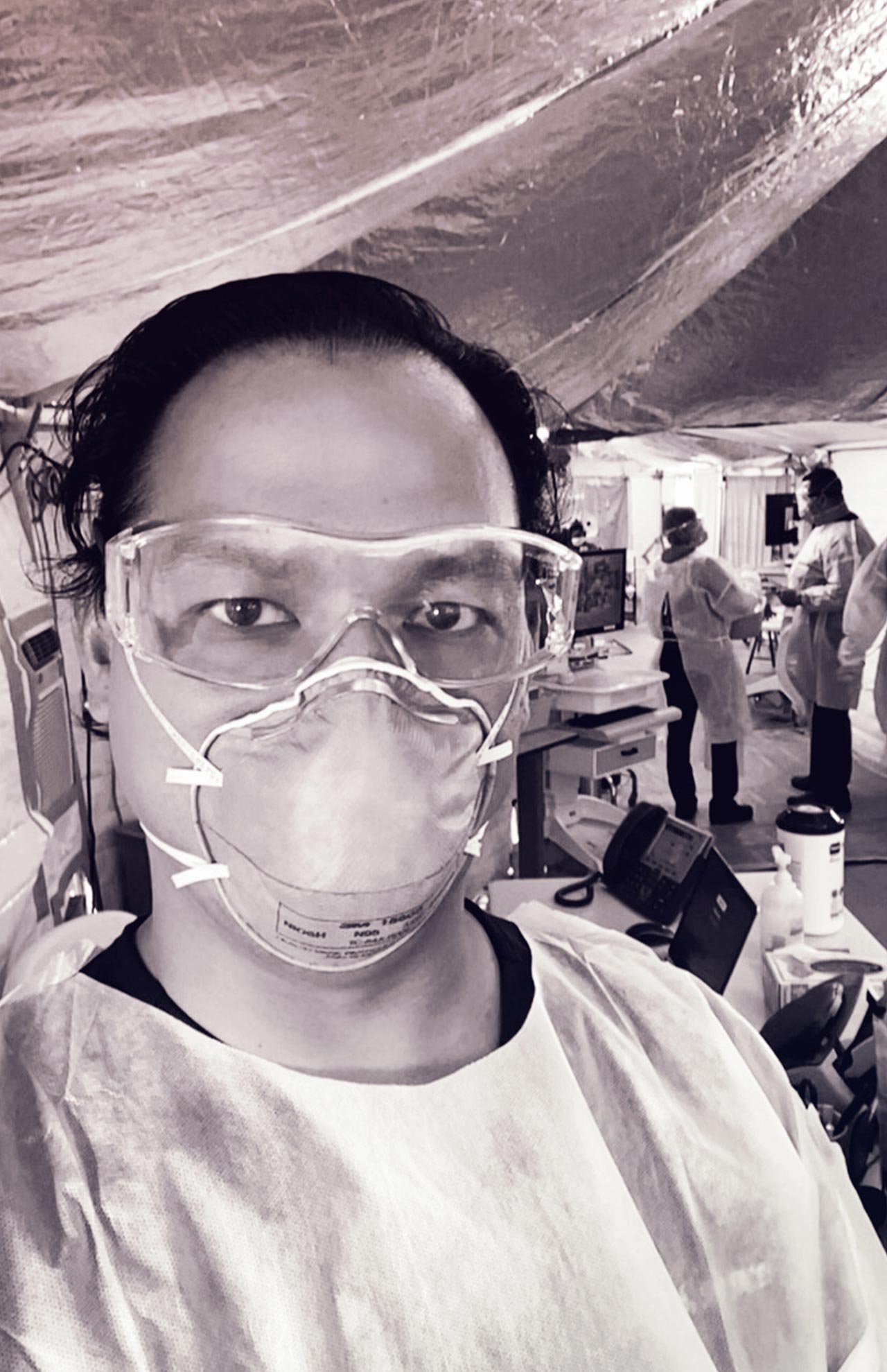

ER: The Hospital’s First Line of Defense

At the UCSF Medical Center’s dangerous-entry portal, Emergency Medicine Chief Maria Raven looks out for safety.

Maria Raven captured via FaceTime in the UCSF Helen Diller Medical Center Emergency Department’s crash room on June 12 at 9:49 a.m. by photographer Steve Babuljak

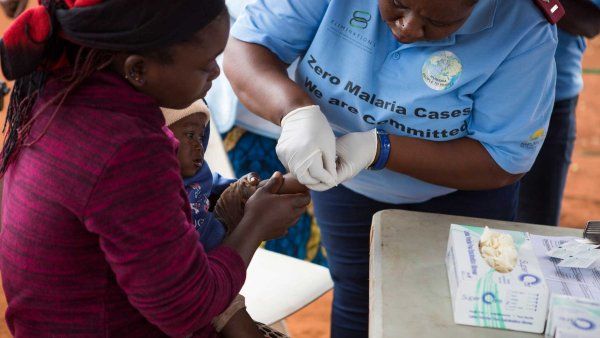

In mid-March, as the novel coronavirus proliferated in California, UCSF Hellen Diller Medical Center at Parnassus Heights erected military-grade shelters where members of the Emergency Department could isolate suspected COVID-19 patients for triage before they even entered the hospital. It was just one of countless initiatives led by UCSF’s chief of emergency medicine, Maria Raven, MD, MPH.

In the days leading up to that tipping point, Raven’s decision-making had to be nimble and responsive, as growing numbers of suspected – and unsuspected – COVID-positive people began arriving in the Emergency Department.

Why is it so difficult to diagnose COVID-19?

Everyone has different symptoms. Some patients have obvious symptoms, like severe respiratory issues. But one woman came in with just abdominal pain and vomiting and had a big workup for potential gallbladder disease. Then the CAT scan of her abdomen showed the lower part of her lungs, and the radiologists said, “This looks like classic COVID.” It turned out she had a bit of chest pain and a cough that she just hadn’t told us about because her main concern was the gastrointestinal symptoms. Her gallbladder was fine. But she had COVID.

Given the diagnostic challenges, how has the Emergency Department handled safety?

Maria Raven (center) speaks with nurse Joy Rios (right) inside an accelerated care unit on March 6, 2020. The unit provides a negative pressure environment to house patients with respiratory symptoms. Photo: Noah Berger

We’ve had many iterations of personal protective equipment, or PPE, but we’ve always been a bit ahead of the curve.

Before the shelters went up, we had patients in hallways or being rolled in by paramedics, and they could have been spreading respiratory droplets everywhere, right? So we made it so every single person, even our clerks, wore a mask and eye protection at all times.

Very early on, we also prohibited visitors in the Emergency Department. Probably in mid-March, I was checking on everything and saw an elderly family member of a patient walking through our hallways, and I thought, Wait, we can’t have elderly visitors in Emergency – they’re at risk for getting this.

I remember just saying, “OK, make some signs, put them up. Here’s what they’re going to say. Laminate them.”

And then we did it more formally – UCSF actually made really nice signs for us. A week later, when the San Francisco Health Department ordered hospitals to close to visitors, the incident-command team was like, “Can we see your signage?”

But we just did it. It was the right thing to do.

So you went rogue?

Well, in reality what we did was take action when we felt it was needed, without asking permission – sort of an “act-now, ask-later” situation.

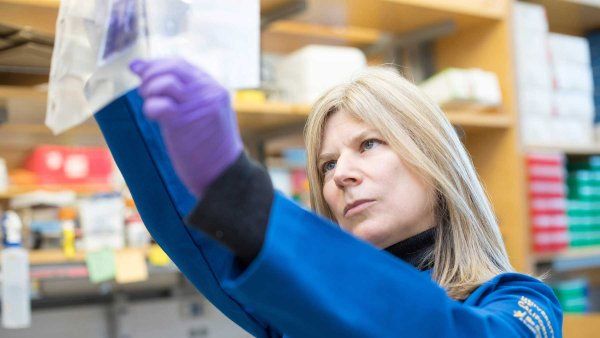

Maria Raven is also an associate professor of emergency medicine at UCSF, where she studies how to improve care delivery for patients with complex medical and social needs. Photo: Noah Berger

That makes sense. You are that first point of contact.

I feel very protective of our faculty and all of our providers and staff because we really are the front line for the hospital.

By the time someone is admitted, the staff largely knows if they have COVID, or at least if they’re highly suspected for COVID, and they go into an isolation room. Before providers enter that room, they don protective gear to avoid getting or spreading the infection.

But when people come into the ED, they’re completely undifferentiated – we don’t know if they have the virus. You could be coming to us with a stroke, or we could be intubating you for something else, and yet you could have COVID.

That puts us in a very high-risk situation – basically, our entire ED is like the inside of an isolation room. So just before the shelters went up, we made a decision (this was another time we didn’t ask permission) to have all of our providers in full airborne gear – gloves, N95 masks, and eye protection – for their entire shift. Patients also wear masks.

Has testing improved safety?

Early on, we had to take many, many steps to even get a test. We had to call infection control, who would call the Department of Public Health, who would call the CDC. We had a lot of possible cases, but we could only test people who were sick enough to be hospitalized.

We had to come up with really clear instructions for people we released who might have COVID – they needed to self-quarantine. It was confusing for patients and upsetting for providers. Now that we have so much more control over the testing, since UCSF really developed its testing capacity, it feels much better. But at first it was really, really difficult.

What else has helped?

We’ve been vigilant about PPE, and the prevalence of COVID in the Bay Area has been so low that we have had only one faculty member test positive. Now [early May] it feels like things are much more under control. We’ve had so much preparation in the Emergency Department.

Like what?

A couple of our faculty members worked with some Exploratorium scientists, and they developed face shields for us and an intubation box – a clear Lucite box you put over a patient’s head so it protects you from all the aerosols that you put your hands through when you intubate them.

And we’ve come up with some cool ways to give people breathing support that don’t require a ventilator. We also have all of our information about COVID on one platform, which everyone has on their mobile phones.

You spend a lot of time caring for others – faculty, staff, patients. How are you doing? Do any especially tough days still linger?

One of our faculty members was one of the first people in the med center to test positive. That was a bad day. It was the first day after we got our shelters up, and everything was moving, moving, moving so quickly; we were working so many hours. It was the first day I actually slowed down. That was tough – to really stop and think, OK, this is real.

More from this Series

UCSF Fresno physician Kenny Banh, MD, fights both COVID-19 and inequity in the San Joaquin Valley.