Healing the San Joaquin Valley

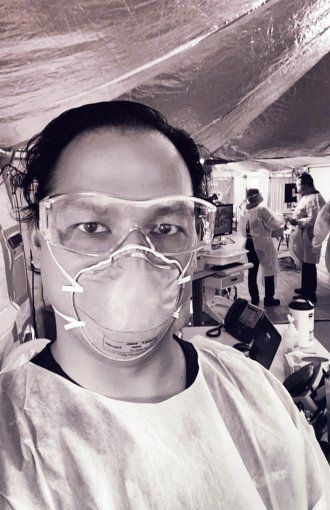

In a region where doctors are in short supply and poor health is widespread, UCSF Fresno physician Kenny Banh fights both COVID-19 and inequity.

The San Joaquin Valley, our nation’s agricultural wellspring, is one of the poorest and least healthy regions of California. It is also “physician-starved,” says Kenny Banh, MD, an emergency medicine specialist and assistant dean at UCSF Fresno.

Banh, whose immigrant parents worked in factories, helps fill that gap at a bustling safety net hospital in Fresno. It’s one of several partner hospitals where UCSF Fresno – a branch campus of UCSF School of Medicine – delivers care for the valley’s underserved populations. In early April, the coronavirus was roiling Banh’s ER and upending life for his vulnerable patients. Within weeks, he’d formulated a plan to help thwart its assault. We caught up with Banh in early June.

You’re a busy ER doc, an educator at UCSF Fresno, and the father of three young boys. How are you holding up?

People are always wondering if I’m OK. I’m great, because this is why I went into medicine – to take care of really sick patients. It sounds corny, but I love it.

Frontline doctors get recognized all the time, and I’m grateful for that. But I’ll tell you who my health care hero is – a janitor at my hospital. This guy works like a machine. He turns over rooms, he flies around scrubbing floors. He’s working for barely above minimum wage, and he’s laying his heart out for it. He’s the one keeping me safe.

UCSF Fresno is the biggest provider of care for the underserved in the San Joaquin Valley. How many patients does your hospital’s emergency department serve?

I work at Community Regional Medical Center (CRMC), UCSF Fresno’s biggest partner hospital. Our emergency department sees about 115,000 patients a year. To put that in perspective, UCSF’s largest teaching hospital sees about half of that volume. That’s a complete shock to most people. They think Fresno would run a small system, but we’re the only Level I Trauma Center between LA and San Francisco.

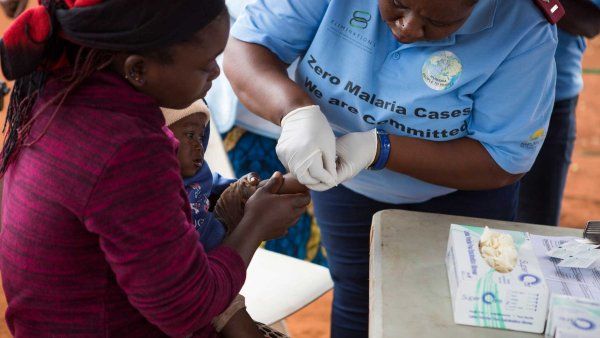

In early April, CRMC erected triage tents to prepare for a surge of COVID-19 patients. How did that play out?

Our cases never spiked, but they have grown incrementally. COVID is now an everyday diagnosis. We still have five tents connected with walkways. Today, we’re hitting 107 degrees in Fresno. Despite air conditioners, it’s like an oven in those things!

Who are your patients, and what are some of the challenges they face?

Many are undocumented and have no access to medications or insurance. We’re their only access to care. And roughly half the patient population in the valley is on Medi-Cal. Many of our patients live paycheck to paycheck. They can’t self-isolate. They can’t work from home.

What are some of the health problems in the valley that make COVID-19 especially dangerous?

We have high asthma rates, which are tied to poor air quality. We don’t create this bad air; the wind carries it from LA and the Bay Area, and the surrounding mountains trap it. Valley fever, a fungal lung disease, is also pretty prevalent. Imagine if coronavirus knocks out half your lung capacity. If you don’t have full capacity to begin with, you might not have the reserve to survive.

COVID-19 is hitting the Latino population hard. Are you seeing that in the ER?

If you look at hospitalizations, the percentage of Latino patients is fairly high. If you look at what I call the “worried well” – the people who walk into the ER who think they might have been exposed – they are predominately not Latino.

It’s a systemic issue. In general, our Latino and African American community members are disproportionately working hourly jobs that don’t offer sick leave or health insurance. For them, how is finding out if you are positive for COVID a good thing? I’m not saying it’s right. We should be testing, but it’s a real issue.

Is it hard to access testing in your area?

A lot of the clinics for the underserved do not test for COVID – they don’t have the staffing, training, or equipment.

If you look at a map of Fresno, most testing sites are in well-off districts. Drive-through clinics, for example, which are well intentioned, exclude people who don’t drive or who can’t use an app in English to schedule an appointment.

You have a plan to improve access to testing. Can you tell me about that?

I run a free mobile clinic, which we had to shut down when the coronavirus hit. Now I’m trying to get funding to convert it to a mobile testing clinic for at-risk populations: our Latino and African American communities, our undocumented farmworkers, and our homeless community.

What are you learning as you get your mobile clinic up and running?

You’d think free testing would be welcomed with open arms, but it’s not. Take farms with migrant workers. The workers need to get paid so they can eat tomorrow, and the farms don’t want to lose their workforce. So you have to think about testing from a societal standpoint, not just a public health standpoint.

How do people apply for emergency Medi-Cal? Who qualifies for unemployment benefits? Can we walk people through that? If I don’t build that support into the system, then testing is going to be shunned.

Getting back to the ER, how has the pandemic changed the way you care for people?

Wearing masks and face shields disconnects us from patients. I used to shake every patient’s hand as a sign of respect. Taking away that touch feels dehumanizing. It’s a real struggle for most health care workers. I don’t know if anyone has mastered it, truthfully.

What keeps you going?

I get to do a job I love, and I feel my work has a purpose. I thank my lucky stars every day. Then I go home, I shower, I change clothes, and I hug my kids.

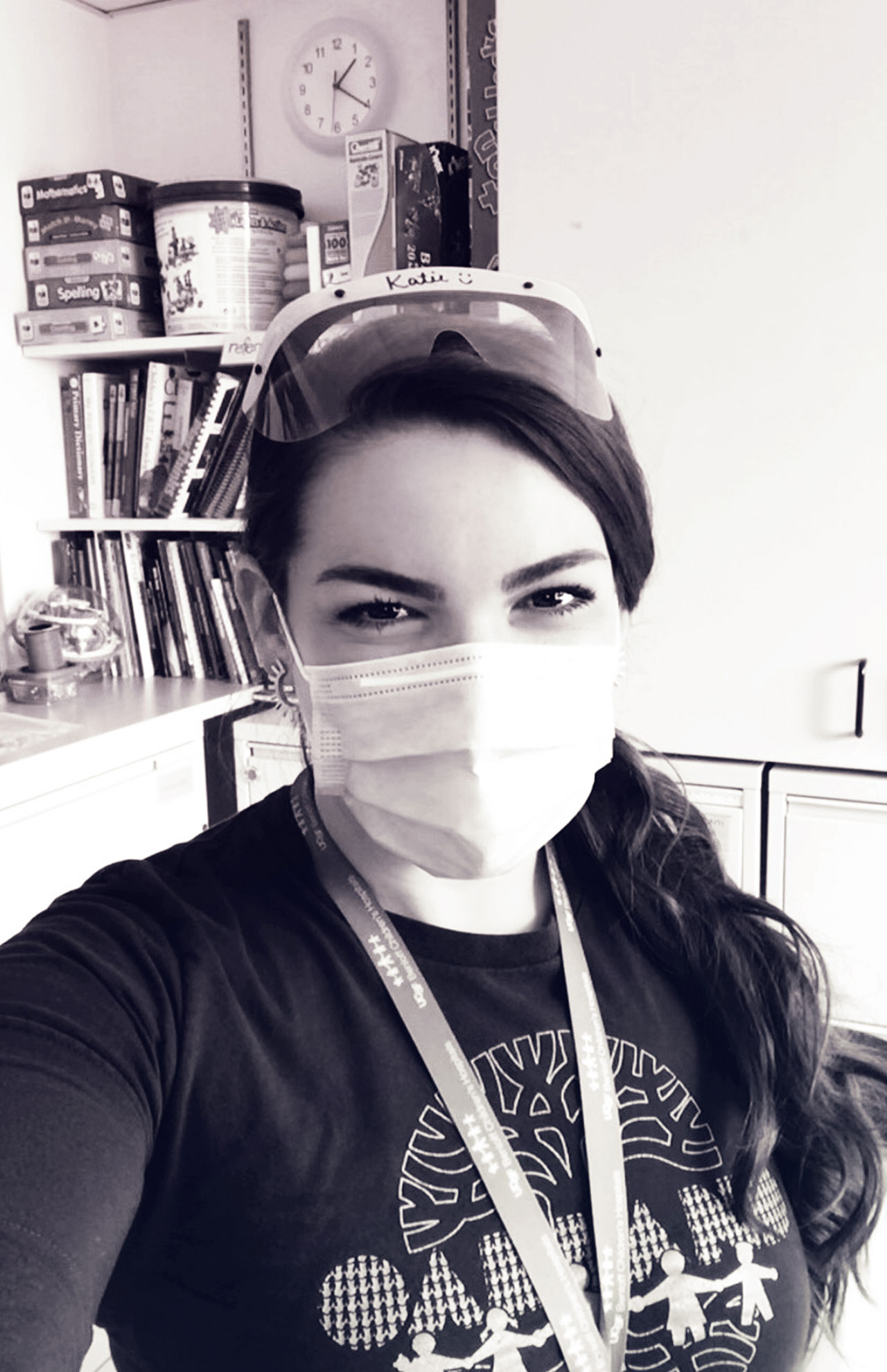

More from this Series

Child life specialist Katie Craft helps young patients grapple with new fears.