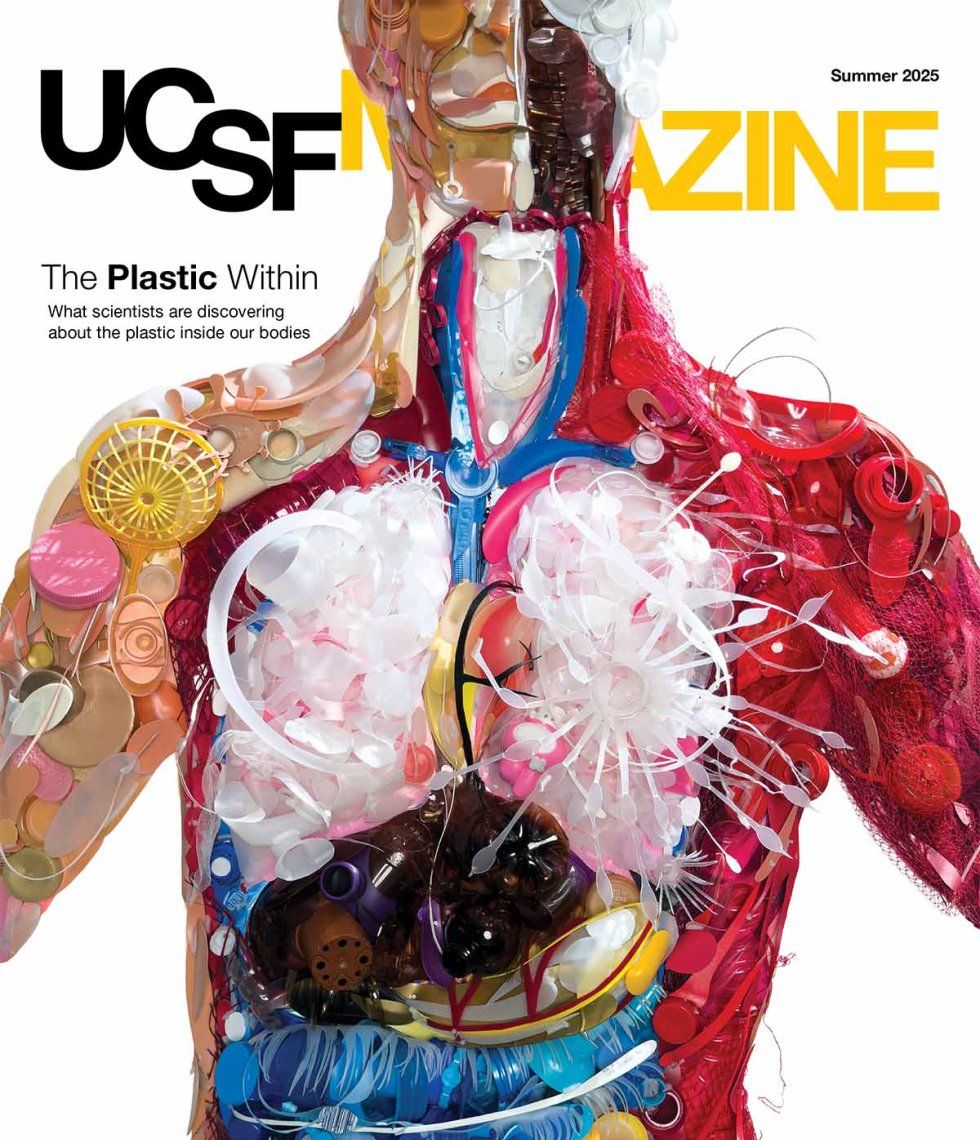

Can Music Benefit Our Brains?

Here’s how music may help flex our neurons.

We asked UCSF’s Julene Johnson, PhD, how music promotes healthy brain function. Johnson is an expert in cognitive neuroscience and music and a professor at the UCSF School of Nursing’s Institute for Health and Aging. She also plays the flute, as well as a mean kantele – a plucked string instrument from Finland.

What’s the connection between music, language, and memory?

When I was a PhD student at the University of Texas at Dallas, I worked with the local Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center studying how people with that condition retain musical memory. Sometimes, older adults can remember how to play music, read music, or sing better than they can speak. I learned that the brain’s neural networks supporting music processing and production are slightly different from those supporting language production and understanding.

We know that music can stimulate language networks. For example, the melody in poetry or song lyrics can serve as a cue to help produce speech in people who have experienced a stroke. Research suggests that during speech rehabilitation, different parts of the brain can help take over language production.

How does musical improvisation boost brain health?

When you’re improvising, you have to let go and be flexible. So some of the control and planning parts of the brain actually deactivate, and the more creative parts of the brain activate.

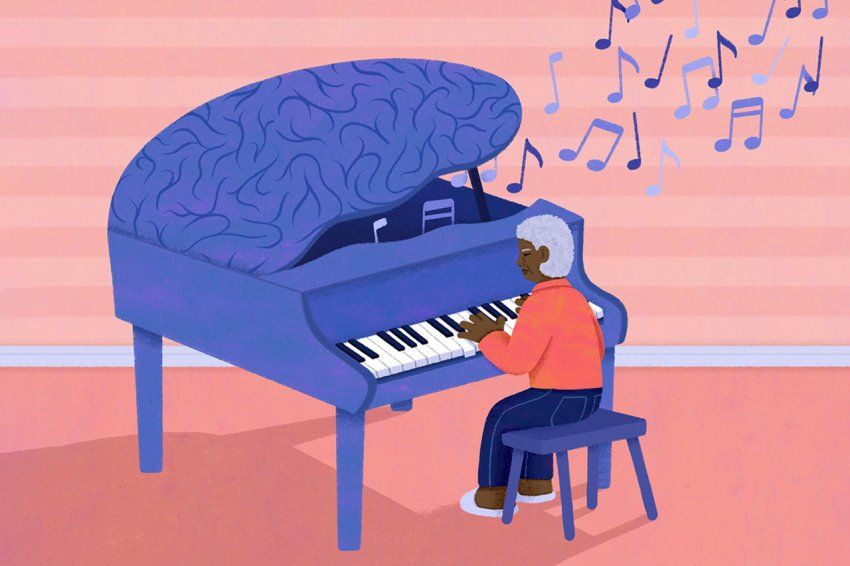

I’m collaborating with Charles Limb – a neuroscientist and the chief of otology, neurotology, and skull base surgery at UCSF – to study how piano improvisation training affects older adults. Though challenging, such training offers an accessible way to explore music, helping people practice cognitive flexibility while also learning fun and interesting new skills. Ultimately, we hope it encourages older adults to keep pursuing challenging cognitive activities throughout their lives. Music is not only pleasing and beautiful, but it also puts the brain to work.

Why the piano?

Learning basic piano skills is relatively easy, allowing study participants to improvise more quickly than they might on other instruments. Our participants are beginners with less than three years of piano experience. Many don’t know how to read music, so we encourage them to learn by ear and experiment with piano improvisation.

Previously, I conducted a large clinical trial, with roughly 400 older adults living in San Francisco, on the benefits of singing in a choir. We found that group singing can reduce people’s loneliness and significantly increase their interest in life. However, participants did not experience any cognitive changes. The benefits were social and psychosocial. On the other hand, piano training is linked to improved brain function, especially in problem-solving and attention.

How does playing music affect our brains differently from listening to music?

I often make the analogy of playing football versus watching it on television. Both are interesting, but the folks playing football are more committed physically, cognitively, and emotionally than those just watching it on TV. Also, we know that the more meaningful music is to someone, the more mentally engaged they’ll be. For example, in people living with Alzheimer’s, musical memory is often preserved even in the later stages of the disease.

Is listening to Beethoven more stimulating than listening to the Rolling Stones?

I know people who relax to rock music! The idea that there’s a relaxing type of music is just not true. It comes down to how someone experiences music – what they find calming or energizing. Musical tastes are very personal. There’s not some magical composition that has health effects. Music interacts with individuals’ life histories, their experiences growing up, and what’s meaningful to them.

How does music help people living with dementia and their families?

It can be a source of deep meaning and identity and can even help reinforce relationships and social connections. Integrating music into their everyday life brings people joy, facilitates relaxation, promotes bonding, and encourages singing and dancing. I am working with the AARP’s Brain Health Action Coalition to promote music throughout the dementia journey.

Theresa Allison, a geriatrician at UCSF, is studying the effects of music in home settings for people living with dementia and their care partners. She has found that when older adults listen to music that is meaningful to them, they enjoy an improved quality of life.

Can music be used to treat other cognitive challenges?

Yes, just as medications are prescribed for specific symptoms, music can be tailored to address different needs. For example, if a patient comes to our clinic and reports feeling lonely, their doctor might prescribe group singing. If a patient is concerned about their cognitive abilities, their doctor might recommend piano training.

So, does music have other health benefits beyond the brain?

Absolutely. If I had a crystal ball, I’d love to see music-based interventions in many different areas of health care. There’s a wonderful story about an opera singer living with cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder that can make breathing difficult. She started a nonprofit called Breathe Bravely, which helps others with cystic fibrosis discover the transformative connection between singing and breathing. It’s really inspiring, and I’d like to see more of that in the future. I would also like to see music being used to help heal communities that have experienced trauma, whether from violence or chronic underinvestment.