At the risk of spoiling all suspense, you already know about the biggest threats to your health. Statistically speaking, heart disease and cancer top the list of causes of death in the U.S. That’s been the news year after year, for decades. But what about the hazards on the horizon – the lesser-known afflictions that are occurring more often? UC San Francisco experts explain some of the health concerns on the rise right now.

Click a button or scroll down to explore the hazards.

Click a button or scroll down to explore the hazards.

Meet coccidioides, the shape-shifting fungus that can turn from benign to deadly depending on its host.

Its unique ability to change form makes coccidioides, dubbed “cocci” by those who study it, dangerous. Traditionally, it’s found in the soil of the American West – mainly California and Arizona – where it thrives as a mold. But when its spores are inhaled, they can transform into a yeast able to grow inside the human body. The result: valley fever.

“When we think of a yeast infection, it sounds benign,” says Geetha Sivasubramanian, MD, chief of infectious diseases at UCSF Fresno. “But that’s not the case with valley fever. The infection starts in the lungs and can spread to the skin, bones, and brain. I’ve seen young kids with infections in their spines, and they’re paralyzed.”

A dangerous mycological outbreak might call to mind The Last of Us, HBO’s 2023 post-apocalyptic drama about a fictional version of cordyceps. That particular pandemic drives humans to bite each other, spreading disease in a rabies-like frenzy. Thankfully, cocci’s got nothing in common with that sci-fi mushroom. Common symptoms of valley fever are akin to pneumonia: fever, cough, shortness of breath, body aches.

“It’s not contagious from person to person,” Sivasubramanian says. “If two people in the same family get it, it’s because they live in an area where they’re both inhaling the fungus. Valley fever affects animals, too, but you can’t get it from your dog.”

Some people inhale a few spores and never get sick. Others aren’t so lucky. Having a compromised immune system or spending a lot of time around dusty soil increases your risk. After an outdoor music festival in Bakersfield, Calif., for example, 19 people contracted valley fever. Eight were hospitalized.

The fungus is a slow-growing pathogen, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Viruses can make you sick within days. Cocci? Think weeks.

“The test for valley fever relies on your body producing antibodies against the infection,” Sivasubramanian says. “So it may take several weeks to get a positive result.”

Because valley fever is often mistaken for pneumonia, some doctors prescribe antibiotics, which aren’t effective. And in the rare cases when it spreads to the brain, patients don’t always have obvious signs. Sometimes they only have a headache.

Cocci infections also take time to treat. Patients often need many months of therapy. And if cocci invades your brain, expect to stay on antifungal medication for life.

In high-risk areas of California, Sivasubramanian and her colleagues have been raising awareness of valley fever. To prevent infection, remember that the spores spread via dust – wet soil, not so much. Spraying down a garden, field, or construction site helps. Anyone who digs into dry dirt should wear a protective mask.

Sivasubramanian hopes to eventually establish a multidisciplinary center for treating valley fever at UCSF Fresno. In the meantime, she’s studying health disparities related to the infection – especially among farmworkers – and helping to develop better, faster tests and treatments. In the coming months, UCSF Fresno plans to enroll patients with advanced valley fever into clinical trials for medications that might have fewer side effects.

Meanwhile, scientists like Anita Sil, MD, PhD – the J. Michael Bishop, MD, Distinguished Professor of Microbiology and Immunology – are exploring cocci’s unusual response to temperature shifts and its ability to manipulate the human immune system. By understanding exactly how the fungus transforms and adapts in the lab, Sil hopes to find new ways to thwart it in the wild.

“Researchers are also looking at soil ecology and climate change,” Sivasubramanian adds. “What’s happening in California and Arizona? That could happen in other states. Every aspect of valley fever needs our attention right now.”

What’s happening in California and Arizona? That could happen in other states. Every aspect of valley fever needs our attention right now.”

“The French Pox.” “The Spanish Disease.” “The Italian Sickness.” Slang for syphilis spans centuries – and countless attempts to blame outbreaks on someone else. Lately, the infamous bacterial disease is grabbing headlines again. Between 2018 and 2022, syphilis cases in the U.S. surged by almost 80%, reaching infection levels not seen since 1950.

One of the oldest sexually transmitted illnesses, syphilis often begins with a small genital lesion. This early, painless sign tends to go away, but over time, the infection damages distant organs like the heart and brain. Before antibiotics, some late-stage syphilis patients were marred by ulcers that eroded flesh and bone. Noses fell off. People died. It was grim.

By the time Ina Park, MD, MS, a UCSF professor of family and community medicine, first started seeing patients in 1999, syphilis had declined. After penicillin became available in the 1940s, public campaigns dramatically increased diagnosis and treatment. For a while, most U.S. states required couples to get tested for syphilis before marriage.

In the late ’90s, the disease was rare enough that some physicians didn’t encounter any cases at all. The elimination of syphilis seemed close at hand, according to Park, in part because so many people were using condoms as if their lives depended on it. “In the ’80s, a lot of people were terrified of dying of AIDS,” says Park, who is also the co-principal investigator of the California Prevention Training Center, which provides free training on HIV and STIs to health care professionals. “There were no good medications for HIV. People were associating sex with death, and they adjusted their behavior accordingly.”

But as effective HIV/AIDS treatments emerged, safer sex practices began to wane. Park notes that attitudes toward condom use gradually shifted as the disease became more manageable.

“It wasn’t a death sentence anymore,” Park says. “People weren’t afraid of other STIs in the same way they feared HIV/AIDS. Other things contributed, too, like the rise of smartphones. My patients say it’s now easier to arrange a casual hookup for sex than it is to order pizza.”

Eventually, as syphilis rates climbed once again, the CDC recommended routine testing for gay and bisexual men, who had the highest prevalence. But cases started rising among women and heterosexual men, too. Data suggests that people with substance use disorders contract syphilis at higher rates. A study of women and heterosexual men diagnosed with syphilis found that their use of injectable drugs or methamphetamine more than doubled between 2013 and 2017. Both kinds of drugs are linked to riskier sexual behavior, including transactional sex.

While Park hopes more awareness might prevent infections, she says the best way to reduce syphilis is to increase testing and treatment for everyone.

“Getting an STI is sometimes just a natural consequence of being sexually active,” Park says. “All sexually active people need to get screened. STIs don’t discriminate. They can happen to anyone. And most of the time, especially with syphilis, the symptoms can be so subtle that you don’t have any idea. You can be completely asymptomatic.”

Syphilis can also be acquired by a fetus during pregnancy. Congenital syphilis has increased tenfold since 2012, disproportionately affecting Black, Hispanic, and Native American babies. In 2022 alone, over 3,700 cases were reported, and nearly 300 infants died. While prenatal testing for syphilis is required in many states, some women still struggle to get any prenatal care.

Park says efforts are underway to make syphilis testing more accessible and convenient, including at-home tests that can be mailed to a lab. The Indian Health Service has also responded, deploying public health nurses who often drive hundreds of miles to offer testing and treatment on rural reservations. Locally, a team at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital helps pregnant women with substance use disorders get prenatal care, STI screening, and addiction services.

“For people who are not likely to come to us, we need to figure out a way to go to them,” Park says. “This is such a tragedy because syphilis doesn’t require a high-tech solution that costs millions of dollars. The public health price for a penicillin injection is less than 25 cents.”

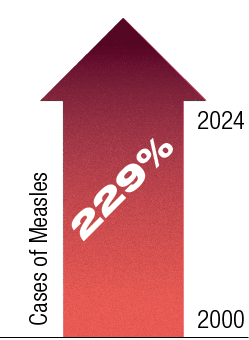

In 2000, after a year of zero transmission, U.S. officials declared measles eliminated. It was a success born of a decades-long effort to prevent the virus through widespread inoculation. The measles virus spreads readily through the air – lingering after a cough or sneeze for up to two hours – and the disease has no proven treatment. Infected people usually get a rash, fever, and respiratory symptoms, but complications can range from pneumonia to seizures to death.

Unfortunately, the American victory over measles hasn’t held up.

“People should be worried about it,” says Peter Chin-Hong, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at UCSF. “Vaccines have been one of the most impactful interventions in reducing childhood disability and death. But as vaccination rates go down, we risk reversing our progress and turning back time. Measles is a harbinger of things to come.”

Rates of routine child vaccination plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many families skipped regular doctor’s visits. But the ongoing drop in vaccination is more about a misinformation movement. Today, that movement is inextricable from politics. While most Democrats (85%) continue to support vaccine requirements for children, Republican support dropped from 79% in 2019 to 57% in 2023.

“There’s been an infusion of politics into health care,” Chin-Hong says. “They’re so intertwined now. Choosing to vaccinate or wear a mask is almost like wearing a T-shirt with a [political] message.’”

Measles is just one of many threats that American children are traditionally vaccinated against. A recent polio case in New York caused alarm that that disease, which permanently disabled about 35,000 people a year during its peak in the 1950s, might also be returning to the U.S.

To increase protection against preventable diseases, some advocate for ending nonmedical vaccine exemptions, which allow parents to opt out of mandatory child vaccinations due to religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs. After California enacted exactly this kind of law in 2016, a UCSF study found that it worked: Vaccination rates rose to 95% in most counties, restoring what public health experts call “herd immunity.”

“It’s easier for measles to find entry points in communities that are undervaccinated,” Chin-Hong says. “Herd immunity is almost like a force field. Enough people have been vaccinated as children to keep everyone safe.”

Chin-Hong thinks the U.S. would also benefit from a more centralized approach to immunization policy. While some states offer free childhood vaccines, funding and accessibility vary widely.

“This patchwork system and lack of a unified, national electronic health record make it challenging to keep track of people’s immunization status,” he says. “Where I grew up in the Caribbean, vaccines would just be delivered in schools. With health care here, you kind of have to find your own way.”

For now, Chin-Hong fears American vaccine hesitancy might not shift until outbreaks grow and strike closer to home for more people.

“Vaccination rates go up when people feel more personally at risk,” he says. “We all want what’s best for the kids, but talking to parents about the disease only gets you so far if they’re vaccine hesitant. Measles is just like, you know…who can really remember it? People born in the 1950s?”

As vaccination rates go down, we risk reversing our progress and turning back time. Measles is a harbinger of things to come.”

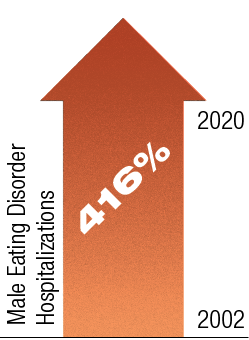

Eating disorders among women and girls have long drawn attention, prompting countless conversations about body image and how to overcome unhealthy expectations. In response, even Barbie, long critiqued as an unachievable ideal – if she were a real person, she’d have an 18-inch waist – has started to change. Mattel released its first “curvy” Barbie in 2016.

But recent research suggests that we’ve failed to notice a dramatic increase in body image issues among young men. A study of eating disorder hospitalizations between 2002 and 2020 found the largest increase in male patients, whose hospitalizations rose 416%.

“It’s part of normal development during puberty to have some concerns about body image, but this has been recognized almost exclusively in girls and women,” says Jason Nagata, MD ’13, an eating disorders expert and associate professor of pediatrics. “These pressures also exist for boys and men, and there’s more pressure today than decades ago. The idealized masculine body is now really big and muscular.”

If a Barbie doll symbolizes female body standards, it’s worth examining how male action figures have evolved over time, too. The Batman of the 1940s? He’s this average guy with a mask and cape. Today, Batman has six-pack abs and crushing biceps. His legs look like tree trunks.

Ripped superheroes aside, social media might be the biggest driver of body dissatisfaction in the 21st century. Nagata says Instagram use among boys is associated with more disordered eating, less satisfaction with their muscles, and even anabolic steroid use.

“The impact of social media is pervasive,” he says. “When I was growing up, most kids would never expect to be in a Hollywood movie or on TV or in a magazine. Now, anyone can be an influencer. And for many young people, their social lives revolve around social media.”

Recent studies of adolescent boys find that a third want to lose weight and another third are trying to gain muscle. While some weight loss or muscle attainment can be healthy, Nagata warns that excessive exercise, strict diets, and risky behaviors tied to muscle growth tend to get overlooked in men and boys.

“Physicians screen for eating disorders, but they’re typically taught to look for weight loss,” Nagata says. “Doctors are trained to ask if patients are fasting, skipping meals, or using diet pills. But none of those questions capture any of the muscularity concerns.

“And to some extent,” he adds, “extreme measures are normalized. My first male patient was a wrestler. He worked out six-plus hours a day and didn’t eat enough. His disorder hadn’t been recognized in part because everyone on his team was fasting for two days before their weigh-in. Even muscle-building substance use is relatively common in male athletes.”

Muscle dysmorphia in particular – sometimes called “reverse anorexia” – can be tough to spot. People tend to consume a lot of protein and supplements as they try to bulk up, but it’s not always clear when they’ve crossed the line into an unhealthy obsession. Those using anabolic steroids usually keep it a secret, and they’re focused on short-term muscle gains rather than long-term risks – like early heart attacks, strokes, and psychiatric problems. For those worried exclusively about looks and not longevity, note that anabolic steroids also cause male pattern baldness.

“We still need to do more research to improve care for these patients,” says Nagata. “I followed that wrestler over the course of a year. He experienced so many struggles that girls wouldn’t have faced. Many people still feel a sense of shame when they are diagnosed with an eating disorder. For boys, that stigma is often even greater because it’s viewed as a feminine illness.”

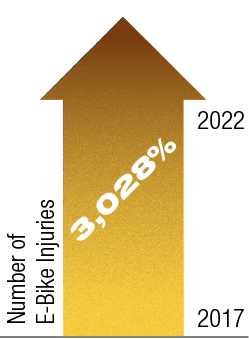

Spend time in any city, and you’ll spot them: people zipping past on electronic bikes and scooters. Maybe you’re one of them, off to run errands or get to work – no hunting for parking, no waiting for the bus! But surely you’re not the jerk soaring down the sidewalk, expecting everyone to leap out of your way. Right?

Love them or hate them, the popularity of e-bikes and e-scooters keeps growing – and “micro-mobility” injuries are more than keeping pace. A recent UCSF study found that e-bike injuries doubled every year from 2017 to 2022, while e-scooter injuries jumped by 45% annually. And helmet use dropped. Predictably, cases of e-bike riders landing in the hospital with head trauma shot up 49-fold during the same period.

Benjamin Breyer, MD, MAS ’11, senior author of the study, cites several likely reasons for the spike in injuries. First, many people opt for the convenience of renting bikes or scooters, but such services don’t encourage helmet use.

“You have to bring your own helmet, and people don’t like to lug them around,” says Breyer, who is chair of urology and the Taube Family Distinguished Professor. “The rideshare companies could rent helmets, but there are a lot of logistical challenges, particularly around hygiene.”

Another reason for accidents? Speed. E-bikes can hit up to 28 miles per hour. With greater haste comes less control, especially in urban settings where riders jostle with pedestrians and cars.

Intoxication also plays a role in some accidents. The UCSF study found that e-bike and e-scooter riders involved in accidents were more likely to have consumed alcohol compared to those injured on traditional bikes.

“I’m not sure why that is happening,” Breyer says. “Maybe people think there’s less potential for severe harm to others. But that’s misguided. E-bikes can cause serious accidents. If you’re too intoxicated to drive a car, you shouldn’t cycle either. Especially in the age of Uber, just use a rideshare or walk.”

If you’re too intoxicated to drive a car, you shouldn’t cycle either. Especially in the age of Uber, just use a rideshare or walk.”

Breyer thinks expanding bike safety education and improving cycling infrastructure – such as protected bike lanes – would reduce injuries. But he also believes we need a cultural shift, especially around using helmets. Unfortunately, it can be tough to grab people’s attention without, say, celebrity involvement.

“Think about skiing,” he says. “Sonny Bono. Natasha Richardson. Michael Schumacher. They had these really bad skiing accidents. That helped raise awareness. It encouraged people to ski safely. Now everybody wears a helmet on the slopes.”

While the surge in injuries is concerning, Breyer thinks banning e-bikes and e-scooters would be a massive mistake. Compared to cars, they’re environmentally friendly and reasonably good for you, so long as they’re used with some caution.

“I’m actually a big proponent of people riding e-bikes and e-scooters,” says Breyer. “They are here to stay and play an important role in the transportation ecosystem. The research is sometimes doom and gloom, but these are very healthy activities if done safely.

“Knowing what I know, I still ride a bike. Just holding and navigating it requires core strength and balance. You’re definitely getting a workout. And frankly, it’s fun.”

A Growing Threat in the Ground:

Valley Fever

Meet coccidioides, the shape-shifting fungus that can turn from benign to deadly depending on its host.

Its unique ability to change form makes coccidioides, dubbed “cocci” by those who study it, dangerous. Traditionally, it’s found in the soil of the American West – mainly California and Arizona – where it thrives as a mold. But when its spores are inhaled, they can transform into a yeast able to grow inside the human body. The result: valley fever.

“When we think of a yeast infection, it sounds benign,” says Geetha Sivasubramanian, MD, chief of infectious diseases at UCSF Fresno. “But that’s not the case with valley fever. The infection starts in the lungs and can spread to the skin, bones, and brain. I’ve seen young kids with infections in their spines, and they’re paralyzed.”

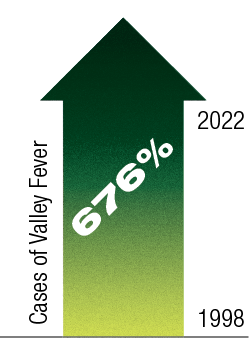

California cases of valley fever were once concentrated around the San Joaquin Valley, where UCSF Fresno is located. But cocci is spreading. Nationwide, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) logged 2,271 cocci cases in 1998. By 2022, that number had jumped to 17,612. Researchers believe climate change might be fueling cocci’s spread, enabling it to venture into states like Oregon and Washington. During droughts, soil containing the fungus turns hot and dry. The resulting dust can carry cocci into the air – and deliver it directly to your lungs.

A dangerous mycological outbreak might call to mind The Last of Us, HBO’s 2023 post-apocalyptic drama about a fictional version of cordyceps. That particular pandemic drives humans to bite each other, spreading disease in a rabies-like frenzy. Thankfully, cocci’s got nothing in common with that sci-fi mushroom. Common symptoms of valley fever are akin to pneumonia: fever, cough, shortness of breath, body aches.

“It’s not contagious from person to person,” Sivasubramanian says. “If two people in the same family get it, it’s because they live in an area where they’re both inhaling the fungus. Valley fever affects animals, too, but you can’t get it from your dog.”

Some people inhale a few spores and never get sick. Others aren’t so lucky. Having a compromised immune system or spending a lot of time around dusty soil increases your risk. After an outdoor music festival in Bakersfield, Calif., for example, 19 people contracted valley fever. Eight were hospitalized.

The fungus is a slow-growing pathogen, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Viruses can make you sick within days. Cocci? Think weeks.

“The test for valley fever relies on your body producing antibodies against the infection,” Sivasubramanian says. “So it may take several weeks to get a positive result.”

Because valley fever is often mistaken for pneumonia, some doctors prescribe antibiotics, which aren’t effective. And in the rare cases when it spreads to the brain, patients don’t always have obvious signs. Sometimes they only have a headache.

Cocci infections also take time to treat. Patients often need many months of therapy. And if cocci invades your brain, expect to stay on antifungal medication for life.

In high-risk areas of California, Sivasubramanian and her colleagues have been raising awareness of valley fever. To prevent infection, remember that the spores spread via dust – wet soil, not so much. Spraying down a garden, field, or construction site helps. Anyone who digs into dry dirt should wear a protective mask.

Sivasubramanian hopes to eventually establish a multidisciplinary center for treating valley fever at UCSF Fresno. In the meantime, she’s studying health disparities related to the infection – especially among farmworkers – and helping to develop better, faster tests and treatments. In the coming months, UCSF Fresno plans to enroll patients with advanced valley fever into clinical trials for medications that might have fewer side effects.

Meanwhile, scientists like Anita Sil, MD, PhD – the J. Michael Bishop, MD, Distinguished Professor of Microbiology and Immunology – are exploring cocci’s unusual response to temperature shifts and its ability to manipulate the human immune system. By understanding exactly how the fungus transforms and adapts in the lab, Sil hopes to find new ways to thwart it in the wild.

“Researchers are also looking at soil ecology and climate change,” Sivasubramanian adds. “What’s happening in California and Arizona? That could happen in other states. Every aspect of valley fever needs our attention right now.”

What’s happening in California and Arizona? That could happen in other states. Every aspect of valley fever needs our attention right now.”

The Resurgence of a Classic STI:

Syphilis

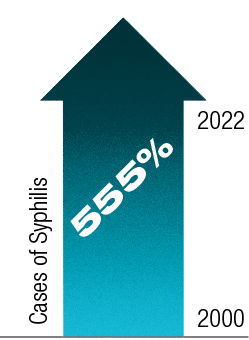

“The French Pox.” “The Spanish Disease.” “The Italian Sickness.” Slang for syphilis spans centuries – and countless attempts to blame outbreaks on someone else. Lately, the infamous bacterial disease is grabbing headlines again. Between 2018 and 2022, syphilis cases in the U.S. surged by almost 80%, reaching infection levels not seen since 1950.

In 2000, the CDC reported 31,618 cases of syphilis – adult and congenital – the lowest annual total on record. By 2022, that annual total had jumped to 207,255.

One of the oldest sexually transmitted illnesses, syphilis often begins with a small genital lesion. This early, painless sign tends to go away, but over time, the infection damages distant organs like the heart and brain. Before antibiotics, some late-stage syphilis patients were marred by ulcers that eroded flesh and bone. Noses fell off. People died. It was grim.

By the time Ina Park, MD, MS, a UCSF professor of family and community medicine, first started seeing patients in 1999, syphilis had declined. After penicillin became available in the 1940s, public campaigns dramatically increased diagnosis and treatment. For a while, most U.S. states required couples to get tested for syphilis before marriage.

In the late ’90s, the disease was rare enough that some physicians didn’t encounter any cases at all. The elimination of syphilis seemed close at hand, according to Park, in part because so many people were using condoms as if their lives depended on it. “In the ’80s, a lot of people were terrified of dying of AIDS,” says Park, who is also the co-principal investigator of the California Prevention Training Center, which provides free training on HIV and STIs to health care professionals. “There were no good medications for HIV. People were associating sex with death, and they adjusted their behavior accordingly.”

But as effective HIV/AIDS treatments emerged, safer sex practices began to wane. Park notes that attitudes toward condom use gradually shifted as the disease became more manageable.

“It wasn’t a death sentence anymore,” Park says. “People weren’t afraid of other STIs in the same way they feared HIV/AIDS. Other things contributed, too, like the rise of smartphones. My patients say it’s now easier to arrange a casual hookup for sex than it is to order pizza.”

Eventually, as syphilis rates climbed once again, the CDC recommended routine testing for gay and bisexual men, who had the highest prevalence. But cases started rising among women and heterosexual men, too. Data suggests that people with substance use disorders contract syphilis at higher rates. A study of women and heterosexual men diagnosed with syphilis found that their use of injectable drugs or methamphetamine more than doubled between 2013 and 2017. Both kinds of drugs are linked to riskier sexual behavior, including transactional sex.

While Park hopes more awareness might prevent infections, she says the best way to reduce syphilis is to increase testing and treatment for everyone.

“Getting an STI is sometimes just a natural consequence of being sexually active,” Park says. “All sexually active people need to get screened. STIs don’t discriminate. They can happen to anyone. And most of the time, especially with syphilis, the symptoms can be so subtle that you don’t have any idea. You can be completely asymptomatic.”

Syphilis can also be acquired by a fetus during pregnancy. Congenital syphilis has increased tenfold since 2012, disproportionately affecting Black, Hispanic, and Native American babies. In 2022 alone, over 3,700 cases were reported, and nearly 300 infants died. While prenatal testing for syphilis is required in many states, some women still struggle to get any prenatal care.

Park says efforts are underway to make syphilis testing more accessible and convenient, including at-home tests that can be mailed to a lab. The Indian Health Service has also responded, deploying public health nurses who often drive hundreds of miles to offer testing and treatment on rural reservations. Locally, a team at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital helps pregnant women with substance use disorders get prenatal care, STI screening, and addiction services.

“For people who are not likely to come to us, we need to figure out a way to go to them,” Park says. “This is such a tragedy because syphilis doesn’t require a high-tech solution that costs millions of dollars. The public health price for a penicillin injection is less than 25 cents.”

An Almost-Overcome Malady:

Measles

In 2000, after a year of zero transmission, U.S. officials declared measles eliminated. It was a success born of a decades-long effort to prevent the virus through widespread inoculation. The measles virus spreads readily through the air – lingering after a cough or sneeze for up to two hours – and the disease has no proven treatment. Infected people usually get a rash, fever, and respiratory symptoms, but complications can range from pneumonia to seizures to death.

Unfortunately, the American victory over measles hasn’t held up.

Despite vaccine mandates in many states, childhood vaccination rates have dropped, and measles outbreaks have ticked back up. In 2024, more than 280 measles cases were reported in 32 states. Almost half of the patients were hospitalized, including 82 children.

“People should be worried about it,” says Peter Chin-Hong, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at UCSF. “Vaccines have been one of the most impactful interventions in reducing childhood disability and death. But as vaccination rates go down, we risk reversing our progress and turning back time. Measles is a harbinger of things to come.”

Rates of routine child vaccination plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many families skipped regular doctor’s visits. But the ongoing drop in vaccination is more about a misinformation movement. Today, that movement is inextricable from politics. While most Democrats (85%) continue to support vaccine requirements for children, Republican support dropped from 79% in 2019 to 57% in 2023.

“There’s been an infusion of politics into health care,” Chin-Hong says. “They’re so intertwined now. Choosing to vaccinate or wear a mask is almost like wearing a T-shirt with a [political] message.’”

Measles is just one of many threats that American children are traditionally vaccinated against. A recent polio case in New York caused alarm that that disease, which permanently disabled about 35,000 people a year during its peak in the 1950s, might also be returning to the U.S.

To increase protection against preventable diseases, some advocate for ending nonmedical vaccine exemptions, which allow parents to opt out of mandatory child vaccinations due to religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs. After California enacted exactly this kind of law in 2016, a UCSF study found that it worked: Vaccination rates rose to 95% in most counties, restoring what public health experts call “herd immunity.”

“It’s easier for measles to find entry points in communities that are undervaccinated,” Chin-Hong says. “Herd immunity is almost like a force field. Enough people have been vaccinated as children to keep everyone safe.”

Chin-Hong thinks the U.S. would also benefit from a more centralized approach to immunization policy. While some states offer free childhood vaccines, funding and accessibility vary widely.

“This patchwork system and lack of a unified, national electronic health record make it challenging to keep track of people’s immunization status,” he says. “Where I grew up in the Caribbean, vaccines would just be delivered in schools. With health care here, you kind of have to find your own way.”

For now, Chin-Hong fears American vaccine hesitancy might not shift until outbreaks grow and strike closer to home for more people.

“Vaccination rates go up when people feel more personally at risk,” he says. “We all want what’s best for the kids, but talking to parents about the disease only gets you so far if they’re vaccine hesitant. Measles is just like, you know…who can really remember it? People born in the 1950s?”

As vaccination rates go down, we risk reversing our progress and turning back time. Measles is a harbinger of things to come.”

The Overlooked Image Issue:

Male Eating Disorders

Eating disorders among women and girls have long drawn attention, prompting countless conversations about body image and how to overcome unhealthy expectations. In response, even Barbie, long critiqued as an unachievable ideal – if she were a real person, she’d have an 18-inch waist – has started to change. Mattel released its first “curvy” Barbie in 2016.

But recent research suggests that we’ve failed to notice a dramatic increase in body image issues among young men. A study of eating disorder hospitalizations between 2002 and 2020 found the largest increase in male patients, whose hospitalizations rose 416%.

“It’s part of normal development during puberty to have some concerns about body image, but this has been recognized almost exclusively in girls and women,” says Jason Nagata, MD ’13, an eating disorders expert and associate professor of pediatrics. “These pressures also exist for boys and men, and there’s more pressure today than decades ago. The idealized masculine body is now really big and muscular.”

If a Barbie doll symbolizes female body standards, it’s worth examining how male action figures have evolved over time, too. The Batman of the 1940s? He’s this average guy with a mask and cape. Today, Batman has six-pack abs and crushing biceps. His legs look like tree trunks.

Ripped superheroes aside, social media might be the biggest driver of body dissatisfaction in the 21st century. Nagata says Instagram use among boys is associated with more disordered eating, less satisfaction with their muscles, and even anabolic steroid use.

“The impact of social media is pervasive,” he says. “When I was growing up, most kids would never expect to be in a Hollywood movie or on TV or in a magazine. Now, anyone can be an influencer. And for many young people, their social lives revolve around social media.”

Recent studies of adolescent boys find that a third want to lose weight and another third are trying to gain muscle. While some weight loss or muscle attainment can be healthy, Nagata warns that excessive exercise, strict diets, and risky behaviors tied to muscle growth tend to get overlooked in men and boys.

Medical guidelines for eating disorders remain rooted in research on women and girls. Until 2013, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders listed loss of menstruation as one of the criteria for anorexia nervosa. That’s why Jason Nagata and other experts are leading efforts to make these guidelines more inclusive. Unfortunately, UCSF is still one of only a few institutions studying male eating disorders – including how many calories male patients can safely consume after periods of starvation.

“Physicians screen for eating disorders, but they’re typically taught to look for weight loss,” Nagata says. “Doctors are trained to ask if patients are fasting, skipping meals, or using diet pills. But none of those questions capture any of the muscularity concerns.

“And to some extent,” he adds, “extreme measures are normalized. My first male patient was a wrestler. He worked out six-plus hours a day and didn’t eat enough. His disorder hadn’t been recognized in part because everyone on his team was fasting for two days before their weigh-in. Even muscle-building substance use is relatively common in male athletes.”

Muscle dysmorphia in particular – sometimes called “reverse anorexia” – can be tough to spot. People tend to consume a lot of protein and supplements as they try to bulk up, but it’s not always clear when they’ve crossed the line into an unhealthy obsession. Those using anabolic steroids usually keep it a secret, and they’re focused on short-term muscle gains rather than long-term risks – like early heart attacks, strokes, and psychiatric problems. For those worried exclusively about looks and not longevity, note that anabolic steroids also cause male pattern baldness.

“We still need to do more research to improve care for these patients,” says Nagata. “I followed that wrestler over the course of a year. He experienced so many struggles that girls wouldn’t have faced. Many people still feel a sense of shame when they are diagnosed with an eating disorder. For boys, that stigma is often even greater because it’s viewed as a feminine illness.”

The Totally Unsurprising Trend:

E-bike Injuries

Spend time in any city, and you’ll spot them: people zipping past on electronic bikes and scooters. Maybe you’re one of them, off to run errands or get to work – no hunting for parking, no waiting for the bus! But surely you’re not the jerk soaring down the sidewalk, expecting everyone to leap out of your way. Right?

Love them or hate them, the popularity of e-bikes and e-scooters keeps growing – and “micro-mobility” injuries are more than keeping pace. A recent UCSF study found that e-bike injuries doubled every year from 2017 to 2022, while e-scooter injuries jumped by 45% annually. And helmet use dropped. Predictably, cases of e-bike riders landing in the hospital with head trauma shot up 49-fold during the same period.

Some safety advocates are pushing for stricter regulations on e-bikes and e-scooters, but no national laws exist yet. Approved in September, California Assembly Bill 2234 enables counties to launch pilot safety programs that ban children under age 12 from operating an e-bike.

Benjamin Breyer, MD, MAS ’11, senior author of the study, cites several likely reasons for the spike in injuries. First, many people opt for the convenience of renting bikes or scooters, but such services don’t encourage helmet use.

“You have to bring your own helmet, and people don’t like to lug them around,” says Breyer, who is chair of urology and the Taube Family Distinguished Professor. “The rideshare companies could rent helmets, but there are a lot of logistical challenges, particularly around hygiene.”

Another reason for accidents? Speed. E-bikes can hit up to 28 miles per hour. With greater haste comes less control, especially in urban settings where riders jostle with pedestrians and cars.

Intoxication also plays a role in some accidents. The UCSF study found that e-bike and e-scooter riders involved in accidents were more likely to have consumed alcohol compared to those injured on traditional bikes.

“I’m not sure why that is happening,” Breyer says. “Maybe people think there’s less potential for severe harm to others. But that’s misguided. E-bikes can cause serious accidents. If you’re too intoxicated to drive a car, you shouldn’t cycle either. Especially in the age of Uber, just use a rideshare or walk.”

If you’re too intoxicated to drive a car, you shouldn’t cycle either. Especially in the age of Uber, just use a rideshare or walk.”

Breyer thinks expanding bike safety education and improving cycling infrastructure – such as protected bike lanes – would reduce injuries. But he also believes we need a cultural shift, especially around using helmets. Unfortunately, it can be tough to grab people’s attention without, say, celebrity involvement.

“Think about skiing,” he says. “Sonny Bono. Natasha Richardson. Michael Schumacher. They had these really bad skiing accidents. That helped raise awareness. It encouraged people to ski safely. Now everybody wears a helmet on the slopes.”

While the surge in injuries is concerning, Breyer thinks banning e-bikes and e-scooters would be a massive mistake. Compared to cars, they’re environmentally friendly and reasonably good for you, so long as they’re used with some caution.

“I’m actually a big proponent of people riding e-bikes and e-scooters,” says Breyer. “They are here to stay and play an important role in the transportation ecosystem. The research is sometimes doom and gloom, but these are very healthy activities if done safely.

“Knowing what I know, I still ride a bike. Just holding and navigating it requires core strength and balance. You’re definitely getting a workout. And frankly, it’s fun.”