Lillian Carson was 11 when the fear struck. She had always been a sensitive child who tuned in to the feelings of animals and other people. But after her dad was diagnosed with cancer, she spiraled into worry and sleeplessness. “I would be up at night, huddled in the corner with my dog, and my sheets over my head, thinking someone was going to break through my window and get me,” she remembers.

Her parents took her to therapy, which eased her anxiety for a while. “It was still prevalent in my life, but it wasn’t something that stopped me from being a kid,” Lillian, now 16, says. “Then the pandemic came, and that all changed pretty rapidly.”

Lillian was about to graduate from middle school when the world went into lockdown. By then, her dad’s cancer was in remission. She was dancing hip-hop and going to plays and art museums with her family. She had just experienced “some bad friend-group stuff” and was looking forward to high school. “I thought it would be a fresh slate for me,” she says.

Instead, she found herself alone in her room most days, hunched over her laptop or on her phone. “I had absolutely no connections, no friends to talk to, no one really to hang out with,” she says. “There was just this very strong sense of loneliness.”

There was just this very strong sense of loneliness.”

The fear returned with a vengeance. She stopped sleeping again. A mild chest injury morphed into a condition called amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome, which can be brought on by psychological stress. “She had these bouts of intractable pain,” recalls Lillian’s mom, Beryle Chandler-Carson. “We were going to the ER in the middle of the night and seeing dozens of different medical specialists.”

Meanwhile, getting a mental health appointment proved next to impossible. “There was nobody who could get you in unless it was online,” Lillian says. And online therapy, in her opinion, was a bust. “It feels really hard to be yourself and be connected when it’s on a screen,” she explains.

Lillian Carson participated in a UCSF study that examined how a new intervention for depression and anxiety rewires teen brains. “That was the coolest thing I experienced in the study, getting to see my own brain,” says Lillian. Video: Walter Zarnowitz | Watch and share on Youtube

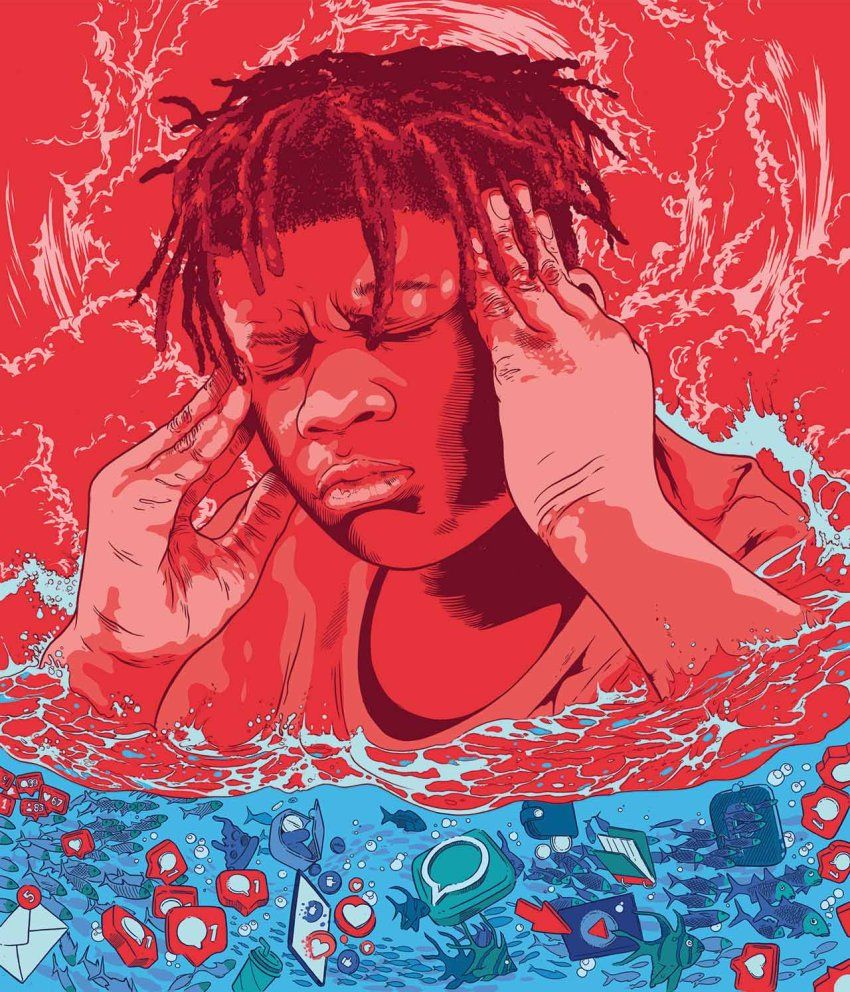

Lillian is not alone in her suffering. Even before COVID-19, teen mental distress was spreading at an alarming clip. In 2011, 1 in 4 high schoolers felt persistently sad or hopeless, according to survey data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. By 2019, the ratio had jumped to 1 in 3. In 2021, at the height of the pandemic, almost half of teens reported such feelings. Over the same decade, emergency room visits by children and young adults for anxiety, mood and eating disorders, and incidents of self-harm climbed sharply. Suicide rates soared.

“It’s a problem that’s been at a crisis level for years, and COVID just threw fuel on the fire,” says Tony Yang, MD, PhD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and neuroscientist at UC San Francisco. The tide of adolescent anguish spans geographic, economic, and racial and ethnic divides. And its causes are multifaceted and still poorly understood. Should we blame the rise of social media and cyberbullying? The decline in sleep, exercise, and good nutrition? The earlier onset of puberty? The political and climatic turmoil that has beset the world?

Making matters worse, most teens who need help can’t get it. “There just aren’t enough therapists who are trained to handle the huge demand of patients,” Yang says. In California, more than half of counties have as few as one child and adolescent psychiatrist for every 100,000 children, and almost a third of counties have none. Even in San Francisco County, where youth mental health specialists are relatively plentiful, waitlists for therapy can be as long as a year.

In search of a solution, Yang turned to a resource that the field of psychiatry had long overlooked: the teenage brain. He was one of the first experts to study the underlying neurobiology of teen depression by imaging neural activity and connections. His research has helped uncover new insights into the condition and inspired an intervention, tailored for teens like Lillian, called Training for Awareness, Resilience, and Action (TARA).

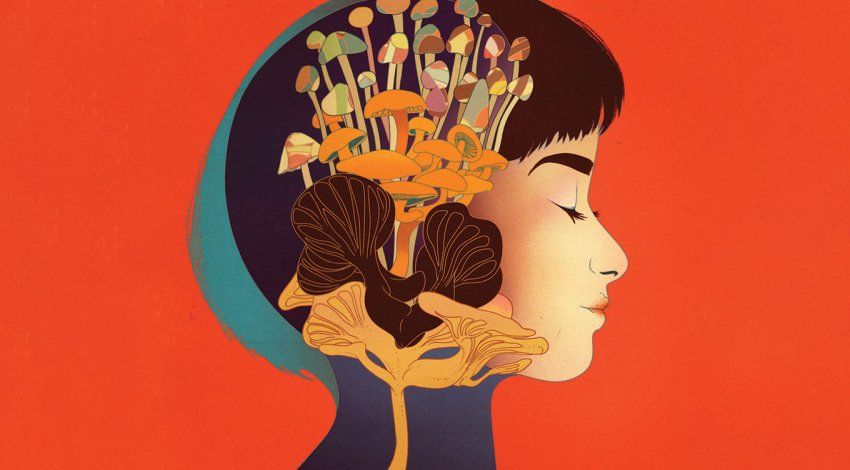

The 12-week program – developed by Yang’s former fellow Eva Henje, MD, PhD – draws from mindfulness meditation and yoga as well as more traditional forms of psychotherapy. Mindfulness practices, which originated in the Buddhist and Hindu traditions, cultivate the ability to observe experiences in the present moment without reaction or judgment. Mounting evidence shows that these practices can alleviate depression and anxiety and reduce relapses in adults. Yang is now leading studies of TARA with UCSF’s Olga Tymofiyeva, PhD, to see whether the intervention can similarly benefit teens who can’t get or may not need advanced professional care.

“The advantage of TARA is that it doesn’t require a clinical psychology degree to deliver it,” Yang says. “High school teachers and counselors could be trained to do it.”

Of Puberty and Plasticity

Adolescence is a tumultuous time for the human brain. Puberty ushers in a period of profuse neural rewiring that is surpassed in scale only during the first three years of life. Well-worn tracks between neurons strengthen, while idle paths are pruned away, allowing different parts of the brain to become more interconnected and specialized.

But this remodeling is not uniform. The most dramatic and rapid changes occur in the limbic system and other structures that drive emotions and respond to reward, novelty, and threat. By contrast, the prefrontal cortex – which carries out executive functions like reasoning, planning, and social interaction – matures slowly, until well into a person’s 20s.

The roughly 10-year gap between the ripening of these two brain areas primes teens to act impulsively, take risks, and seek out the approval of peers. “It’s why, when you’re a teenager, you have a harder time exercising good judgement,” Yang says. It’s also why teens are particularly vulnerable to mood disorders like depression.

Although depression in teenagers shares many characteristics with adult depression, there are important differences. Most adults with depression are despondent; they shut down and turn inward. Depressed teens can be gloomy, too. But they’re also often irritable, and they don’t always say that they’re sad. They might become restless, deliberately injure themselves, get into arguments, abuse alcohol or drugs, or eat or sleep more or less than usual.

Research by Yang and others has begun to sketch a picture of how this affliction takes root in a teenage brain. In some teens, a combination of genetics, childhood trauma, and increased social and academic pressure may cause the brain’s emotion circuitry to become hyperactive, magnifying feelings of fear or chagrin. At the same time, the reward circuitry that helps teens feel motivated and take pleasure in achievement is understimulated. All of this can produce weak or maladaptive links to the managerial prefrontal cortex, making it even harder for a teen to control strong negative thoughts or emotions, strive for goals, and form healthy relationships.

“Depression impacts a teen at the critical stage in their life, when they’re developing social skills,” Yang says. “If they’re not able to do that, it places them at a huge disadvantage. They’re at much higher risk for substance-use disorders, for suicide, for failing academically, and later on in life, for losing jobs and getting divorced.” People who go through a bout of depression during childhood also tend to have recurring episodes as adults. “They are more likely to suffer from longer, more frequent, and more severe depressive episodes each time,” Yang says. “The depression becomes more and more entrenched and more and more difficult to treat.”

The good news, though, is that the same malleability, or plasticity, that makes the teenage brain susceptible to mental illness also makes adolescence an “ideal time to intervene,” Yang says. The most effective treatments for teen depression – those backed by the most scientific evidence – include the antidepressant medications fluoxetine (Prozac), escitalopram (Lexapro), and sertraline (Zoloft) and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), which teaches people to manage their feelings by changing the way they think and behave. These are what clinicians consider first-line treatments.

But they’re far from a sure bet. “It depends on the treatment, but on average, we can get about half of our patients half-better,” Yang says.

“There’s more and more data questioning how helpful antidepressants really are for adolescents,” adds UCSF’s Lisa Fortuna, MD, MPH, the Carol Cochran Schaffner Professor of Mental Health and chief of psychiatry at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. “They’re probably most helpful in combination with talk therapy for kids with more severe symptoms. For kids with mild symptoms, the role of antidepressants is less clear.”

CBT can help with all levels of depression. But given on its own, it seems to work less reliably in teens than in adults, possibly because it focuses on using the prefrontal cortex to regulate emotion – something the adolescent brain is still mastering. “It’s funny,” Fortuna says. “When I would talk to kids about doing cognitive therapy, they would say, ‘What the hell? You’re asking me to think. I can’t do that when I’m in the middle of some horrible stress or argument.’”

Fortuna often sees children dealing with traumas related to poverty, immigration, abuse, and addiction. Almost 20 years ago, she began giving her patients mindfulness exercises, which seemed to help them learn and use cognitive strategies. “Mindfulness can help young people cut through the static that trauma sometimes creates in their minds so that they can see things more clearly and make decisions for their own self-care,” Fortuna says. (She later developed these insights into a program called Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for adolescents with trauma and substance-abuse disorders, or MBCT-Dual.)

Yang had come to a similar conclusion: To be most effective, an intervention for teen depression should take a “bottom-up” approach – calming the overactive limbic system – in addition to tackling the “top-down” faculties of the prefrontal cortex. In 2013, he decided it was time to put this theory to the test.

Brain Boot Camp

That year, Henje arrived in Yang’s lab as a postdoctoral fellow. Early in her career as a psychiatrist, she had worked in an emergency psychiatric ward in Stockholm and become disillusioned with the standard of care there. “Teenagers would come in who were suicidal, and I was expected to put them on all these drugs,” Henje, now at Sweden’s Umeå University, recalls. “I did, and then a few weeks later, they would come back and were more suicidal and more anxious. It felt unethical to me.”

She opened a private practice offering nonpharmacological therapies and founded a yoga institute, where she taught mindfulness and yoga to address stress and depression. Eventually, she grew curious about how these disciplines alter the body and brain and went on to earn a PhD in clinical neuroscience from the Osher Center for Integrative Health at Sweden’s renowned Karolinska Institute.

Since 1998, the Bernard Osher Foundation has established eleven such centers around the globe; the first one was at UCSF. The Osher Centers treat patients using a combination of conventional medicine and complementary remedies, including herbs, acupuncture, massage, yoga, and meditation. They also educate physicians and the public about these techniques and conduct research on their effects.

For Henje, UCSF’s Osher Center was a “mecca for mind-body medicine.” In Yang’s lab, she combined her mindfulness and psychiatric expertise with his neuroscience to create what would become TARA, and the Osher Center pitched in to fund a pilot study in 26 teens. By 2015, the team had recruited their first volunteers.

Coming together with other teens and talking about your feelings and concerns is the first step in creating the future you want.”

The teens met in groups once a week for three months, sitting in a circle on yoga mats. The training consisted of four modules. Each module lasted three weeks and targeted different brain regions, starting with the emotional limbic system and working up to areas governing attention and cognition. (Throughout TARA, participants also got lessons in nutrition, stress, and sleep.)

During the first module, the teens learned yoga-based movements and simple breathing exercises. One exercise, called square breathing, involves holding the breath between inhalations and exhalations. Another, called ocean breathing, uses a constriction of the throat to make a sound like a wave.

It’s thought that such slow and deep breathing induces a sense of calm by engaging the parasympathetic nervous system. This network of nerves relaxes the body – steadying the heart rate, unclenching the muscles, and lowering blood pressure – after moments of stress or danger. Henje and Yang hypothesized that the TARA exercises could quiet the amygdala, a limbic structure that triggers the so-called “fight or flight” response and is especially overactive in teens with depression. This, in turn, could promote healthy connections to the anterior cingulate cortex, which routes communication between the limbic and cognitive centers and which seems to be miswired in depressed teens.

The second TARA module emphasized paying attention to what’s going on inside the body. The teens lay down on their mats and slowly scanned their body in their mind’s eye, from the top of their head to their toes, noticing what sensations arose. Such exercises call upon the insula – the seat of awareness and interoception, or the ability to perceive one’s internal state. Tuning in to the present moment also distracts the mind from worrying: When the insula is preoccupied, the brain has fewer cognitive resources to devote to tasks like negative self-talk and rumination.

In the third module, the teens finally put to work the thinking part of their brain, the prefrontal cortex. They practiced recognizing and naming emotions. They imagined their thoughts and feelings cascading before them, like a waterfall, and watched their anger, anxiety, or boredom tumble down the rapids without themselves being pulled into the turmoil. They discussed how different parts of themselves can think conflicting things – like how one part might wish to die while another part really wants to make the soccer team.

The fourth and last module – meant to strengthen reward structures like the striatum and orbitofrontal cortex – was all about action. The teens shared what they cared about most and created goals that aligned with those values. They dreamed about their future lives and all they would accomplish. Sometimes the discussions veered into existential angst: If going to school means I’ll have a boring job like my parents, what’s the point? If the planet is destroyed, what future do I have?

“These are appropriate questions,” Henje says. “Teenagers often feel unheard and dismissed by my generation, which creates a sense of hopelessness or anxiety. I want to validate their experience and say to them, ‘There’s nothing wrong with you. So much in the world is overwhelming right now, and you are not alone. Coming together with other teens and talking about your feelings and concerns is the first step in creating the future you want.’”

How to Train Your Brain

UCSF scientists are testing an intervention for teen depression called Training for Awareness, Resilience, and Action (TARA) that’s based on emerging insights into the teenage brain. The 12-week program consists of four modules, each designed to target different brain areas that may be miswired in depressed teens.

Click on the numbers to learn more.

Brain map concept credit: Eva Henje, Olga Tymofiyeva, and Tony Yang

Raising Resilience

The pilot study, published in 2017, showed that TARA significantly improved symptoms of depression and anxiety and led to a larger trial funded by the National Institutes of Health that is now underway. Its first phase enrolled 100 healthy teens who, like Lillian, may have had depressive tendencies but no official diagnosis. The main aim was to see how TARA rewired their brains, says Tymofiyeva, an expert in magnetic resonance imaging who is co-leading the new study. (She is also a certified hypnotherapist and an author of young adult fiction.)

Yang and Tymofiyeva launched the trial, called Brain Change, in 2019. But when COVID hit, their team had to adapt TARA for Zoom and restart in 2021. Half the teens took the TARA course online; the other half served as controls. All of the teens’ brains were scanned before and after the sessions to compare the outcomes.

“That was the coolest thing I experienced in the study, getting to see my own brain,” says Lillian, who was assigned to the TARA group. She particularly liked the breathing exercises and body scans, which she still does sometimes when she’s frustrated or anxious. “I’ll be in a disagreement with someone or just feel not great, and I’ll do square breathing or a body scan for five minutes,” she says. “It makes me feel more grounded and able to look at other people’s perspectives.”

She says she also has become more aware of how her choices, such as what she eats or what songs she listens to, affect her mood. “If I’m feeling down, I’m not going to start playing demeaning music about ‘effing bitches’ and stuff like that.” She still regularly struggles with anxiety, she says, “but I have a lot better coping mechanisms to deal with it.”

Lillian also sees a therapist now and has tried other treatment programs, her mom points out, so it’s hard to know how much of an impact TARA has had. But she has noticed that Lillian seems to be more motivated to use some of its tools after practicing them with a group of peers.

“Other teenagers were doing it, so it made it a little less uncool,” Lillian agrees, although she wishes she could have met her fellow participants offline. “I didn’t get to form real connections with them,” she says.

Yang and Tymofiyeva are now analyzing the data from the first Brain Change cohort and, according to preliminary reports, have shown that the teens’ brains indeed have changed – particularly in areas associated with emotion, awareness, and reward. Encouraged by these findings, the researchers have begun recruiting a new cohort of 120 teens with elevated depression. They expect to see even greater therapeutic benefits and neural rewiring in this group than in the healthy volunteers.

Experts are optimistic that programs like TARA – if proven effective and made widely accessible online or in schools – will help slow or even reverse the steep decline in mental health among adolescents. But early interventions are only part of the solution. There will always be teens who need more specialized mental health care, and many of them will turn to pediatricians, who often are the only providers with availability.

“The need is so big that pediatricians are now regularly seeing really tough cases, and of course they are overwhelmed,” says Anne Glowinski, MD, the Robert Porter Distinguished Professor and division chief of child and adolescent psychiatry at UCSF. Most family doctors, she notes, lack the training or resources to manage psychiatric care. “We need to move some of that care to pediatrics to grow our workforce, but it needs to be done thoughtfully and deliberately so that providers feel knowledgeable and supported and not dumped on.” (Pediatricians in California can find resources and consult with psychiatrists through UCSF’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Portal.)

An Avalanche of Anguish

Feelings of despair and suicidal thoughts and behaviors rose significantly among high school students over the past decade, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Persistently felt sad or hopeless

Seriously considered suicide

Made a suicide plan

Attempted suicide

Graph source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Hospitals will also need to vastly expand their capacity to care for kids who are suicidal or in danger of harming themselves or others. The younger, sicker, and poorer a child is, Glowinski notes, the fewer options they have; families frequently wait hours or even days in emergency rooms for open beds.

In San Francisco, there are zero beds dedicated to mentally ill children and around 18 to adolescents, located at St. Mary’s Medical Center. A planned youth psychiatric center at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital will add another 12 beds for adolescents. And at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, which opened an outpatient center for youth mental health services in May, plans for a new hospital building include an inpatient mental health wing with as many as 24 beds for young children and teens.

Coming of age today means facing a future that looks increasingly precarious. As the editors of The Lancet recently wrote, a teen of Lillian’s age has “gone through the great recession and the subsequent austerity measures, a pandemic with disrupted schooling and social isolation, a cost-of-living crisis, war in Europe, and a world coming to terms with the magnitude of climate change.” Our children will confront challenges we never imagined. We can’t shield them from adversity, but we can help them build the resilience they need to face it and thrive.