Cracking the Coronavirus Gender Mystery

Why does COVID-19 seem to take a greater toll on men than women? Stem-cell biologist Faranak Fattahi has found a clue.

Faranak Fattahi, captured via FaceTime in her lab in UCSF’s stem cell building on May 15 at 11 a.m. by photographer Steve Babuljak

Faranak Fattahi, PhD, has seen the numbers: In China, 1.7 times as many men as women have died from COVID-19. In Italy, 1.8 times as many. In Thailand, almost 3 times as many. She has read the speculations: Maybe it’s because men have weaker immune responses. Maybe it’s because they smoke more or don’t wear masks as diligently. Maybe it’s genetics.

But Fattahi, a UCSF Sandler Fellow, has her own hypothesis – and data to back it up. Like hundreds of scientists across UCSF, she has repurposed her research laboratory to investigate the coronavirus now ravaging the world. She shares what she’s learned about the COVID-19 gender gap and describes how her team identified FDA-approved drugs that show promise for preventing the disease.

What did you do when San Francisco’s shelter-in-place orders shut down labs not involved in COVID-19 research?

My lab uses stem cells to understand the mechanisms of disease and come up with treatments. Basically we model, inside a laboratory dish, the biological processes that are happening inside a patient.

The Fattahi lab meets via Zoom.

When the pandemic hit, we first thought, “Oh, there’s nothing we can do; we’re totally helpless.” But gradually we realized, “There’s this virus out there that people don’t know anything about. COVID-19 is a completely new disease. We don’t understand how it happens, how it affects different organs in the body, or how to treat it. So let’s do some experiments.”

Where did you start?

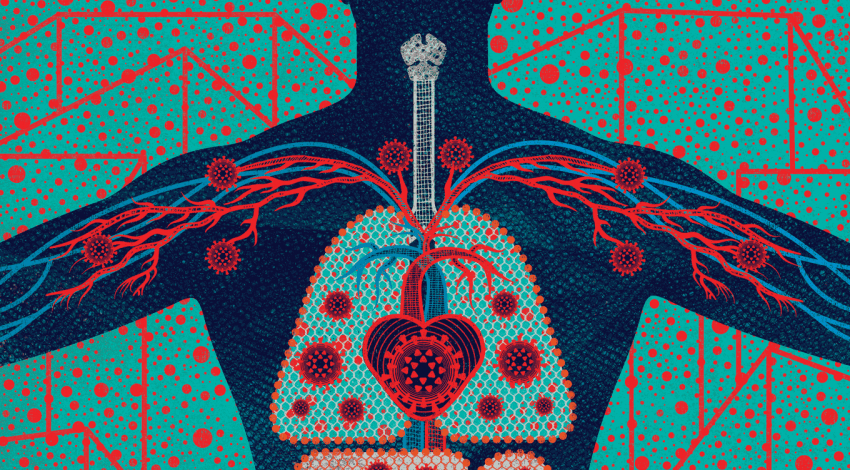

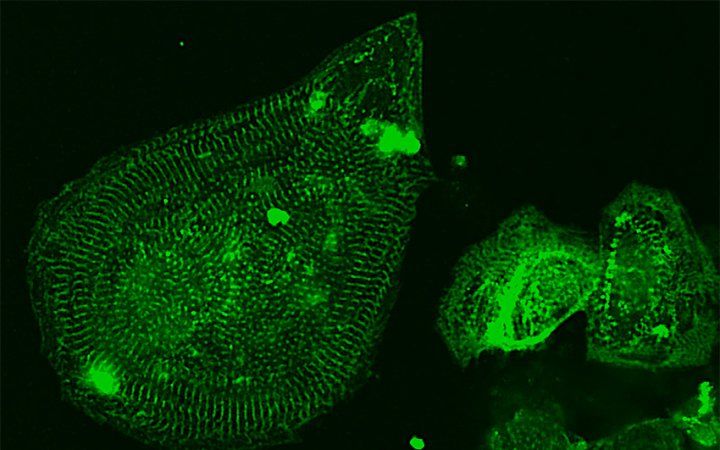

We knew that COVID-19 doesn’t just affect the lungs. It also affects the heart, as well as other organs. In my lab, we were studying how cardiomyocytes – heart cells – interact with the nervous system. We decided to repurpose these cells to understand how the coronavirus enters and infects them – and how to prevent that viral entry from happening.

We focused on a specific protein called the ACE2 receptor. It sits on the surface of many cells in your body – not just heart cells, but also lung cells, intestinal cells, kidney cells, and others. This receptor plays a very important role in regulating blood pressure, but it also enables the virus to get inside your cells.

Are you saying the coronavirus uses the ACE2 receptor to essentially hijack cells in order to make more copies of itself?

Exactly. You can think of the ACE2 receptor like a docking site on a cell. When a virus lands on it, it initiates a molecular process that brings the virus inside the cell.

Our idea was: Can we figure out how to reduce the number of ACE2 receptors on our heart cells and thus prevent the virus from entering them? We tested around 1,500 FDA-approved drug compounds on these heart cells, and we found that five of these compounds did just that – they reduced the number of ACE2 receptors on the cells’ surfaces.

And that means the virus has fewer opportunities to enter the cells?

Yes. The fewer ACE2 receptors, the less risk of infection – that’s the idea. The most effective drug that we found is called dutasteride. And there’s a similar drug called finasteride. These drugs are typically prescribed to treat an enlarged prostate; they inhibit androgens, or male sex hormones.

That really caught our attention, because we knew that men are more susceptible to severe cases of COVID-19. We also knew that kids are more protected. It’s possible that people who have higher levels of androgens like testosterone – namely, adult men – are more likely to get severely sick from a coronavirus infection because their cells have more ACE2 receptors to let the virus in.

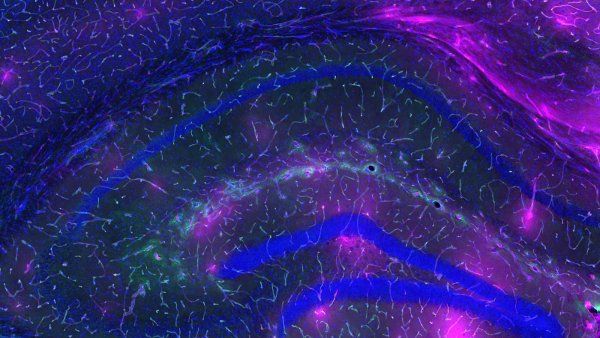

Fattahi’s team uses heart cells (above) grown from human stem cells to test drugs for COVID-19. Image: Zaniar Ghazizadeh

Is there other evidence for that hypothesis?

We also looked at patient data. We worked with collaborators at Yale New Haven Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, who helped us analyze anonymized records from about 2,000 COVID-positive patients. We found that patients with elevated levels of testosterone had a higher chance of developing cardiac complications during a COVID-19 infection. So there does seem to be a link between androgens and the severity of COVID-19.

However, it’s important to remember that this is still just our hypothesis. We submitted our observations as a preprint to bioRxiv; it’s not a peer-reviewed journal, but we think it’s worth publishing what we’ve found quickly so other scientists can follow up.

What’s next?

We need to understand a lot more about these androgen-inhibiting drugs. The good news is that they’re relatively safe. But we still have a lot of questions to answer: Are these drugs really effective against COVID-19 in human patients? At what stage of the disease should they be given? At what dose?

Then maybe the next step would be a clinical trial.

When do you find time to sleep?

[She laughs.] It’s been pretty intense. For a few weeks, I would go in to the lab late at night to avoid rush hour and work long hours doing the drug screens. I did most of those wet-lab experiments myself because I didn’t want to put my lab members at risk. But they did a ton of work analyzing results from the drug screens and other data. It was a major team effort.

Researchers are coming together to look for a solution. We’re eventually going to find it.”

You grew up in Iran. Is your family still there?

They’re all in Iran. My siblings all work in health care. I’ve been in touch with them, asking how things are going, trying to anticipate what’s going to happen here. Iran was two or three weeks ahead of the U.S. in terms of the original COVID-19 surge. Now the government there is reopening schools and parts of cities and some little towns. That makes me hopeful there will soon be changes here as well.

When was the last time you saw your family?

I came to the U.S. in 2011 for my PhD. I haven’t been back to Iran since. Iranian citizens studying in the U.S. are given a single-entry visa; if we leave, we won’t be able to automatically come back. The last time I saw my parents was when they came to visit me in the U.S. a few years ago, before the 2017 travel ban.

What about the coronavirus pandemic worries you?

My fiancé is a resident in internal medicine. He has been taking care of COVID patients. He tells me these horrifying stories about super-young people being intubated for weeks. Even if they recover, they could have long-term health problems – with their lungs, their kidneys, their heart. Who knows what’s going to happen?

What gives you hope?

Since the beginning of the pandemic, so many labs have come together to share ideas and tools. We’re working nonstop day and night to find a way out of this crisis. And that’s just at UCSF. All around the world, researchers are coming together to look for a solution. We’re eventually going to find it.

More from this Series

With campuses closed, Joseph Kidane serves with hundreds of his fellow medical students in a volunteer crisis workforce.