Can This Controversial New Drug Curb Alzheimer’s Disease?

Neurologist Gil Rabinovici digs into the debate over aducanumab

Published August 13, 2021; updated December 15, 2021

In June, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug aducanumab (marketed as Aduhelm) for treating Alzheimer’s disease, reactions were mixed. Some experts considered the decision a breakthrough moment for a field that hasn’t offered a new therapy in more than 20 years. Others – including three members of the FDA’s own advisory committee, who resigned in protest – called it a regulatory failure.

UCSF neurologist Gil Rabinovici, MD, the Fein and Landrith Distinguished Professor of Memory and Aging, explains the controversy and shares why he thinks Alzheimer’s care is entering a new era “regardless of whether aducanumab proves to be a blockbuster or a bust.”

Gil Rabinovici, MD,

Professor of Neurology

How does aducanumab treat Alzheimer’s?

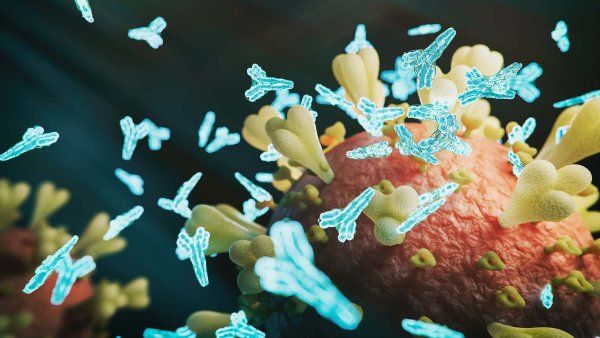

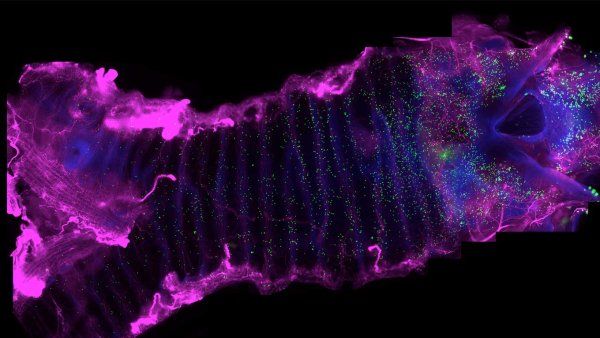

Alzheimer’s disease is defined by two protein deposits that are found in the brain: amyloid plaques and tau tangles. Aducanumab targets the plaques. It’s what’s called a monoclonal antibody, which works like the antibodies made by the immune system: It attacks amyloid plaques as if they were a virus or other foreign entity. Aducanumab is the first Alzheimer’s drug that is very effective at clearing these plaques.

How did the drug become controversial?

In February 2019, the manufacturer, Biogen, suddenly announced that they had stopped the phase III trials of aducanumab, which were designed to test whether the drug slowed cognitive decline for patients with amyloid plaques who were in the early stages of memory loss. Basically, Biogen’s statisticians had determined that there was a very low likelihood that the drug would show a difference in clinical outcomes compared with a placebo.

Then, eight months later, the company made another sudden announcement: As more of the trial data had become available, they had found that one of the trials – in which more people received the highest dose of the drug – actually was successful. In the following months, Biogen worked closely with the FDA to try to understand these very complicated data. There are now allegations that this relationship was a little too close; at least two congressional committees and the Office of the Inspector General are investigating.

What happened next?

On June 7, 2021, the FDA introduced yet another twist in the story: It approved aducanumab, against the advice of its own advisory committee. The agency did this through an accelerated path designed to increase the availability of new drugs for severe diseases that have very limited therapeutic options. In accelerated approval, you can approve a drug based not on evidence that it has clinical benefits – which is the standard for most drugs – but rather based on evidence that it changes the biology of a disease in a way that is likely to have clinical benefits.

So in the case of aducanumab, the phase III trials consistently showed that the drug removes plaques effectively – a 55% to 60% reduction, on average. There is a lot of controversy about whether removing amyloid plaques really benefits patients. It’s not a cure by any means. But based on the trial data for aducanumab and early results from two similar plaque-busting antibodies, my opinion is that these drugs do have a modest effect on slowing cognitive decline.

Other experts disagree with you, including some of your own UCSF colleagues who are not convinced there is enough evidence that aducanumab can help people.

I agree that this is not a home-run drug, I agree that the data could be clearer, and I can understand physicians who are worried and reluctant. I wish the FDA had required Biogen to complete a third phase III trial with the higher dose so that there wouldn’t be any confusion about whether the drug does or doesn’t work.

That being said, I’m not ready to throw this drug out entirely now that the FDA has approved it. Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating illness. Given the choice between the certainty of decline and the chance that a drug like this might slow that process – even if the benefit is modest, and there is risk involved – many patients will choose to take that risk. I feel we have an obligation to discuss this drug as an option with our patients who might benefit.

Who might benefit?

Patients who are in an early stage of Alzheimer’s – what’s called mild cognitive impairment. Based on what we know about the disease, it is unlikely that people who are in more advanced stages of Alzheimer’s are going to benefit. Physicians also should verify that patients have amyloid plaques before starting this treatment. It’s not enough to have the clinical symptoms; you want to have evidence of the molecular changes in the brain that define Alzheimer’s disease.

How are amyloid plaques detected?

The most accurate tests are amyloid PET scans, which can image the plaques in the brain. Unfortunately, these scans are very costly and not very accessible. But there are also spinal fluid tests that are more affordable and highly accurate. And soon, we may have reliable blood tests, which would greatly increase the cost effectiveness of and access to testing.

What are the drug’s side effects?

Mainly swelling or bleeding in the brain. This sounds really scary, but the swelling is reversible, and the bleeds are tiny – what we call microbleeds. In the trials, fewer than 1% of people treated with aducanumab had what we would consider very severe symptoms, including seizures or stroke-like episodes. Most participants who experienced swelling or bleeding had no symptoms or only mild ones, like dizziness or a little more confusion.

These side effects are more serious than with other Alzheimer’s drugs, but they can be managed. They resolve when patients stop taking aducanumab, and in most instances, patients can safely restart the drug later. However, people who are on blood thinners or who otherwise might be prone to bleeding should avoid taking aducanumab altogether.

Are you concerned about the cost?

Biogen has set the wholesale price for aducanumab at $56,000 a year. That’s way too high. Even if the drug is covered by Medicare, patients might still be liable for up to 20% in copays. A lot of people won’t be able to afford that. There is huge concern that this will exacerbate the racial and socioeconomic disparities that already exist in access to dementia care. I think the solution is for companies to price these drugs more reasonably and offer robust patient-assistance programs so no one is denied treatment because they can’t afford it.

How will aducanumab impact the future of Alzheimer’s care?

I think it’s going to herald a new era in Alzheimer’s therapy. There are now two other monoclonal antibodies for treating Alzheimer’s – lecanemab and donanemab – that are showing similar promise in early studies. In the next two to three years, as more clinical-trial results are published, a lot of the controversy and smoke around these drugs should clear. We will have a clearer picture of what these drugs do, who they help, and who they don’t help.

Consider the history of treatment for HIV and many cancers. The first drugs that were used to treat these diseases had serious toxicity and modest benefit – a lot like aducanumab. Yet we now have highly effective drug cocktails that allow people with HIV to live normal lives and keep the virus under control, and we have extremely sophisticated ways of understanding individual tumors and developing targeted therapies to treat them. With Alzheimer’s, we have just reached the precipice of this precision approach to treatment, and aducanumab is the first drug, hopefully, of many.

I wish it were a better drug. I wish it were less controversial. But I do think it’s a step in the right direction.

Disclosures: UCSF served as an enrollment site for the clinical trials of aducanumab. Gil Rabinovici was not involved in the trials. He has done consulting work unrelated to aducanumab for Eisai Co. Ltd., which has a partnership with Biogen Inc. to develop and commercialize aducanumab and other treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.