Searching for the Silver Bullet

Infectious disease physician Annie Luetkemeyer leads a team of UCSF clinical researchers in testing promising therapies for COVID-19.

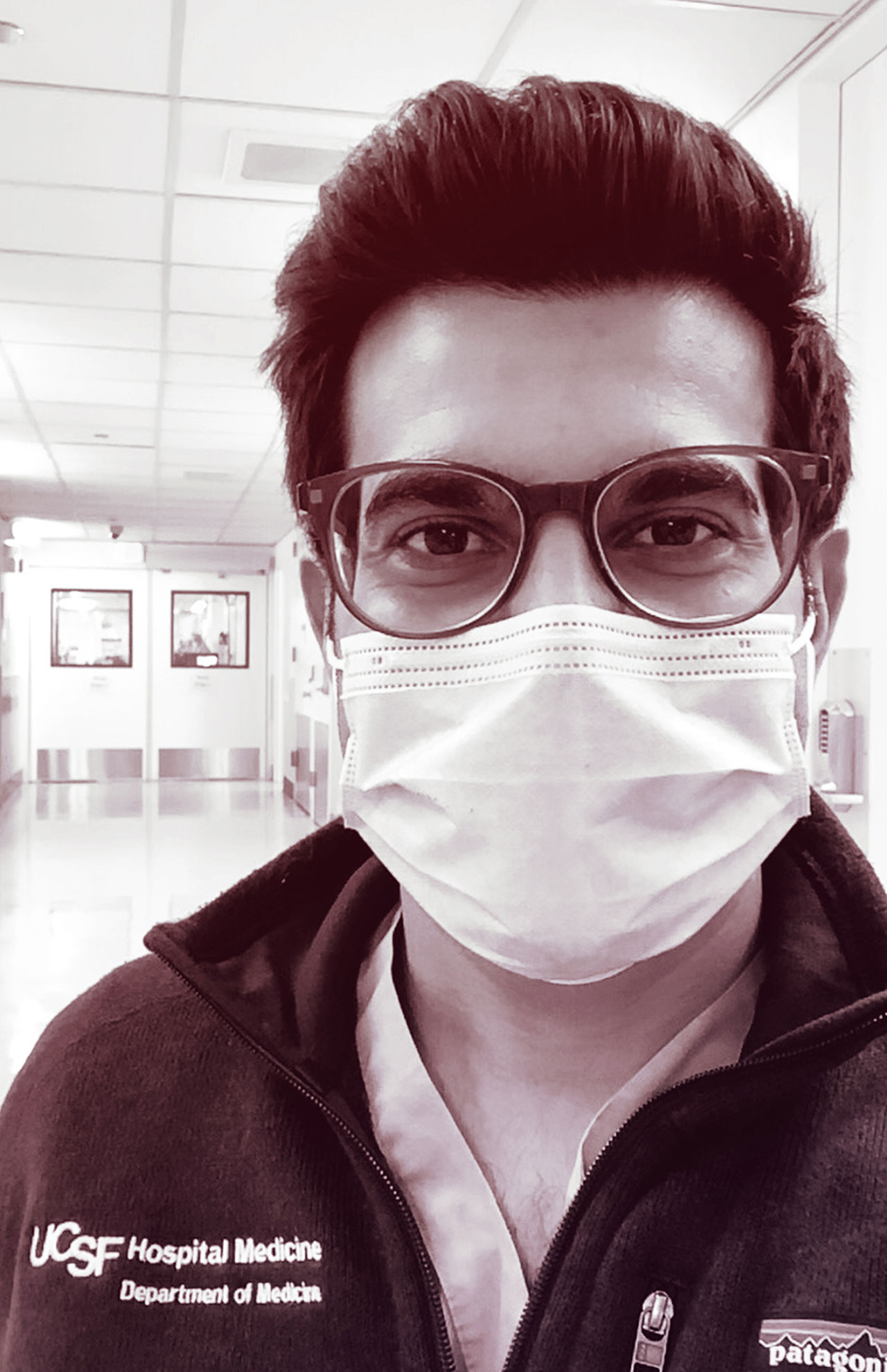

Annie Luetkemeyer, captured via FaceTime in a patient exam room at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital on June 9 at 5:15 p.m. by photographer Steve Babuljak

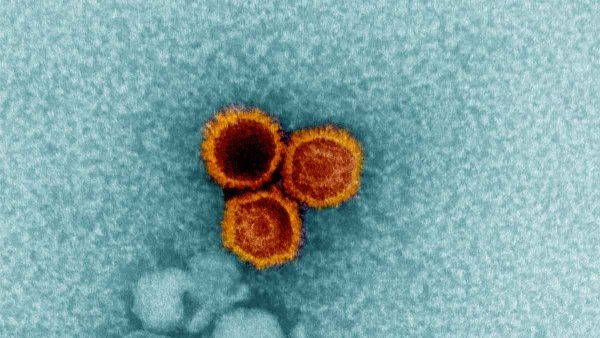

It’s a rare day when Annie Luetkemeyer, MD, puts in fewer than 12 hours at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. A UCSF physician-researcher, Luetkemeyer previously helped advance effective HIV drugs and a cure for hepatitis C. She is now leading clinical trials of promising therapies for COVID-19, including the antiviral drug remdesivir and convalescent plasma, and will soon be running vaccine trials.

When I scheduled this interview, she said she was “working around the clock” but could talk during her morning commute into the city from her home in San Mateo. While driving up the traffic-free Highway 101, the sun rising over the bay, she described the excitement and challenges of her team’s search for lifesaving medicines.

What’s your background, and what are you doing now?

I’m a bit of a hybrid between a clinician and a clinical researcher. I’m the primary care doctor for 50 to 60 patients who have HIV. And I run two research units at the General. We do clinical studies of HIV, viral hepatitis, and other infectious diseases.

Before COVID, I was really excited about a new trial called DoxyPEP, looking at an oral antibiotic called doxycycline to prevent bacterial sexually transmitted diseases in men who have sex with men. We had just enrolled 100 people. We were off to the races, and then COVID hit.

When did you realize life was about to change?

When we got our first COVID patient at the General the first week of March. This person hadn’t traveled to China and hadn’t been on a cruise ship. It became clear it was community transmission – the tip of a potentially very big iceberg.

Shortly after, we started to see substantial numbers of patients admitted to the hospital with COVID. Unfortunately, it quickly became clear that this was going to be a disease of disparities, with Latinx and African American populations disproportionately impacted.

What did you do?

We got a study up and running as part of an NIH-funded international trial of remdesivir. Remdesivir is an antiviral medicine that’s given intravenously. It had been tested during the Ebola epidemic but was not shown to have efficacy in that case. Some Seattle hospitals had given it on a compassionate use basis to a few initial COVID patients. I think everyone thought, “We have no treatments; we need a plan A, and remdesivir is certainly a promising candidate.”

So we scrambled to get our study going. We had to start from the ground up and get staff and structure in place in a very short time at both San Francisco General and the UCSF campus. We had medical students help out, we had nurses come from other units, and study physicians pivoted to dedicate time to this work. The study team was just remarkable. We asked them to basically drop everything and do this 24 hours a day, and they did. Everybody just said, “We have to do it. This is our chance to give people a possibly lifesaving drug and to learn how we can fight this epidemic.”

How did you enroll patients?

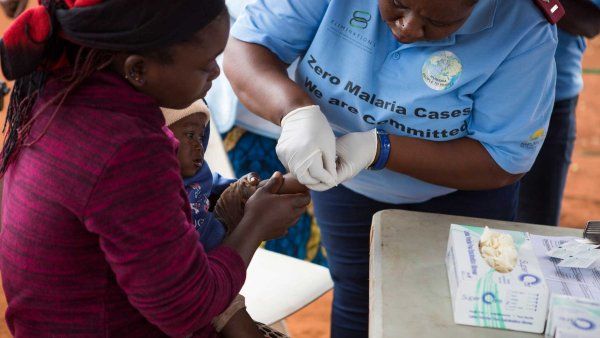

San Francisco General is a safety net hospital that serves diverse and often vulnerable populations, including those that are socioeconomically disadvantaged, are unhoused, and have limited or no English proficiency. Many patients admitted with COVID have had few previous interactions with health care. It was essential to make sure they knew they were signing up for COVID studies so they could make an informed decision about participating. For example, many people I talked to were not yet familiar with the concept of a placebo or randomization in a clinical trial.

Many times, people would say, “I don’t understand. You’re telling me you have a drug that might work. Can’t you just give it to me?” I had to explain, “We don’t know if this medicine works. That’s why we need to do this as a randomized controlled trial.” It was remarkable that despite being sick and scared, many patients said, “All right, I want to participate, even if this study may not help me, so I can help others.” Clinical trial participants are the unsung heroes in medicine, certainly in the COVID epidemic; they are the reason we’re making progress toward better treatments for COVID.

What did the remdesivir trial show?

We were delighted to see that remdesivir sped up the time to recovery – from 15 days to 11 days. The full data set isn’t out yet, but remdesivir looks safe and shows activity against COVID-19.

Clearly, though, it’s not a silver bullet. Even people who got remdesivir had a 7% mortality rate. This tells us we need to keep looking for better strategies to effectively treat COVID patients.

Infectious disease expert Annie Luetkemeyer discusses the evidence behind potential treatments for COVID-19 with Bob Wachter, chair of the UCSF Department of Medicine, on March 24, 2020.

In May, the FDA authorized remdesivir for emergency use. What does that mean?

It means the drug can be used outside of clinical trials under a special temporary authorization. We can give it to patients who meet the criteria. It’s not fully FDA-approved because the data is preliminary.

In a perfect world, I’d like to give remdesivir to every hospitalized patient, if they want it and it’s appropriate for them. Unfortunately, there’s a limited supply, and it can take months to make; we may face shortages in the months ahead if case counts rise and we aren’t able to speed up production.

What other treatments are in the pipeline?

We just completed a second phase of the remdesivir study. This time, everybody received remdesivir, and half of the participants got an anti-inflammatory drug called baricitinib. We see a lot of inflammation with COVID-19, especially in those who are critically ill. Adding an anti-inflammatory may work better than remdesivir alone.

We’re also excited about an ongoing trial of convalescent plasma that we’re running at San Francisco General and the UCSF campuses. Plasma is a blood component that contains antibodies; we collect it from people who have recovered from COVID and then transfuse it into people who are sick. The hope is that it will help speed patients’ recovery and keep their illness from worsening. It is important for people who have recovered from COVID to know that they may be eligible to donate plasma to help someone who’s currently sick with COVID; local blood banks like the American Red Cross and Vitalant have active programs to collect convalescent plasma.

Meanwhile, we’ll be starting a number of studies of monoclonal antibodies. These are antibodies designed to be very specific for COVID. Several companies have promising agents that will very soon be in clinical trials in both hospitals and outpatient settings.

When will vaccine trials start?

This summer. UCSF will be participating in several vaccine trials locally, and trials will also be conducted nationwide and internationally. So if you want access to a vaccine and to be part of this research, keep an eye out for studies in your area – there will be many chances to participate.

Would you say your outlook for the future is more “glass half full” or “glass half empty”?

Both. “Glass half empty” is what we’re bracing for. We don’t yet have a cure. We don’t yet have a vaccine. We have a treatment, but it’s not yet the silver bullet we’d like to have. It’s really heartbreaking to see this disease continue to progress. At the same time, it’s heartening to see people coming together to figure out the best way to advance the science and care for patients, as well as stepping up to participate in studies and support COVID work. And the pace at which our understanding is growing is remarkable.

More from this Series

Hospitalist Sajan Patel, MD, remembers anxieties and revelations while caring for the Bay Area’s first coronavirus patients.