Should anyone doubt America’s mounting health crisis, a new report from the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine makes it crystal clear. On average, Americans of all ages die sooner and experience higher rates of disease than people in 16 other rich countries.

Even advantaged Americans with health insurance, college educations, and higher incomes appear to be sicker than their peers in other wealthy nations. While the reasons are varied and potential solutions complex, experts at UC San Francisco are proving that your mother’s admonishments – eat your vegetables, get off your duff, quiet down – may be just the prescription this nation needs.

Turns out, a healthy lifestyle can not only keep illness at bay, but it may even stop a disease like cancer dead in its tracks.

Healthy Living Halts Disease

UCSF has long led the way in demonstrating the positive effects of living a healthy lifestyle.

Dean Ornish, MD, UCSF clinical professor of medicine and founder of the nonprofit Preventive Medicine Research Institute, was still in medical school when he witnessed a disturbing trend: a growing number of heart disease patients were having repeat bypass surgeries. Wondering what would happen if these patients stopped smoking and began to eat better, exercise more, manage their stress, and expand their social support networks, Ornish turned his curiosity into a first-ever study – with profound results.

Through this initial study and many since, he showed the arteries of heart disease patients become less clogged and their blood flow increases, effectively reversing their disease.

Peter Carroll, the Ken and Donna Derr–Chevron Texaco Distinguished Professor in Prostate Cancer. Photo: UCSF DMM

Today, UCSF scientists across the disease spectrum are proving that a healthy lifestyle can have drug-like potency, among them Peter Carroll, MD, Department of Urology chair and co-leader of the Prostate Cancer Program at the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. Carroll, a resident alumnus, partnered with Ornish and the late William Fair, MD, of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in a major clinical trial that evaluated the effects of comprehensive lifestyle changes on prostate cancer.

The team enrolled 93 men under “active surveillance,” whose doctors had caught their prostate cancer early enough to opt for regular monitoring through blood tests and biopsies, instead of the harsh surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy needed for later-stage cancers.

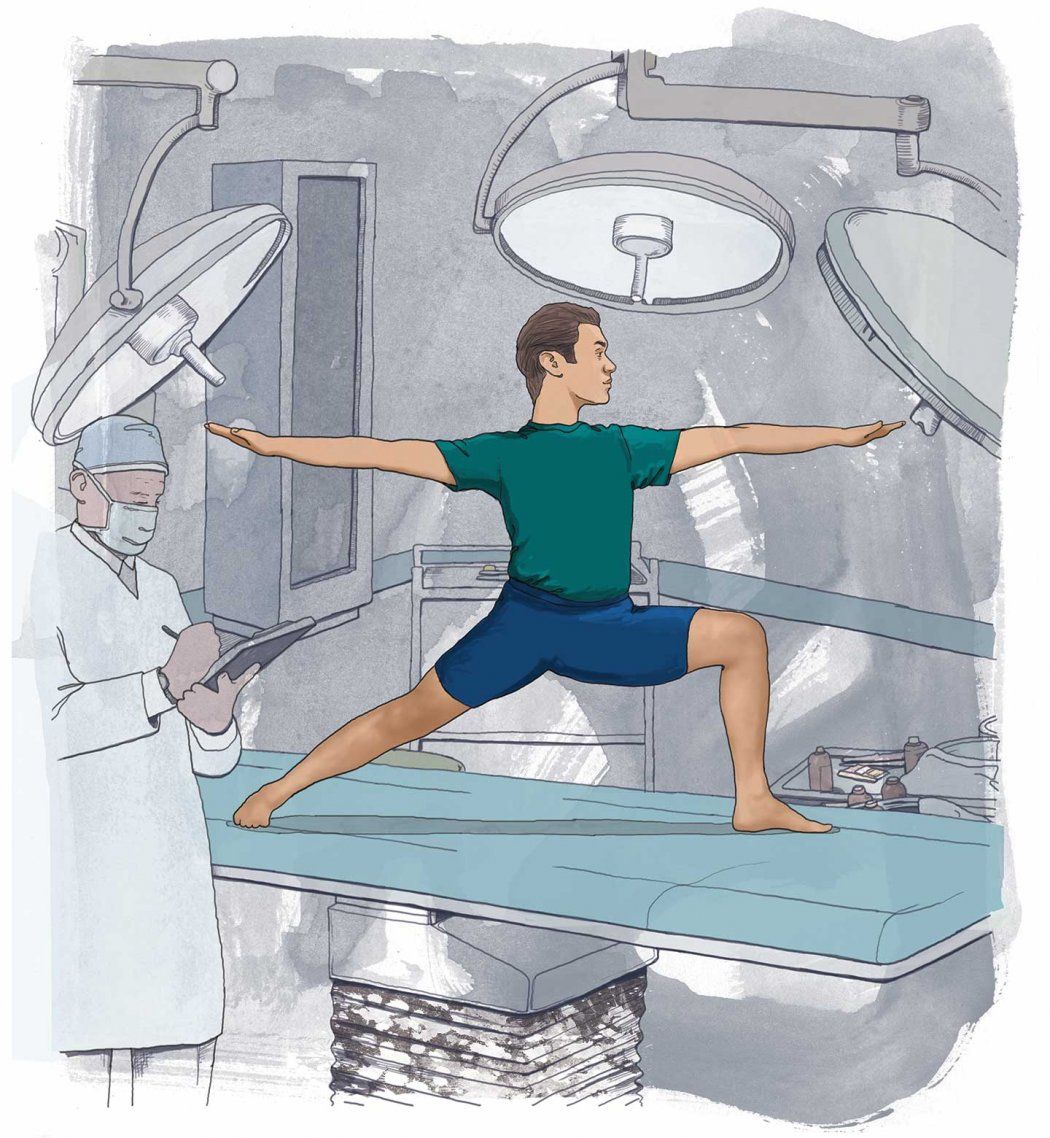

Participants fell into two groups; one was asked to make comprehensive lifestyle changes, the other was not. Patients in the healthy lifestyle group participated in the same program Ornish developed for reversing heart disease – moderate aerobic exercise, yoga or meditation, a weekly support group session, and a low-fat vegan diet consisting primarily of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes supplemented with soy, vitamins, and minerals.

Three short months later, the team observed a genetic change among men in the healthy lifestyle group. “More than 500 genes changed, and they moved in a beneficial direction every time,” says Ornish. “In particular, the genes that promote heart disease, prostate cancer, breast cancer, colon cancer, and diabetes were down-regulated, or ‘turned off,’ and other genes that discourage the development of these diseases were up-regulated, or ‘turned on.’”

After one year, the team found that prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, a protein marker indicating the presence of prostate cancer, decreased in the healthy lifestyle group but increased in the other. The more closely participants in the first group followed the recommendations, the more their PSA decreased. When the team took serum (blood plasma) from participants in both groups and placed it in a petri dish with an unrelated prostate tumor sample, they observed that serum from the healthy lifestyle group inhibited the sample’s growth by 70 percent, while the control group serum restrained it by only 9 percent.

“I tell my patients there’s evidence that if you change your diet and exercise you may both prevent cancer and change its progression once you have it,” says Carroll. “Depending on the degree of cancer, it can be done in conjunction with standard treatment, or for some people it could be in lieu of immediate treatment.”

One such patient was Jack McClure, 68, a participant in the UCSF trial. At age 57, in view of his family history of heart disease, McClure was advised by his doctor to follow the Ornish program from a book, but he couldn’t stay the course. “I lasted three weeks,” he says.

When McClure was eventually diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer and offered a spot in the trial, he took it, and got serious. By the end of the trial, his prostate cancer was arrested. With a corresponding decline in blood pressure and 28-pound weight loss, McClure’s risk of heart disease complications dramatically decreased as well.

McClure attributes his ultimate success in sticking with the program to his biweekly support group, which has continued to meet under its own direction since the trial ended. Ornish remarks, “People who are lonely, depressed, and isolated are up to 10 times more likely to get sick and die prematurely than those who feel a sense of love, connection, and community.”

Healthy Lifestyle = Fountain of Youth?

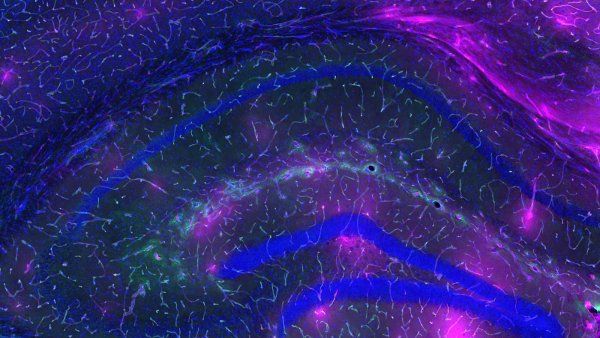

Can adhering to a healthy lifestyle do more than simply stop disease and actually add years to your life? Yes, suggests research by UCSF’s Elizabeth Blackburn, PhD, winner of a 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her co-discovery of telomeres, the protective tips on the shoestring-like chromosomes that control aging, and telomerase, the enzyme that restores telomeres as they wear down.

Elizabeth Blackburn, Nobel Prize winner and Morris Hertzstein Professor in Biology and Physiology. Photo: Thor Swift

Blackburn, a professor of biochemistry and biophysics, partnered with Ornish and Elissa Epel, PhD, postdoctoral alumna, UCSF associate professor of psychiatry, and member of the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine, to explore another angle of Carroll’s prostate cancer trial: whether a healthy lifestyle had any effect on participants’ telomere length, which corresponds to the length of human life.

The team reported that at the three-month mark, telomerase activity had increased by 30 percent in the healthy lifestyle group. This spring, Ornish will publish a subsequent five-year study showing that telomere length increased in the healthy lifestyle group but decreased in the control group.

“No other intervention, including pharmaceuticals, has been shown to make your telomeres longer,” notes Ornish. “If a healthy lifestyle could be packaged and sold like a drug, it would be a billion-dollar drug.”

Better Health at Lower Costs

When it comes to using a healthy lifestyle for clinical treatment, all diseases are on the table, as a rising number of UCSF scientists demonstrate its benefits.

“Many patients with Type 2 diabetes won’t even require medication if they can lose weight, exercise more, and therefore more efficiently use the insulin their body already has,” says Mike German, MD, resident alumnus, associate director of the UCSF Diabetes Center, and Justine K. Schreyer Endowed Chair in Diabetes Research.

Prescribing a healthy lifestyle like a drug promises to fix more than just America’s growing health issues: it also stands to have a dramatic effect on the nation’s crippling health care costs.

“Three-quarters of the $2.8 trillion we spent on health care in 2012 went to treatment for chronic diseases,” Ornish says. “If we can motivate and incentivize people to lead healthier lifestyles by reimbursing for it, we can make better health care available to many more people at much lower costs. And the only side effects are good ones.”

Medicare Reimburses for Lifestyle Changes

“Part of the myth is that lifestyle changes are only for prevention, and even then it takes years to see the benefit,” says Ornish. “But if you offer lifestyle as treatment, then both the cost savings and the clinical benefits are seen in the first year.”

Dean Ornish, a member of President Barack Obama’s Advisory Group on Prevention, Health Promotion, and Integrative and Public Health. Photo: Erik Butler

As proof, Ornish teamed up with two insurance companies to compare medical costs for patients with heart disease who chose to adopt a healthy lifestyle instead of receiving a bypass or angioplasty. Mutual of Omaha saved $30,000 per patient in the first year. Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield cut overall health care costs by 50 percent in the first year and an additional 20 to 30 percent in years two and three.

Medically, almost 80 percent of the patients safely avoided bypass surgery or angioplasty. “The blood flow to and from the heart improved in just a month, and even severely blocked arteries became measurably less blocked after a year, with more improvements after five years,” says Ornish.

The powers that be were so impressed, they were finally convinced to act: in January 2011, after 16 years of review, Medicare began covering “Dr. Ornish’s Program for Reversing Heart Disease.”

“I used to think if we just did good science, it would change medical practice,” he says. “I was wrong. Good science is important, but it’s often not sufficient. If you change reimbursement, though, you change medical practice and even medical education.”

The diet places foods in five categories. The first includes what Ornish calls the most healthful foods, like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and egg whites; the fifth contains the least healthful, such as red meat, yolks, and butter.

Watch Dean Ornish speak about the power of lifestyle changes and love at Dreamforce 2012.

To reverse heart disease and other chronic illnesses, Ornish encourages patients to adhere to a precise formula, such as at least 30 minutes of vigorous exercise and an hour of yoga every day. To prevent disease and stay healthy, he says, people have a spectrum of choices. “What matters most is your overall way of eating and living.”

“Instead of me telling you what you need to do, you tell me how much you want to change and how quickly,” Ornish says. “If you want to reduce your cholesterol level by 50 points but you’re not ready to eat a completely plants-based diet, maybe you say, for example, ‘I’ll eat a little more food from categories one through three, and less from four and five.’ If after four weeks your cholesterol comes down 30 points and you want it lower still, you can opt to do more.”

For some people, making moderate changes is effective. Others find it easier to make big changes in lifestyle. “When you change everything at the same time, you feel so much better so quickly,” Ornish explains. “It reframes the reason for changing lifestyle from fear of dying, which is not sustainable, to joy of

living, which is.”

A Prescription for Living Well

Ornish’s healthy lifestyle program, the Spectrum, consists of four main elements:

- A low-fat diet based on whole foods and plants

- Moderate exercise

- Meditation or yoga

- Love and support

The diet places foods in five categories. The first includes what Ornish calls the most healthful foods, like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and egg whites; the fifth contains the least healthful, such as red meat, yolks, and butter.

To reverse heart disease and other chronic illnesses, Ornish encourages patients to adhere to a precise formula, such as at least 30 minutes of vigorous exercise and an hour of yoga every day. To prevent disease and stay healthy, he says, people have a spectrum of choices. “What matters most is your overall way of eating and living.”

“Instead of me telling you what you need to do, you tell me how much you want to change and how quickly,” Ornish says. “If you want to reduce your cholesterol level by 50 points but you’re not ready to eat a completely plants-based diet, maybe you say, for example, ‘I’ll eat a little more food from categories one through three, and less from four and five.’ If after four weeks your cholesterol comes down 30 points and you want it lower still, you can opt to do more.”

For some people, making moderate changes is effective. Others find it easier to make big changes in lifestyle. “When you change everything at the same time, you feel so much better so quickly,” Ornish explains. “It reframes the reason for changing lifestyle from fear of dying, which is not sustainable, to joy of living, which is.”