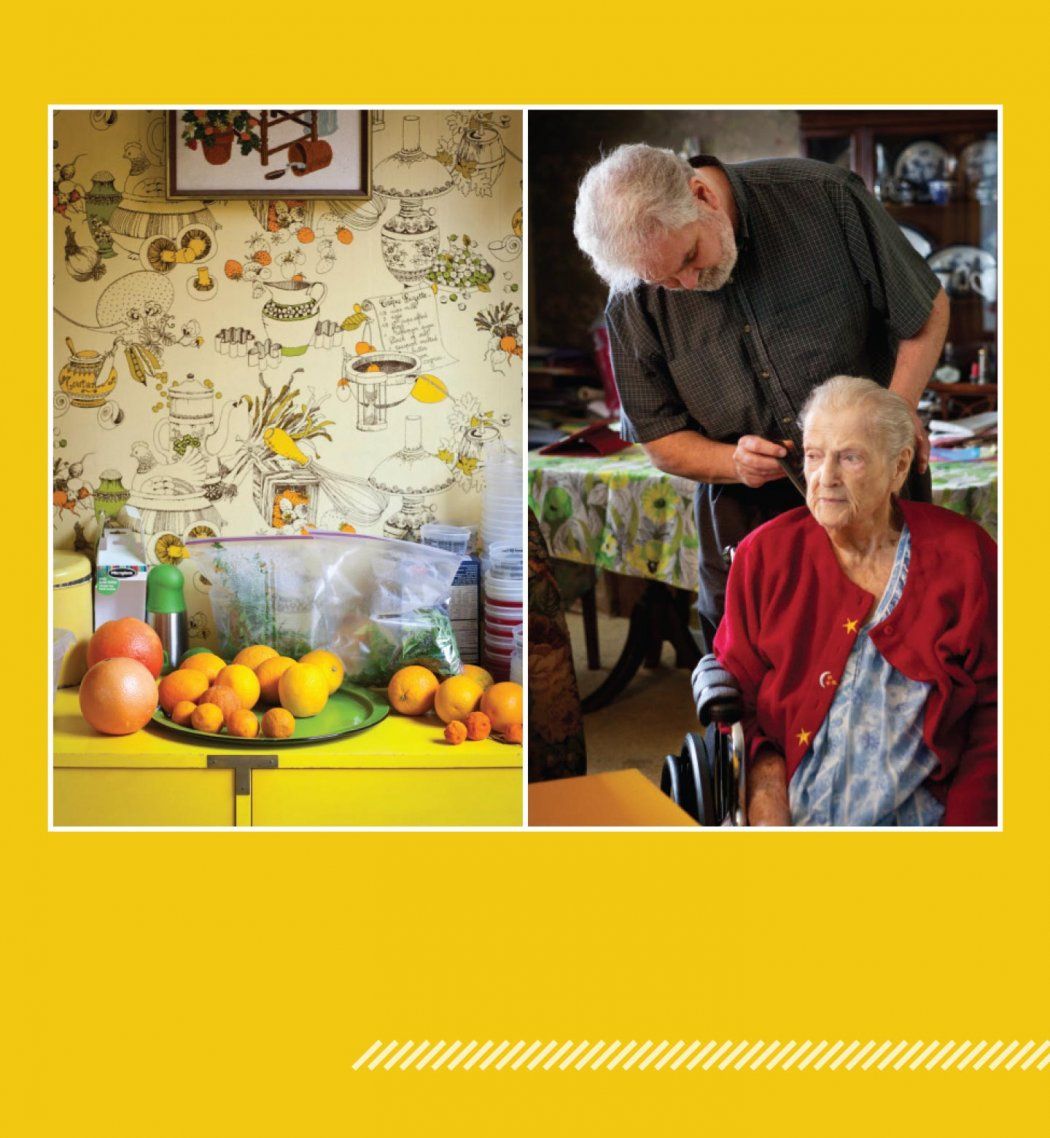

Strong-willed and a little feisty, Hellen Aitel reached her 90s enjoying a mostly self-sufficient life. Until she had surgery in 2012.

“She walked into the hospital and came home in a wheelchair,” says her son, Stephen Aitel. Hellen Aitel’s condition deteriorated further after a stint in a rehabilitation center, but she was determined to return to her home near Lake Merced in San Francisco.

The stairs in Aitel’s two-story house loomed as a major obstacle. Her son had to arrange medical transport for every doctor visit, turning a simple appointment into a stressful event that left both mother and son drained. A constellation of problems – including lack of mobility, high blood pressure, fluid in her lungs, and pain from rheumatoid arthritis – conspired to further impact her health.

That’s when geriatrician Helen Kao, MD ’03, stepped in with a powerful tool – her car.

It carries her up and down San Francisco’s hills to visit frail residents who cannot surmount the city’s steep streets, or even the precipitous steps out their own front doors. For Kao, who is the medical director of geriatric clinical programs at UC San Francisco, these visits allow her to practice the kind of care that she and her colleagues find to be best for older patients: individualized and team-based.

This approach shapes much of their work, from the flagship Housecalls program – a practice from days past that’s gaining renewed traction – to a new program for patients with complex psychosocial medical needs. And it’s an approach grounded in leading research by UCSF experts in the Division of Geriatrics who care for older people every day in clinics, hospitals, and homes. Their work – which helped UCSF Medical Center earn a top-10 ranking for geriatrics in U.S. News & World Report’s most recent survey of the nation’s best hospitals – is transforming health care for the burgeoning population of older adults in the United States.

Tailoring Care for the Silver Surge

Every day, roughly 10,000 Americans turn 65. The growth in the number of older adults is unprecedented in the history of the United States, fueled by longer life spans and the aging of the baby boom generation. For older adults, a one-size-fits-all path to health care falls short, say faculty members in UCSF’s Division of Geriatrics.

“If you’ve seen one older patient ... you’ve seen one older patient,” points out Kenneth Covinsky, MD ’88, MPH, who holds the Edmund G. Brown Sr. Distinguished Professorship in Geriatrics. “What’s right for an older person hinges on their full medical and social context.”

Two out of three older Americans have multiple chronic conditions; in fact, 95 percent of health care costs for those 65 or older are for chronic diseases.

For starters, older adults tend to need the most care, yet most medical studies exclude participants over 75, says Louise Walter, MD, a resident alumna and chief of the Division of Geriatrics. “If you do the same thing to an 85-year-old as a 50-year-old, you’re probably going to cause harm,” she explains. In studying diabetes, for example, Associate Professor Sei Lee, MD, also a resident alumnus, found that guidelines developed for managing the disease in younger people led to overly aggressive management of blood sugars in older adults, increasing their risk for hypoglycemia.

Complicating matters, many older adults are grappling with multiple chronic conditions. But most research is conducted on people with a single disease who are otherwise relatively healthy. “We’re learning that what’s right for the individual disease is often not right for the patient,” adds Covinsky.

Medication Deluge

For older patients with multiple conditions, “the medications can pile up quickly,” says Michael Steinman, MD, an associate professor and resident alumnus who studies the problems caused by simultaneous use of multiple drugs. For example, a medication used to treat one disease may have an adverse effect on another disease, or one drug may interact poorly with another.

Side effects are often indistinguishable from symptoms, he adds, which can create a troubling “prescribing cascade.” Say a patient with heart failure takes furosemide, a diuretic also known as Lasix. That can lead to urinary incontinence, so the doctor might prescribe another drug to treat that condition. But that drug could cause cognitive impairment, so the doctor might conclude that the patient has dementia. So yet another drug is prescribed to treat that problem. And on it goes. “A better approach would be stopping or changing the first drug,” Steinman explains.

Louise Walter, chief of the Division of Geriatrics (left photo); and Michael Steinman, rear, a national leader in improving how medications are prescribed for older adults with complex health problems. Photo: Elisabeth Fall

He is currently partnering with pharmacists to create evidence-based guidelines to improve how doctors prescribe medications for older adults. “We want to help make sure they don’t get too many medications or too few, but the right ones that are tailored to their needs,” he says.

Age is Not a Number

Numerical age, it turns out, is not the best guide when caring for older adults – another reason why tailoring care to the individual is so critical.

Division Chief Walter learned this early in her career when she felt stymied by cancer screening guidelines based on age. She had a robust 80-year-old patient who still enjoyed hiking but who couldn’t get a mammogram because she was over the age cut-off. Yet she also had a very frail 75-year-old patient with dementia who could. “I thought, ‘That’s crazy,’” she recalls.

Her 80-year-old patient was more likely to benefit from screening, Walter reasoned. And her dementia patient was more likely to be harmed, since inconclusive results can lead to biopsies and other invasive procedures that might exacerbate her existing illness. The dementia patient was also likely to die from dementia before an abnormality detected by screening could cause symptoms. In a series of seminal studies, Walter went on to demonstrate that life expectancy is more important than age in determining the benefits and risks of cancer screening.

Since January 2011, roughly 10,000 Americans have turned 65 every day – a rate that will continue for almost two decades.

Her work transformed national cancer screening guidelines and, more recently, led to the development by several Division of Geriatrics faculty members of an app for iPhones and iPads. Called ePrognosis: Cancer Screening, the app guides clinicians in talking with older patients about whether to start, stop, or continue screening for breast cancer and/or colorectal cancer.

Covinsky, who directs UCSF’s Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, one of only 14 centers of excellence funded by the National Institute on Aging’s Pepper Centers program, has also exposed the limits of decision-making based on age. In groundbreaking research, he demonstrated that patients’ functional status – their ability to bathe, dress, walk, eat, manage their medications, and perform other everyday tasks – is far more relevant than age in predicting their health outcomes. In addition, he’s shown that functional status – especially mobility – can reveal more about patients’ health than their diseases can.

“One of the first things I look at with patients is how they get from the waiting room to the clinic,” he says. “Before I even start thinking about their diseases, I’m thinking about how they function and what they need to function better.”

Yet even the complex mix of functional ability, diseases, medications, and life expectancy still only tells part of an older person’s health story. A slew of psychosocial conditions can interact with illness to leave an individual impaired, says Kao, the geriatric clinical programs’ medical director. All these myriad pieces must be viewed through an essential lens: the patient’s own goals.

In 2004 (the most recent data available), the 65-and-over demographic accounted for 34 percent of US health care expenditures, while making up only 11 percent of the population.

“We really try to balance what is available in our medical armamentarium with what is going to help the patient achieve their goals,” explains Kao, who is also a resident alumna. “We might be able to do some procedure, but it may never really benefit them and might actually cause harm.”

Home Team

In the end, no one health care provider can do it all.

“When you think about trying to address the kinds of issues [older adults face], the perspectives of multiple disciplines become increasingly valuable,” says Margaret Wallhagen, RN, PhD. An alumna of UCSF’s School of Nursing, she directs the UCSF/John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Gerontological Nursing Excellence.

Kao, too, understands the wisdom of casting a wide net. Last year, she partnered with UCSF’s primary care clinics to create a dream team of sorts to focus on patients with complex psychosocial medical needs. Most of the participating patients were older adults, and all ended up frequently in the hospital or emergency room – a major red flag for geriatricians. “You could pin it on our lapels: do whatever we can to keep patients out of the hospital,” says Kao. One such patient – a 71-year-old woman with coronary artery disease, hypertension, asthma, recurring vertigo, breast cancer, and a brain lesion – visited the emergency room 10 times in 12 months and was hospitalized twice.

To determine why, and to avoid such patterns in the future for these patients, Kao brought together health care providers from across UCSF: primary care physicians, geriatricians, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists. And through UCSF’s community partner, the Institute on Aging, she included social workers and psychologists, too. Each participating patient is assigned a team, which is guided by the patient’s primary care provider. To start with, a nurse practitioner and a social worker assess the patient in his or her home, then the team members meet weekly to share their expertise in developing and monitoring a highly individualized care plan.

Kao also oversees UCSF’s Housecalls program, which embodies why individualized, team-based care is effective – and is gaining steam. The number of house calls made in the United States on homebound patients covered by Medicare has grown steadily over the past decade, from 1.6 million in 2001 to 2.6 million in 2011, according to the American Academy of Home Care Physicians.

Rebecca Conant, left, an expert in the benefits of house calls. Photo: Elisabeth Fall

Staffed by geriatricians and a gerontological nurse practitioner, Housecalls serves more than 160 homebound, mostly low-income San Francisco seniors. For many, the Housecalls visits are their only lifeline to the health care system besides the emergency room. The program also connects patients with community services. “Getting people hooked up to social services is a critical part of caring for them at home,” explains Associate Professor Rebecca Conant, MD ’96, a resident alumna, and a national expert in the field.

Home visits convey the big picture, she says. “We see what’s going on in terms of family support, living conditions.... Do they have adequate food? Heat? You don’t get that in a clinic.”

The team also meets spouses, children, and caregivers; hears life stories; and learns what the patients want out of their health care as they face the twilight of their years. Knowing their goals can avoid hospital visits that might be both costly and unhelpful.

Recently, one of Conant’s patients suffered a stroke. After a long conversation with the patient’s wife, who was adamant about keeping him at home, Conant decided the best intervention was a home health referral to help with his care and with modifying his diet. The hospital could have run a battery of tests to assess the damage, but in the end that wouldn’t have made a difference in his recovery, she says. “So there was no ambulance trip, no emergency room visit, no hospitalization.”

The fastest-growing demographic in the United States is people 85 or over.

Kao’s patient Hellen Aitel became a Housecalls participant in early 2013. “It was like the clouds parted and the sun came shining through,” recalls her son, chuckling quietly. “It made everything so much easier on her – and me.

“One of the early questions Dr. Kao asked,” he continues, “was ‘What’s important?’” The list for Aitel wasn’t long: to walk again, to get relief from her arthritis pain, and to remain where she’d lived for 50 years. “My mother’s life revolved around her home,” Stephen Aitel says.

Helen Kao, director of geriatric clinical programs, while making a house call on Hellen Aitel in 2013. Photo: Elisabeth Fall

Hellen Aitel’s team included home health nurse Barbara Schubach and physical therapist Jelin Hoh. They and Kao helped the 92-year-old walk again and encouraged her to be honest about her pain. “She was afraid of being perceived as a whining little old lady,” says her son. “They were able to get through to my mom and took amazing care of her.”

Hellen Aitel also wanted to stay at home as long as possible. “And darned if they didn’t do it,” he says, choking up. She died in late 2013, peacefully, at home.

Sources for facts: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and US Census Bureau